Even though only 25 percent of my DNA leads back to Italy, I have always considered myself Italian. Given my surname, everyone assumes I’m pure Italian. (Everyone except my Irish mother who always reminded me that the majority of my roots lay in Ireland.) The fact that I grew up in a part of Illinois inhabited by few Italians did nothing to separate me from my heritage. Whatever everyone else was, I was Italian!

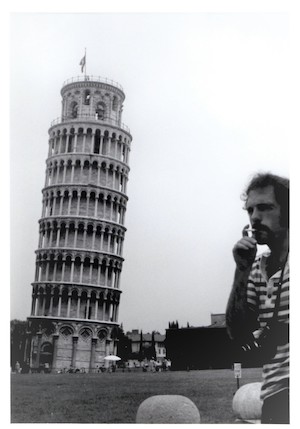

On my first trip to Europe when I was 23, I discovered I felt more comfortable in Florence than in any other city I had visited or in which I had lived. I decided that, someday, Florence would become my home. Everyone who knows me well knows I’m interested in anything Florentine.

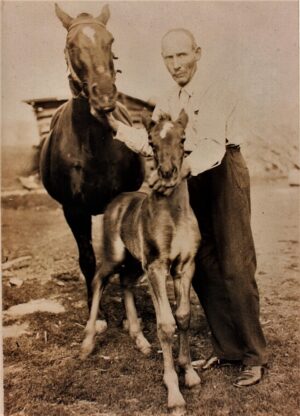

Last May, my sister texted me about a CBS program on Florence she thought I would want to see. The show was fascinating as a whole, and one small part turned out to be life-changing. In it, there was a very brief discussion of Jure Sanguinis, the right of Italian citizenship by bloodline. I was thrilled to learn there was a chance I could actually obtain Italian citizenship while continuing to retain my U.S. citizenship. I had no idea how consuming the process would become and how I would end up connecting with ancestors I never had the opportunity to meet. I learned, for example, that my great-grandfather most likely made a living divining the fortunes of his paesani by “reading” the entrails of songbirds.

I knew why I wanted Italian citizenship; it was simply pride in my heritage. In getting to know other people online who had applied for citizenship recognition or who were in the process of applying, I discovered that many have the same motivation. But there are other reasons for having one’s Italian citizenship recognized. Once a person obtains Italian citizenship, he or she is considered a citizen of the European Union and is afforded all the benefits of that designation. If you have dreams of living in Europe, being a citizen of Italy makes those dreams a possibility. There’s no need to apply for a special visa to stay more than 90 days; obtaining employment and owning property is much easier; and European health care is extremely good and, because of government subsidies, much more affordable than in the United States.

If you don’t want to live in Europe but do visit, carrying a passport from any EU country cuts your wait time at each border, in some cases by up to an hour. Although this is a trivial reason to go through all the work required to have your Italian citizenship recognized, it can be a real time-saver for someone who travels to Europe often. For some, helping to shape the destiny of their ancestral homeland through voting is important. As an Italian citizen living abroad, a person obtaining citizenship through Juris Sanguinis is allowed limited voting rights.

It’s important to note that Juris Sanguinis doesn’t grant you citizenship; it recognizes citizenship you’ve had since birth, in most cases without realizing it. You aren’t becoming an Italian citizen; you’re being formally recognized as such by the Italian government.

The steps that lead to having your Italian citizenship recognized are simple enough in concept but can be quite time-consuming. Once you determine you qualify, you must collect the documents proving your claim to citizenship and present them to the local Italian Consulate. Then you have to wait for the notice that your citizenship has been recognized: a wait that can, in some cases, take up to two years.

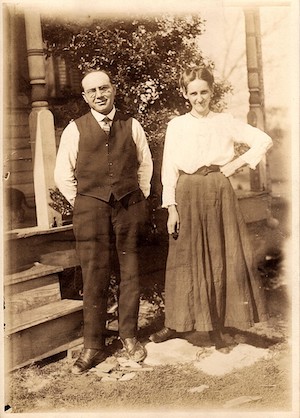

Italian law states that anyone of Italian descent is an Italian citizen so long as no one in their ancestral line renounced their citizenship before the next person in that line was born. (My great-grandfather Domenico Rossi was still an Italian citizen when my grandfather Dominick was born.) Of course, like most things, that requirement sounds much simpler than it really is. In the first place, Italy didn’t become a country until March 17, 1861. No one who died before that date was an Italian citizen, so they couldn’t pass citizenship on to the next generation. This doesn’t apply to many people who are claiming their Italian citizenship in the United States since the great migration of Italians to this country didn’t peak until well after that.

Prior to 1992, Italian law required anyone who obtained citizenship in another country to give up their Italian citizenship. As such, many people lost their right to Italian citizenship because their ancestor from Italy naturalized in this country before the next person in their line was born. In very rare cases, people renounced their Italian citizenship for other reasons, but naturalization was the main reason most ties were severed.

It’s important to note that, before 1948, women lost their Italian citizenship when their husband naturalized. To successfully claim citizenship through a female ancestor in this case, you have to argue in an Italian court that the line remains intact through the wife since she didn’t actually renounce her citizenship. This is a much more complicated and expensive process, requiring people to hire attorneys to make their case in Italy.

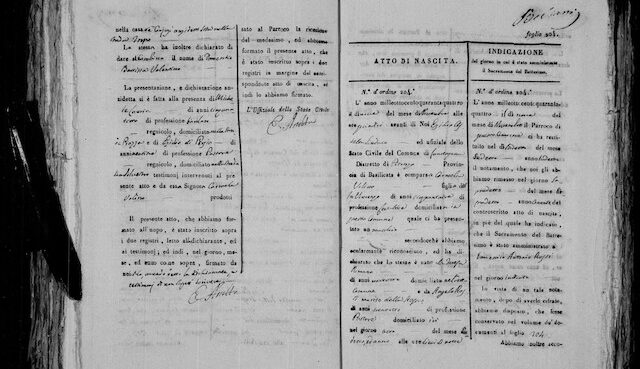

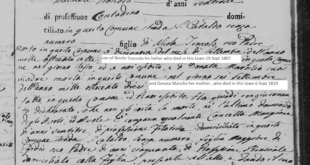

If you feel you might qualify for citizenship through Juris Sanguinis, a lot of work is required to collect the documents to prove it. To begin your quest, you will need to hunt down the birth, marriage and death records of your Italian ancestor who came to this country and through whom you are claiming citizenship. For some, these are the most difficult records to obtain since many of us don’t know exactly where our ancestors were born. If you know, you’re ahead of the game. But if you think you know based on vague family stories, you may find yourself spending time pursuing dead ends. Family stories had my great-grandparents’ birthplace in Genoa, but when I was unsuccessful finding records there, I talked to a family member who had her DNA traced to Laurenzana, on the other end of the peninsula. A quick search there turned up the birth and marriage records I needed.

Familysearch.com, a free record-search portal run by the Church of Latter Day Saints, is a great way to begin to track your family history. Ancestry.com provides even more information for the price of a subscription. If you want to keep costs down — and who doesn’t? — many libraries pay for a subscription to Ancestry.com for their patrons.

Once you’ve found the comune where your ancestor was born and married, a simple letter to that comune’s vital records department requesting an extract, or “Estratto,” of the birth and marriage records will usually produce the documents you need. When sending the request, keep in mind Italians generally speak Italian — that is to say, you shouldn’t assume the person reading your letter speaks English. Even if you use a free translation service such as Google Translate, the courteous thing to do is send the letter in the native tongue of the recipient.

It’s really simple to find the address of the comune you will need to contact. A list of the almost 8,000 comuni in Italy can be found at Comuni-italiani.it. If you know the province the comune is in, just click on that province to find a list of all the comuni located there. You’ll be able to enjoy other interesting information about the region as well. Although it’s not usually necessary, some people suggest including 5-10 euro to cover postage and a self-addressed envelope along with your request. Another option is to get international postage from the U.S. Postal Service and include it on the self-addressed envelope.

If you don’t have the naturalization information for your Italian ancestor — and most people don’t — you will have to ask the National Archives and Records Administration to perform a search to prove the naturalization didn’t occur before the next generation in your line to Italian citizenship was born. Before the early 1900s, naturalization was done in local courts, so many of these forms will be found at the state or local level.

If you know your family’s history, U.S. documents can be easier to find. Contact the state or municipality in which your ancestors were born and died to request their birth certificates, marriage application, marriage license and death certificates. If available, the long form of each record, which indicates the names of that person’s parents, is required. Some states and municipalities are very slow to process such requests. St. Louis took more than three months to produce my father’s birth certificate, but I was able to obtain it in a matter of days using a commercial service called Vital Check. Of course, I paid an additional fee for their efforts.

Many births in the 1800s were not recorded, and this is especially true for births among immigrants. If you are unable to locate a birth certificate, the next best thing is a baptismal record from a church. If using church records, it will be necessary to obtain a notarized letter from an official at the church attesting that it is an accurate record from their files.

When requesting these records, it often doesn’t cost much more to order a second copy. This is a good practice since it’s possible a document can be misplaced at some point in the process. In addition, all the documents you provide to the consulate are kept by the consulate. Having a second copy may also come in handy in the future, particularly if another family member decides to claim their citizenship.

Of course, if you are like most people applying for citizenship recognition, you will come to points where you need assistance. Fortunately, it’s easy to find at no cost. One great resource is the Facebook group “Dual U.S.-Italian Citizenship.” It’s a community of more than 20,000 members who are either going through the process or have already completed it. This forum’s sole purpose is to help and encourage others who are claiming their Italian citizenship. It can be instrumental in helping find many elusive documents without charge.

It’s important to make a copy of each document you receive so you can send it out for translation. If you don’t know of a translation service, the website Fivver has many, some of which specialize in translating for people claiming Italian citizenship. Since the cost of translation varies greatly, doing a little research can save you a lot of money. Most consulates don’t require “certified” translations, but the translations must be completely accurate. If you are fluent in Italian, you can translate the documents yourself.

“Apostille” is a term we don’t hear very often. It’s a special certification that authenticates documents in the eyes of the member nations of the Hague Apostille Convention. Most U.S. documents provided by states and municipalities that are destined for use in an international context require this certification. This is done by the office of the Secretary of State wherever the documents are produced. It’s usually very inexpensive, just $2 for each document in Illinois if it’s done directly with the Secretary of State’s office. In Missouri, the cost is $10 for each document. However, there are many services that will do the procedure for you for $75 or more per document.

Once your documents are within striking distance of being collected, you need to schedule an appointment at the Italian Consulate. There are 10 Italian consulates, including the consular office in the U.S. Embassy in Washington, D.C., but you must make an appointment at the consulate that is responsible for the area in which you live. Appointments can only be made online, and obtaining one can, in itself, be a time-consuming exercise. Some consulates are not setting appointments right now due to the pandemic or are setting only virtual appointments.

The first step in obtaining an appointment is setting up an online account at the website of the Italian Consulate. This process is free and requires only basic information along with some form of government ID, like a driver’s license or passport. It may be helpful to set up two separate accounts in case the one you initially make is either too soon or too far down the road.

Each consulate sets its own appointments, and most are booked months or years in advance. Currently, the Chicago consulate is booked two years out. Each weekday when it’s midnight in Rome, new appointments are released and almost immediately claimed by people glued to their computers and ready to pounce. Even though you have to be really lucky to get an appointment when they are released, don’t get frustrated. Many people cancel their appointments or fail to confirm them, prompting the consulate to re-release them, often only days before the appointment date. I found that by logging into the website many times a day, I was able to secure an appointment just far enough out that I could have my documents ready with only a bit of a scramble. Persistence and patience are the watchwords to get an appointment that works for you.

One of the big questions most people ask is: “How much does all this cost?” Unfortunately, it’s impossible to answer given how greatly individual circumstances vary. The only consistent cost is the fee for the consulate appointment, and even that varies due to fluctuation in the value of the dollar relative to the euro. The consulate fee is 300 euro paid in equivalent dollars adjusted quarterly. For the first quarter of 2021, that’s $357.30.

Other than the consulate fee, there are costs for obtaining certified documents and having the documents apostilled and translated into Italian. A complete list of the documents required is available on the Italian consulates’ websites. Many factors impact the total cost of the process. Obviously, the fewer generations for which you have to obtain documents, the lower the total cost will be. The cost of translation can vary widely. Some people pay as little as $5-10 a page, while others are charged as much as $65 a page.

In addition to saving quite a lot of money, doing the research yourself makes the entire experience much more personal and affords you the opportunity to learn about your ancestors’ incredible journey. For those who lack the time and have the money, service providers offer to do much of the work for you, with a complete package ranging from $1,500 to more than $10,000. While most are reliable and will save you some effort, the popularity of dual citizenship has spawned a breed of “service providers” who do little to earn their fees. If you hire someone to help you, make sure you get verifiable references. Some providers have been accused of setting up multiple email accounts and assuming different identities to give themselves glowing references.

If you have been careful in collecting your documents, your consulate appointment, while stressful, can feel anticlimactic. You simply present documents proving your identity, such as a driver’s license and passport (including a copy for the consulate to keep), and the documents you have collected to prove your Italian citizenship. A consular official looks at them to make sure they appear to support your claim and, if they do, collects the fee and sends you on your way.

Once your documents have been approved at the consulate appointment, your wait begins while your request for recognition wends its way through several layers of bureaucracy. It can take anywhere from five months to two years following your citizenship appointment before you receive notification that you are officially a citizen of Italy. I’m in that long wait now, made even longer by slowdowns and shutdowns caused by the pandemic. It’s been a little more than a year, and I anxiously check my email each day to see whether, by some miracle, my recognition has arrived.

The above appears in the March 2021 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Curious how long getting citizenship via Jure Sanguinis took and if it was obtained? Applied to Chicago consulate in April of 2021 and still haven’t heard – now 28 months. Thank you.