John F. Misasi passed away on Oct. 13, 2015. The quotes in this article come from an interview conducted and archived by the Melrose Park Library’s Veterans History Project and are used with the library’s permission. (mpplibrary.org/vhp)

As a mechanic and driver during World War II, John Misasi helped keep the American tank assault rolling across Europe toward the Nazi capital.

One of three children, John Misasi was born in Melrose Park to Francesco and Maria Nardi Misasi. Both parents emigrated from Calabria, his father from Paterno and his mother from Dipignano.

Misasi grew up in Melrose Park with his extended family just blocks away. They visited each other regularly and shared Sunday dinners. He especially loved his mother’s homemade pasta, bread and chinulille, a Calabrian cookie specialty. He graduated from Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Grade School and Proviso East High School.

Misasi remembered listening to the radio with his family on Dec. 7, 1941. “That’s where I heard about Pearl Harbor, and I knew there was one fellow on the Arizona from Melrose Park,” he said. The sailor, 17 years old, needed parental permission to join the Navy; his dad refused, but the young man kept pestering him until he finally consented. “His dad never felt right after that because he felt that he was responsible for his son passing away under that condition,” Misasi said. “He did what the son wanted him to do — let him go, so he went.”

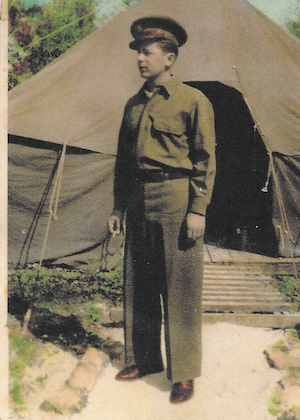

Nineteen-year-old Misasi was working as an apprentice machinist when he was drafted into the U.S. Army in September 1942. Two weeks later, he was sworn in at Camp Grant, Illinois, and boarded a train to Fort Lewis, Washington.

After completing basic training, he was stationed at Camp Laguna, Arizona. “When I got there, they had a sign on the wall: ‘Who wants to go to school?’” Misasi said. “So I signed up, and within two days, I was at Fort Knox, Kentucky.” He learned to be a truck and tractor mechanic, to use a 10-ton wrecker and to drive an M5 Stuart light tank.

After completing basic training, he was stationed at Camp Laguna, Arizona. “When I got there, they had a sign on the wall: ‘Who wants to go to school?’” Misasi said. “So I signed up, and within two days, I was at Fort Knox, Kentucky.” He learned to be a truck and tractor mechanic, to use a 10-ton wrecker and to drive an M5 Stuart light tank.

Misasi graduated as Technician Fifth Grade (T/5) and returned to Camp Laguna, assigned to the 742nd Light Tank Battalion. “Our duty was to protect the coast from the Japanese at that time, and we also trained to go to Africa in the desert,” he said.

As the African campaign ended, Misasi went to Camp Polk, Louisiana, for what he called “swamp training” in an environment similar to what would be faced in the South Pacific. He was then transferred to the 771st Field Artillery Battalion because they needed mechanics. Misasi completed training maneuvers and was stationed at Camp Hood, Texas, and then Camp Shanks, New York.

He boarded a troop ship on July 1, 1944, and headed for England. “There was such an armada of ships that you couldn’t see the end,” Misasi said. As they approached Liverpool, a German submarine chased them “way up north.” Anti-sub units came to their rescue, and the ship returned to Liverpool. “We didn’t know what was going on. All we knew was that we had to cross the channel, and we were field artillery so it wasn’t hand-to-hand combat,” Misasi said. “We were lucky in that part.”

After landing on Utah Beach on Aug. 20, 1944, Misasi and his unit headed to Brest, a German submarine base. “It took us a good month with airpower dropping bombs and artillery dropping bombs,” said Misasi. Underground fortifications were made of steel and concrete six feet thick, and the Germans had enough food to last for years. “But the tremors (from the bombs) were so great that they couldn’t stand it anymore,” Misasi said. “So they gave up, and our battle was over with that area.”

They then pushed toward Paris, engaging in “small skirmishes” in Nancy and other towns along the way. By the time they arrived, Paris had already been liberated. “We marched down the Champs-Élysées under the Arc De Triomphe, and we felt like we had accomplished something,” Misasi said.

His unit advanced to St. Vith and fought in the Battle of the Bulge. “The German soldiers were dressed in white to match the snow,” he said. The weather was bitter cold, snowy and too foggy for airpower, and the Germans, knowing the landscape, brutally attacked. “Our infantry was annihilated,” Misasi said. He crouched with his bazooka, ready to fire and disable a tank. “However, when it did come toward me, I couldn’t see who it was, whether it was American or German, so I had to let it go by,” Misasi said. “I didn’t even see it. I just heard it.”

After artillery fire knocked out the German guns, Misasi’s unit was ordered to “take off” to the France border, where Misasi was assigned to drive his captain to the front lines. He remembered entering a room. “There were generals and captains, all kinds of brass with maps on the wall, and they’re figuring out what their next move was going to be.” For 13 days, Misasi drove the captain back and forth between headquarters and the front lines in an open jeep.

After the Battle of the Bulge, Misasi and his unit went to Luxembourg to halt the SS troops. “The young ladies would come and put homemade medals on us to thank us for saving them from the SS troops.”

At night, the soldiers dug slit trenches for protection. “When they dropped bombs, shrapnel would fly through the entire area, and you’d find shrapnel on the side of your slit trench. The dirt that you would put on top would catch the steel fragments,” Misasi said. As they were building their shelters near the Rhine River, the sandy soil kept caving in, so Misasi and his buddy built a fort-like room from sod in the forest. “During a barrage, other soldiers ran for cover and jumped into our shelter. There were about 20 of us in there,” Misasi said. “Luckily, they didn’t shoot a bomb in there.”

Occasionally, they sheltered overnight in a house with civilians. “We’d often give them some of our food, some flour, some sugar, and they might make some cookies or something like that,” Misasi said.

The “Red Ball Express” delivered supplies to the front lines, and the vehicles frequently broke down. “Every once in a while, they’d bring 10 or 15 back to us,” Misasi said, “so we were always working, putting things together.”

From July 1944 to May 1945, Misasi set foot in seven European countries, advancing through villages and countryside, fighting in four major battles and traveling more than 2,400 miles, from England to Czechoslovakia, with the 771st Field Artillery as a mechanic and tank driver. His unit was assigned to POW camps in Germany when the war ended.

T/5 Misasi was discharged in December 1945 and returned to Melrose Park. Among his many medals were four battle stars. He and his wife, Josephine Dodaro Misasi, had three children, three grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. He retired as a tool gauge inspector.

“I was always in favor of being in the Army. I did the best I could, and I was proud,” Misasi said in the library interview. He told his daughter, “There is NO COUNTRY like the United States of America.”

The above appears in the May 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian