Badly wounded in the early days of the War in the Pacific, Neil Iovino nevertheless survived the Bataan Death March and 44 months in jungle prison camps.

The youngest of eight children, Neil Philip Iovino was born on the West Side of Chicago on Jan. 3, 1918. His parents, Domenico and Richetta Serpico Iovino, came to Chicago from Scisciano, near Naples.

A graduate of Notre Dame Grammar School on Flournoy Street, he attended only one year of high school, but my dad was street smart. When people asked him where he went to school, he would say Notre Dame and they often thought he went to Notre Dame University.

His early life was marked by tragedy. His family lost their home during the Depression, and both of his parents died of strokes while he was a teen. Living with one or another of his two married sisters, he worked at whatever jobs he could find, including delivering telegraphs, shelling pecans, helping his brother-in-law sell produce and cutting out rain capes from sheets of processed rubber.

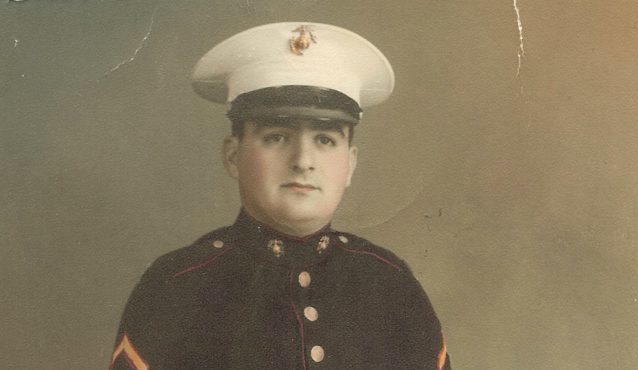

When he was 21, he saw a Marine recruitment poster touting “Education, Adventure, Travel” and enlisted on Dec. 7, 1939.

After boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego, he volunteered for duty in Shanghai, China, and became a member of the Fourth Marines, who protected the 25,000 Americans living in the American sector. His duties in Shanghai included chauffeuring and interpreting Italian when needed.

He was stationed in Shanghai from May 1, 1940, to Nov. 28, 1941, when President Roosevelt ordered the Marines to evacuate all Americans living there to the United States. The Fourth Marines were then sent to defend the Subic Bay Naval Base adjacent to the city of Olongapo in the Philippines.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Subic Bay was under constant aerial bombardment, and my dad was the first to be wounded. Struck in the abdomen by several pieces of shrapnel, he was in critical condition when he was brought to the Riverside Cabaret, which had been converted into a hospital, where an emergency appendectomy saved his life.

While he was recuperating, the Japanese Army attacked the Philippines, overwhelming the American forces and forcing their surrender on April 9, 1941. What followed was the infamous Bataan Death March, during which 66,000 Filipinos and 10,000 Americans were forced to slog more than 60 miles through dense jungle and stifling heat by Japanese captors who killed any prisoner who lagged behind or paused to help a fallen comrade. Six days later, at least 2,500 Filipinos and 500 Americans were dead, and the remainder were subjected to inhuman conditions and inconceivable brutality until the end of the war.

My dad’s buddies helped him the first 10 miles of the march, but because of his injuries he was sent with other seriously wounded prisoners to Bilibid Prison Camp in Manila. Only by the grace of God was he spared being killed on the march. A surgeon and fellow prisoner operated on him in the Bilibid Prison Camp, where he stayed for over a year.

Despite his weakened state, his work detail included heavy lifting, airfield construction and road repair. Throughout his ordeal, my dad was a morale builder, holding onto the belief that they would be rescued. He believed God would let him see his family again and enjoy another pasta meal.

My dad was then sent to the Cabanatuan prison camp, where he endured two more operations. Even the doctors marveled that he pulled through. Because of his injuries, the Japanese spared him harsher work details and conditions.

However, the lack of food and its contaminated quality caused beriberi, dysentery and palagra. The mosquitoes carried malaria, and the heat could be extreme. Only the sickest prisoners remained in Cabanatuan prison camp but were still expected to do work details.

Imprisonment at Cabanatuan ended up being a lucky break. In the dead of night, the Sixth Rangers of the U.S. Army, led by Col. Henry Mucci, and with the help of Filipino guerillas, made a surprise attack on the camp, killing the Japanese guards. After nearly four years in captivity, my dad and the other POWs returned to the United States as free men in 1945, where they were wined, dined and treated to ticker tape parades.

Among the medals he earned were the Silver Star, Bronze Star and Purple Heart Medal. A photo of him in the prison camp appeared in a story published in the February 1945 issue of LIFE magazine.

After a brief stay in three hospitals, my dad and other Marines were contacted by RKO Studios to promote the movie “Back to Bataan,” starring John Wayne and Anthony Quinn. The film features actual Bataan Death March survivors at the beginning and end. The last survivor shown at the end of the movie is my dad, marching to the song “California, Here I Come.”

RKO Studios engaged my dad and other Marine veterans featured in the movie as representatives. They went from town to town where the movie was being shown, also appearing at nearby defense plants to appeal for increased production of desperately needed war materiel.

At the conclusion of the RKO promotional tour, my dad made a large number of appearances on behalf of the war effort throughout Chicagoland, mainly to stimulate the sale of war bonds. During one of those appearances, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized, but his sisters checked him out of the hospital and cared for him at home.

He was honorably discharged as a gunnery sergeant from the Marines in 1946. Luckily for my dad, his sister Carmella had a best friend who lived across the street from the grade school that he attended. He and Laura Baldoni were introduced, they dated, and my dad proposed.

Because of his nervous breakdown, Laura needed my dad’s doctor’s permission to marry him in May 1949. Despite her family’s misgivings, Laura’s love, belief and faith in him resulted in 50 years of marriage, five children, four grandchildren, and one great-grandson that he was able to meet on Skype.

My parents lived for a while with his sister and her husband in Lake Bluff. He learned the printing trade under the G.I. Bill then went to work for the Waukegan News Sun, earning enough money to buy a small home in Knollwood.

They moved to Highland Park in 1954 and joined Immaculate Conception Parish. My dad worked the night shifts at the Chicago Tribune and then the Chicago Sun-Times. He also worked at the Highland Park Post Office and as a chauffeur for a corporate executive.

As children, we really didn’t understand what our father endured. When our father wore swimming trunks, we thought he had six belly buttons but learned those extra indentations were scars from shrapnel. His Marine Corps belt was used to discipline us. When we misbehaved, he would ask us, “The war made me crazy, what’s your excuse?”

There was always a lot of yelling in our house, and we just accepted it. We didn’t know how much was from being Italian and how much was a result of the prison camp experience. He could call us every name under the sun and then talk to us as if nothing had happened.

There was a lot of laughter, too, and our dad had a hearty, contagious laugh. He was very talkative and had to have the last word. He loved to walk and bicycle, and he was a good baseball player. At one Lake Forest Day carnival, he won so many prizes by knocking over dolls with baseballs, he was asked to stop playing.

There was always food in our house, particularly fresh fruits and vegetables. The biggest sin would be to have a party and run out of food so we always had more than enough when we had guests over.

He was a life-long member of several veteran organizations, including the American Legion Highland Park Post 145, Veterans of Foreign Wars Highland Park Post 4737, Disabled American Veterans, American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor, American Ex-Prisoners of War, Military Order of the Cooties, and Military Order of the Purple Heart. He volunteered at the VA and sold poppies in Highland Park. He gave talks about his war experience at schools and veteran memorials.

In 1967, he and Laura travelled to the Philippines to take part in a 25th anniversary reunion of the Bataan Death March. During that trip, they also visited Japan.

In 1995, he was invited to Taiwan to receive the Medal of Honor of the Vocational Assistance Commission for Retired Servicemen, Republic of China, “in recognition of his outstanding contribution as a veteran of World War II, in upholding international justice, safeguarding freedom and peace, promoting veterans’ welfare and strengthening mutual relations and cooperation between our two countries.”

His wife suffered from dementia for several years and in February 2000, he lost her to pancreatic cancer. When he lost his only son two years later, the family initially thought it was from a heart attack but the autopsy revealed that he had committed suicide. It was heartbreaking to see a person who believed in never giving up endure the loss of a loved one who died at his own hands.

For years on Tuesday mornings, my dad served coffee and pastries in his kitchen to friends from the local veteran groups of which he was a member. They were a blessing to him after the deaths of his wife and son.

After a brief stint in assisted living, he spent the last years of his life comfortably in his own home. He died at the age of 90 in 2008, after a tumble down six stairs in his home in Highland Park. At the time, he was wearing a white T-shirt similar to the one he had on in the movie “Back to Bataan.”

He taught his children: We are put in this world to help each other.

The above appears in the September 2018 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

I just finished watching Back to Bataan for the first time and saw the Bataan Death March survivors marching including Neil Iovino from Chicago. Since I’m from Central IL I did a quick search and was amazed and happy to see he had lived until age 90. I enjoyed reading his life story and learned he had some tough times before, during and after the war. Mr. Iovino and his fellow soldiers were certainly part of America’s greatest generation and we should never forget them. My prayers and thanks go out to the Iovino family and thanks for the articles on Mr. Iovino and his daughter .

Dear Mr. Sutter, Thank you for your kind comments regarding our Dad. He was the only hero in my life. We so appreciate Veterans and all those who serve our country. We were blessed to have our parents as long as we did. Our parents were married 50 years! That alone was an accomplishment since she was 31 years old when she married our Dad. They were childhood sweethearts. I’m sure it was her love that nursed him through his lifetime and the support of his family was a huge factor. As kids, we didn’t know the full background, all I can remember was watching Back To Bataan and waiting for the ending to see our Dad on TV. Years later, we were able to buy the DVD so he had it for his own collection. All his WWII memoribilia is at ADBC Museum in Wellsburg, West Virginia. You can go online and see his artifacts. I also would like to invite you to see a documentary that my nephew, Lee Iovino made for me on my 70th birthday which was in 2022. My nephew went to West Virginia and filmed the museum in this documentary.

Here is the link: https://youtu.be/tEihXzPLolU?si=ZZPHd5AAH4T-uZgv

Thank you again for honoring our Dad.

Sincerely,

Linda Iovino

Linda thanks for your reply. I will check into the information you’ve shared about your Dad. I appreciate you making that available. Hopefully there are some younger family members that will continue to keep his memory alive.

On a side note I have my Dad’s (he passed in 2018) accordion which I guess I need to learn how to play!

So good to hear from you! Take care.