Having participated in the liberation of Dachau during World War II, Joe Sacco inspired his son to write a book that bears witness to the atrocities he encountered.

Having participated in the liberation of Dachau during World War II, Joe Sacco inspired his son to write a book that bears witness to the atrocities he encountered.

When I was a boy, my father often told me stories about World War II. I would listen with wide-eyed fascination as he recounted tales of how he and his buddies fought their way across Europe under the leadership of Gen. George S. Patton. He showed me Nazi swords, daggers and other artifacts he had collected as his battalion stormed through France and Germany en route to the ultimate victory. But there was more to the story than he could share with such a young boy.

One day, shortly after my 12th birthday, he said that he wanted to show me something that had occurred during the war.

“This happened at a concentration camp,” he told me, holding up a small photo album.

“What’s a concentration camp?” I asked, having never heard the term.

“The Nazis were killing people there,” he said, “but we made them stop.”

Inside the album were the original photographs he and his buddies had taken on Sunday, April 29, 1945 — the day they had liberated the notorious Nazi concentration camp at Dachau. The unspeakable horrors caught on film, he assured me, were only a glimpse of what he and his buddies had witnessed the morning they had entered the camp.

“I want to show you these for two reasons,” he explained. “First, at some point in your life, someone will try to tell you that the Holocaust didn’t really happen. But it did happen. I was there, and I saw it. Second, I want you to never let anything like this happen again.”

My father, Joe Sacco, was the only son of Italian immigrants. In 1942, he worked on the family farm in Birmingham, Alabama, and, like many of the young soldiers of World War II, he had never been away from home before being drafted. He had never held a weapon more powerful than a BB gun. He had never encountered violence more intense than a schoolyard fight. And the first beach he ever saw was Omaha Beach.

But it was neither Normandy nor the Battle of the Bulge nor even the months of combat through Germany that would bring tears to his eyes decades later. It was the memory of what he had discovered when he entered the gates of Dachau.

I looked at the pictures in disbelief as he told me the story of that day. I was shocked, confused and horrified. How could this atrocity have happened? What type of people could have done such things to their fellow man?

I looked at the pictures in disbelief as he told me the story of that day. I was shocked, confused and horrified. How could this atrocity have happened? What type of people could have done such things to their fellow man?

Among the scenes he recounted was one of looking down into a railcar in which Jewish prisoners had been locked and starved. There, among the lifeless bodies, he spotted a young lady leaning against a corner nursing her infant son. Both mother and baby were dead — she struggling to give her very last drop of life to her newborn, and he struggling to live, to enter a world that would not have him.

To my father, this was the Madonna and Child, the supreme symbols of life and hope, now lying murdered below him. He told me that he prayed that God would forgive him for not getting there sooner so that he could have saved the lady and her baby.

Innocence was lost as I gazed at the album’s graphic images. They, along with my father’s description of the camp, would haunt me for months on end.

The fact of the Holocaust was undeniable. The pictures proved it. But what was I to make of my father’s mandate to never let this happen again? How could I ever prevent such cruelty, such inhumanity from happening in the future, especially when it had taken the full might of the United States Army to stop the atrocities at Dachau?

Though the years passed, the images of Dachau would not leave me. Through my father’s eyes — and through the lens of his camera — I had witnessed the worst of man, the systematic murder of millions of people for religious and political reasons. These were heinous crimes against humanity, and the cries of the innocents would echo through the ages.

In April of 1981, while traveling through Germany, I visited Dachau. The overcast sky seemed identical to the one in the photos my father had taken some 36 years earlier. The camp was shrouded in stillness and an eerie silence.

I took a pen and notebook from my pocket and wrote the following words:

“They say that the birds never sing at Dachau. Perhaps they cannot produce their wondrous music in a place that has witnessed such tragedy, such cruelty, such horror. Perhaps God forbids it. Or perhaps, on their own, they are muted by the profound sense of sadness that permeates the very air around Dachau — air that once was filled with the cries of innocents and the lingering smoke of their ashes.”

My father and his buddies left Dachau the morning after the liberation, having brought some semblance of humanity back to this place that had endured so much tragedy and sorrow.

“Now, after a year of combat,” he told me, “each of us finally and forever understood why destiny had called us to travel so far from the land of our birth and to fight for people we did not know. And so it was here, in this place abandoned by God and accursed by men, that we came to discover the meaning of our mission.”

He had said that for several years after WWII, he would not speak about it. He didn’t think anyone would be able to fully understand the magnitude and significance of what he and his buddies had experienced. His eventual decision to tell me about the war and to show me the photographs of Dachau, therefore, was not made lightly.

He knew that the stories were heartbreaking and the images were frightening, but he thought it important for his son to understand what he had witnessed firsthand so many years before.

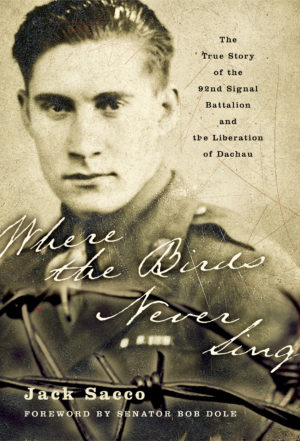

In 2001, I set about the task of interviewing my father and his fellow liberators in preparation for my book, Where the Birds Never Sing.

In 2001, I set about the task of interviewing my father and his fellow liberators in preparation for my book, Where the Birds Never Sing.

Just as my father had done, each told me outstanding stories about the war and each recounted their personal experiences as they entered Dachau. To a man, each welled up with tears as they described the emotions of that day. And each confirmed that it was at Dachau, as they looked into the grateful eyes of those they had saved, that they came to understand the purpose behind their many sacrifices.

Bringing their story to life was not simply a labor of love, but, more importantly, a tribute to what my father and his buddies achieved, for the Holocaust and its carnage ended the minute the Americans entered the camp.

As my father had enjoined me to do so many years before, “Where the Birds Never Sing” bears witness to the truth of the Holocaust. And by bearing witness to that truth, I seek to do my part to ensure that the atrocities of the past are never repeated.

“Where the Birds Never Sing” by Jack Sacco is published by HarperCollins Publishers. (www.JackSacco.com)

The above appears in the May 2019 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian