Last month, we went through some of the decision processes our ancestors went through to make the great trek to America. One of the most important parts of our family history is to understand why our grandparents left their home and everyone they knew and came across the ocean to a place that was entirely different.

Most of the Italians who came to America did not leave Italian farm work for American farm work. This is especially true if they were heading for Chicago. Leaving one farm for another didn’t make sense. They barely had enough money to get aboard ship. How could they buy land in America? The feudal system of working land for its owner was not really set up the same way in America, so, what to do?

Many of our ancestors decided to come here after receiving letters from friends and relatives who were already here. These letters persuaded your ancestors that there was good money to be made here, and it was a lot less backbreaking than farming! Many of them had to work in factories, and the work might be difficult, but all the uncertainty of farming (crop failure, blight, temperature) was eliminated. All that toil would automatically pay off in a steady paycheck.

So our ancestor had to book passage on a ship leaving one of the major Italian ports, usually Palermo, Naples or Genoa, but there were others, too. This was after saving money for months, maybe even years. In some cases, they booked passage but did not make it to the port in time, and literally missed the boat! We’ll talk about them later.

Now, our ancestor gets on board the ship and has to go through a medical examination. Why? Many of us know that the immigrants who passed through Ellis Island had to go through an often-embarrassing medical exam, so why did they have to go through one just to board ship? Well, if a passenger was found to be ill and was designated by Ellis Island to return to Italy, the steamship company had to pay the passage back home, PLUS a fine of $100, PLUS they lost more cargo space they could have filled with, well, cargo! So they checked people out as they boarded ship so there would be less chance of illness. And, let’s face facts, if one guy got tuberculosis as he boarded ship, a bunch of people had it by the end of the voyage. That could cost the ship company a pretty penny!

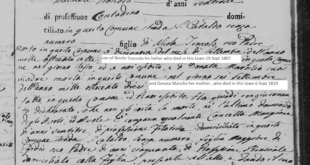

As they boarded ship, they had to answer a bunch of questions. These answers were filled out on the passenger manifest (also known as passenger list). After they got through the Ellis Island process, they had to answer these questions again for the officials, presumably to make sure they had the same story!

One problem was that the passenger who got on board ship with $30 might get off with $10, or nothing at all. Theft on the ship was common, and these bored passengers would frequently gamble on cards, or whatever else they could, and people ended up with nothing. If they had no money, they had to arrange for money to be sent to them in order to reach their final destination. Otherwise, they would be tagged as “LCP” a Likely Public Charge.

So after two to three weeks of bad food, smelly conditions, poor facilities, seasickness and other unpleasantness, they arrived at the port. Usually this was New York, but many people also went to Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and even Galveston or New Orleans if they were heading south. Why did they choose ports other than New York? Mostly because it was a couple of dollars cheaper.

At Ellis Island, they were sent up a set of stairs carrying the possessions on their back. They watched for people who had trouble making it up the stairs and wrote chalk marks on their clothes that they needed to be examined for health problems. Everyone had to have a very quick basic medical checkup. I think in the Army it was called a “short-arm inspection.” They also checked the eyes for a disease called traucoma. They flipped the eyelids up to look at them, which was painful. If they found any health problems, they put more chalk marks on the clothes and sent them off for further inspection.

Sometimes they would tag someone as having suspected mental problems. Typically, if someone was too happy in line, they figured they must be crazy! These people had to take a literacy test to make sure they were not “feeble minded.” (This was the 1910s, folks. No political correctness back then!)

The best thing was to get through all those tests without any chalk marks. Some folks wore their coat inside out, got all marked up with chalk, and then turned the coat back the right way so they would get through the line! Pretty clever, huh?

Now they get to the Ellis Island officials who would ask them questions to determine their fitness to stay in the country. This has been likened as the nearest earthly likeness to the Final Day of Judgment. Other than the money question, the answers should not have changed. It was important for our ancestors to be careful when answering the questions about employment. If they ask you “Do you have a job waiting for you in this country?”, it would SEEM to make sense to say “Why yes! I have a job lined up and I will not be a burden on my new land!” However, the reality was very different. It was viewed that if you had already lined up a job ahead of time, it was viewed as indentured servitude. Many people, especially earlier immigrants from the 1800s, traded most of their salaries for payment of their passage. They did not want this to continue. So it was in your best interest to say “No sir, I do not have a job but I am eager to learn and willing to work.” Sounds like a job interview, doesn’t it?

So they answer the questions, and were sent out of Ellis Island to board trains to leave for their final destinations. About 2 percent of those who left Europe were sent back. The goal was always to admit rather than reject.

A hundred years later, we can go on-line and see a copy of the passenger manifest that was filled out with our ancestor’s name on it. Next month, we will talk about how to find that manifest and what we can learn from it.

Write to Dan at italianroots@comcast.net and please put “Fra Noi” in the subject line.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian