Franco entered the barn to gather the cows and lead them out to graze. A few chickens followed him clucking and prancing at his feet. The 14-year-old boy gave three crisp, high-pitched whistles announcing his presence to the cows, which rustled in their stalls, turning their heads toward the piercing noise. They had been milked three hours ago and knew it was time to go outside.

“Good morning cows! A new day is here. More fresh grass to eat and milk to give. You have me today so be on your best behavior!”

Franco unlatched them one by one from the chain harnesses that secured them to their enclosures. More chickens entered the barn to check on the commotion. As he went from stall to stall, he called the cows by their given names, talking to them as if they understood. Even unchained, the cows stood in place. When he had finished untethering the last one, he hastened them out of the barn with a slap to their backsides. Noticing their stalls needed cleaning, he made a mental note to let his mother know so that one of his brothers or sisters could accomplish the chore, ensuring the cows would enjoy clean bedding when they returned.

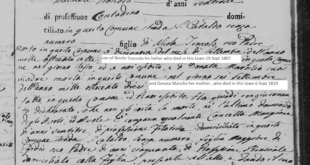

Normally Franco’s younger brother would be responsible for taking the cows to pasture while Franco worked as an apprentice at the family’s carpentry shop in town, but today was different. Their father was ill in bed and the shop was closed, so Franco volunteered to watch the cows, relieving his overjoyed brother of his duties for at least a day.

Franco shooed the chickens out of the barn with much fracas, then closed and latched the large, wooden doors. Meanwhile, the cows hovered outside the barn, whipping their tails in all directions to swat swarms of flies from their bodies. The pests were everywhere, even at this early hour, owing to the intense heat that had plagued the area for the past two weeks. The townspeople couldn’t remember a hotter streak of June days. Franco looked up at the early morning sun, shading his eyes with his hand, before leading the cows to the water basin, a few paces from the barn, allowing them to drink their fill. The sweat was already forming on his brow and under his arms. He knew it was going to be another sweltering day, and he decided to direct his small herd high up the mountainside where there was a meadow shaded by tall pine trees. There, the cows would be better protected from the sun’s punishing rays.

Franco was the fourth of six children, all of whom lived with their parents in a small, two-story farmhouse that shared a common wall with the barn. Their modest home was perched on a plateau at the bottom of a tall mountain and at the edge of a ravine that led to a river in the Apennine range in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. The first floor did triple duty as a kitchen, dining room and gathering place where the family read, chatted, played card games, and tried to stay warm at night. Made of stone, the uninsulated house did little to repel the mountain wind and cold. The cooking was done in a stone hearth, with all the available pots, pans, and utensils hooked on a heavy, oaken ledge above it. A potbelly stove in a corner of the kitchen served as an additional heat source. Without natural gas or electricity, firewood was the sole source of energy, and it was in constant demand. Trees were regularly cut down and their trunks and limbs chopped to fit the fireplace and stove. This precious resource was stored under a tarp along the wall outside the front door. Part of the daily routine was to retrieve firewood from the stash and pile them in a holding area in the house’s foyer.

The family bedrooms were located upstairs. They were small, with low ceilings, and barely fit a bed and dresser. To cope with freezing winter nights, the family built and used a sled-like wooden device that was slipped between sheets and quilt arching. Suspended within the vaulted framework was an iron container filled with embers and ash that warmed the bedding while preventing it from catching fire. The apparatus was pulled out from under the covers when the family was set to retire, swaddling the family in warmth when several inches of ice caked the bedroom windows and the cold north wind howled outside. The device was nicknamed “the priest” by the town pastor and elders while they were drinking wine and playing cards late one night at the town’s bar. The moniker was based on the happy assumption that priests warm the souls of their parishioners during the homily on Sunday and the contraption did the same to their bodies in the evenings.

While the family slept warm and secure in their “blessed” beds oblivious to the scratching sounds above their heads. The house shared a roof and attic with the barn, and the hay was stored above the cows’ stalls. Mice searching for food in the area would range the length of the attic, foraging and playing, but the family paid their tiny noises no mind. But woe betide the rodents that wandered into the living area, where the family cats were at the ready.

The barn doubled as a bathroom. Toilet paper was a luxury, so book and magazine pages were used, supplemented by large plant leaves when available. Water for drinking, bathing, and cooking was collected from an underground stream that had been tapped with an iron rod tube driven deep into the rock. The source was a good distance from the house, and family members alternated fetching the water. Back and forth they would walk along a well-traveled path to bring home two full buckets hanging from the notched ends of a large branch carried on their shoulders.

With cows well-watered, Franco began the three-hour trek up the mountainside with his small herd in tow. He carried a walking stick for support and balance as he negotiated the tight mountain paths, and on his back he wore a cloth sack that held his food and other items. As he drove the herd upward, he allowed them to graze from time to time along the way until reaching their destination, a green pasture on a spacious plateau located just before the solid rock mountainside shot upward toward the peak. Franco would let the cows eat there for a couple of hours before returning down the mountainside to the farm.

An unrelenting midday sun beat down as the cows settled in and began to peacefully feed. Walking toward the shade of a big fir tree, Franco found a large boulder to use as a backrest, sliding down its face and preparing to have his lunch. He first placed his walking stick and cloth sack to his side, glanced toward the cows to ensure they were still in sight and safe. Once satisfied, he reached into his sack to retrieve the food his mother had packed. Franco unwrapped the cloth that protected a piece of homemade bread and a lump of cheese, then tore off a hunk of bread, pared a slice of cheese with his pocketknife and started eating. Grabbing his canteen, he gulped the still-cold water to move the food further down, then took another swig before wiping the beads of sweat from his forehead with his sleeve. He checked the cows again and saw that they were still enjoying the lush, pasture grass.

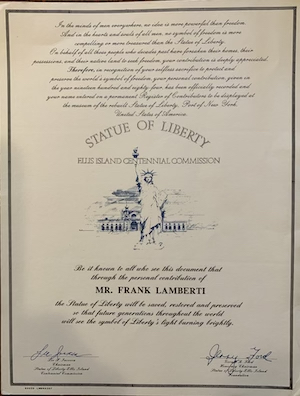

Franco loved being alone high in the mountains, listening to the cowbells with their different pitches and tones. Viewing all the wonders of this small domain and feeling full of confidence, he considered himself a man and very much in command, even though he was only 14. After finishing his lunch, he neatly folded the cloth, stuffed it back in the sack and retrieved his journal. He opened it to a spot held by pencil and reviewed his half-finished sketch of the Statue of Liberty, which he was copying from a photo from a magazine his sister had sent. She had immigrated to America and regularly wrote the family long letters, parceled along with magazines, telling them about the abundant job prospects and bright future awaiting her children: Opportunities that were nonexistent in a small, mountain farming town in the Apennines.

Franco loved being alone high in the mountains, listening to the cowbells with their different pitches and tones. Viewing all the wonders of this small domain and feeling full of confidence, he considered himself a man and very much in command, even though he was only 14. After finishing his lunch, he neatly folded the cloth, stuffed it back in the sack and retrieved his journal. He opened it to a spot held by pencil and reviewed his half-finished sketch of the Statue of Liberty, which he was copying from a photo from a magazine his sister had sent. She had immigrated to America and regularly wrote the family long letters, parceled along with magazines, telling them about the abundant job prospects and bright future awaiting her children: Opportunities that were nonexistent in a small, mountain farming town in the Apennines.

Franco pulled his favorite American magazine from the sack and opened it. Pressing it flat with the palm of his hand and skimming it, he stopped momentarily to stare at a picture of a man in an odd uniform with the number 3 on it. Wearing an impossibly small cap and pants that stopped at the knee, the man was leaning on a sculpted stick with a knob at the end. Continuing to flip through the pages, he laughed at a photo of a comical little man sporting a small mustache and bowtie, with a cane resting in his elbow joint. But he came to a full stop when he got to the section displaying his favorite photos. There, he marveled at the vast landscapes of a country that Franco could only imagine. After spending a good amount of time viewing these panoramic scenes, Franco continued flipping until he arrived at a two-page spread of the Statue of Liberty — the symbol of America. As the cow’s continued to graze, Franco folded the magazine over, took the pencil in his right hand and continued with his drawing. He often dreamed of living and raising a family in America. He had heard of the nation’s promise from many people. Working on his sketch somehow brought him closer to that dream.

With the bells chiming a lullaby and the sun’s warmth cradling him, Franco fell into a trance that morphed into sleep. Awaken by a weight that moved across his legs at his ankles, he looked down just as a viper was slithering off him. Instinctively, he shot his legs upward to throw the snake to the side before standing up. With a familiar hissing sound, the startled reptile turned and struck Franco, its venomous fangs striking the toe of his left shoe. Franco calmly moved his right leg into position and crushed the head of the serpent. He then bent down to grab his stick, centered the dead snake on its tip, and slung it deep into the woods where the wild boars would eat it. Meanwhile, his small herd was feasting on grass, oblivious to the ruckus. When he arrived home and the cows were safely back in the barn, he didn’t tell anyone of his encounter with the dangerous viper. When his mother and brother asked how the day went, he simply said, “fine.” In the big picture, it was a danger presented itself, he took care of it, and he and the cows were safe.

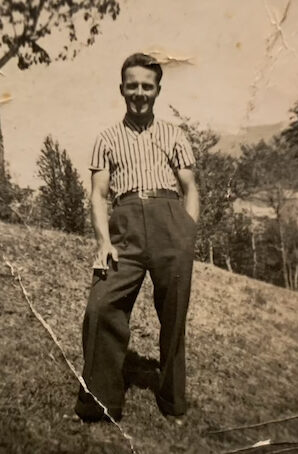

Decades later, I listened as my father recounted the story of his boyhood run-in with a deadly serpent during a lunch break at Cherry Electrical Corp. He was 53 and working as a carpenter for the company and I had recently graduated from college and accepted a sales position at the company.

My father’s American dream was finally realized in 1955, when he was 35. He worked for five years as a carpenter building houses as the suburbs of Chicago spread across the metropolitan area. But the region’s fickle weather caused work stoppages and lower pay, which sent him in search of a job with a reliable paycheck. That search led him to Cherry Electrical.

I enjoyed his stories about his youth in Italy immensely, but he rarely had the chance to share them when I was a boy because he had to work multiple jobs to pay back debts incurred during our immigrant while staying even with the family’s expenses. When we worked at the same company, the stories would flow, and I was glad for that. The viper incident had happened 39 years earlier and yet this was the first I was hearing of it. I sat in wonderment as he explained how the top of his left shoe, previously brown, had turned black at the site of the snake’s poisonous bite. “I was startled, I just went into action,” he recounted with a slight laugh. “It was something. My mother never asked me why one shoe toe was black and the other brown,” he shared before falling silent as if recalling that day.

In the two years we worked together, we would often sit in my father’s workshop and have lunch. His new domain was located at the rear of a large warehouse on the second floor of the factory, above the main manufacturing level, affording him a bird’s-eye view of the outdoors through large-paned windows. He didn’t care that his space was remote. He liked to work and sit alone, and he preferred to be away from the main traffic. He told me he felt in control up there, just like he did when he led the family cows high up the mountain. His shop was stocked with all the tools of his trade and anchored by a sturdy, four-legged workbench he had built. A lattice rack that hung to the side of the bench was home to bins of nails, nuts, and bolts, with excess pieces of wood of all shapes and sizes stored in large barrels that stood in one corner. Pinned next to his work orders on his corkboard was a ratty, crumpled sheet of lined paper that look like it had been torn from a journal and held close for decades. As I stared at the sketch during our lunch break on my first day on the job, he told me it was his rendition of the Statue of Liberty, drawn when he was 14 years old.

World War II interrupted my father’s youth, and he married two years after it ended and soon started a family. There was much to rebuild in Italy and the reconstruction period brought heaviness and hardship. He worked alone as the town carpenter back then; his father having passed away. Though work was plentiful, pay was intermittent, strengthening his resolve to emigrate to America. A week before my father died, he told me as we sat on his front porch that he considered America to be his true home, having spent 53 of his 88 years in his adopted town of Highwood, Illinois. He expressed no regrets. For my father, it was all about duty to his family. “We were ready to begin a new life in a new world,” he told me, “starting with nothing, without knowing the language, with many debts, but with so much hope and determination.”

World War II interrupted my father’s youth, and he married two years after it ended and soon started a family. There was much to rebuild in Italy and the reconstruction period brought heaviness and hardship. He worked alone as the town carpenter back then; his father having passed away. Though work was plentiful, pay was intermittent, strengthening his resolve to emigrate to America. A week before my father died, he told me as we sat on his front porch that he considered America to be his true home, having spent 53 of his 88 years in his adopted town of Highwood, Illinois. He expressed no regrets. For my father, it was all about duty to his family. “We were ready to begin a new life in a new world,” he told me, “starting with nothing, without knowing the language, with many debts, but with so much hope and determination.”

My father was sitting in his favorite living room chair on Nov. 5, 2008, looking out of the picture window and marveling at the many different-colored birds that visited the birdhouses in his apple tree, when he leaned to his left and died. Weeks later, going through his keepsakes, I once again saw his hand-drawn picture of the Statue of Liberty. I carefully removed the faded yellow tape on its corners. For the first time, I turned it over and found another sketch, a smaller version of the Statue of Liberty, with four figures standing at its base. Above the liberty flame there was a caption that read: “My family in America.” It was dated 1934 and signed by my then 14-year-old father, Franco Lamberti.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Beautifully written. I so enjoyed this article from Mr. Lamberti. He helped me to feel and appreciate the post-war agricultural lifestyle in his town, and I followed with true fear with the serpent crawling over a napping Franco’s ankles. The drawing of the Statur of Liberty seen years later brought the story a valuable constructive element.

I hope Mr. Lamberti continues to write in retirement. I will be looking for his stories in future editions of Fra Noi.

My Aunt Lena was married to a Primo Lamberti. I don’t know if he was related. I loved Primo. He was a big happy man, always laughing and loved to eat and cook. He passed away way too young.