I grew up in an era when our parents had their friends and we would refer to them as “Aunt” or “Uncle.” Later in life, we discovered they were not related to us. It was a little like when we discovered Santa Claus was just Dad in a red coat and a beard. I never asked my folks why they insisted I call them Auntie Virg and Uncle Bill. I was also surprised how many of my Dad’s colleagues at his job were Aunties and Uncles.

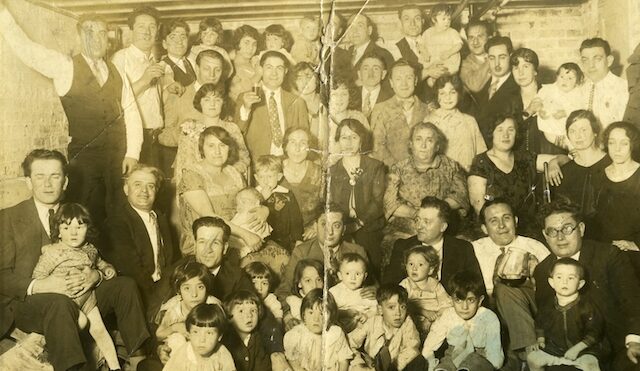

When it came to family, nobody was my Aunt or Uncle unless they were my Dad’s brother and sister-in-law, or my Mom’s brothers and sisters and their spouses. However, everyone was my cousin. We have all been to a wedding when we were kids, and we were picked up and hugged and kissed by about a thousand cousins!

So when the Auntie and Uncle thing turned out to be a hoax, I thought the “everyone’s my cousin” thing was a hoax, too. But, no, it wasn’t. Yes many of these people were cousins in one way or another and sometimes nobody could figure out how Carlo was related to my mom but they knew her other cousin Carl was her uncle’s Joe’s son.

Keep in mind that I’m talking about Chicagoland. This is a huge metropolitan area with millions of people who are totally unrelated to each other. But if we are talking about the small town in Italia where our families come from, we have a very different picture.

My mother’s father came with his mother and siblings from Triggiano, a small town near the city of Bari. His father came over in 1906, and died on the day he arrived at Ellis Island, and it took a few years for great-grandma to remarry and her new husband to emigrate to Chicago for better work and better pay, and then the rest of the family came over in 1914. Triggiano had a population of about 5000 in the early 1800s and about 25,000 today, so it’s the size of a small Chicago suburb.

Today everyone can get from town to town via cars or scooters, and can fly around Italy, Europe and to America on jet planes. Back in the 1800s and early 1900s, they had no motorized transportation. Everything was horse and buggy. So it was slow and difficult to travel even between towns. Due to local dialects, it was difficult to communicate with people from a different province. It was more comfortable to talk to people who spoke your town’s language, who you knew all of your life.

So let’s compare Chicagoland to Triggiano. In the 2000s, how many of your Chicago relatives meet and marry people who are only from the same little town in Italy? On the first date, who asks the other person “So what little European town is your family from” and then abruptly asks for the check when they aren’t from the right place? On the other hand, our relatives in Triggiano (and your small town too) had to mostly be content with meeting and marrying someone from that same small town.

Since I have studied all marriages in Triggiano from the 1700s to the mid 1900s, I have the following data that might be similar to your town in Italy. (Maybe more so if your town is in the mountains or even harder to get in or out of than Triggiano is.)

The marriages in Triggiano from 1750 to 1900 show that both bride and groom were born in Triggiano in over 5000 instances. Either the groom or bride came from another town 1500 times.

So around 75% of marriages happened between couples from the same town, prior to the use of better modes of transportation. From 1901-1945 (those are the latest marriages I can access) this number changes quite a bit. About 2600 marriages in Triggiano between couples both from there, and 1700 marriages from “mixed” towns. But that’s still over 60% of the marriages within that town are from amongst its own residents. I wish I had data from the past 50-75 years. I’m sure it is much less insular.

How often did the people from Triggiano marry from outside their province? Out of 6700 marriages from 1745-1900, a miniscule 54 took place between a person from Triggiano and someone from another province, less than 1 percent. From 1901-1945, with more modern transportation, it’s still around 5%, and that includes a lot of wartime marriages when soldiers were in completely different provinces and regions than they were born in.

I do not have the statistics but I have noticed a pattern from among widows and widowers that they frequently remarried people from a nearby different town. This is especially true if they are both middle-aged and their children have married and moved. If my observation of this trend is accurate, it actually might skew the results toward more “mixed town” marriages.

Obviously it isn’t just the inability to go from place to place that made it more unlikely that someone from a small Italian town would marry someone from another town. Everyone has heard of the “arranged” marriage. The father of the future bride would try to match her up with someone who would be able to be a good husband, father and provider. Sometimes the mothers were involved too! So it would be more likely to match up your daughter with someone from the town from among the people you already know. Why try to give your daughter for life to some man you never heard of?

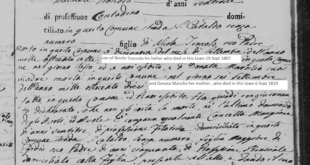

So if huge percentages of people chose their local kinfolk to marry, or had those kinfolk chosen for them, did people marry their close cousins? The answer: rarely. Neither the Church nor the State wanted people to marry close kin, and most people didn’t want to marry their close cousins either. When a couple wanted to marry (or their parents wanted them to marry) there would be the marriage banns, known as Pubblicazioni. This gave the townsfolk a chance to object to the marriage. More often than not, the father of the bride would be the one who would object to the man she wanted to marry. There is no record of what was said when such things occurred, but when you find a couple in the banns but not in the marriage records, that’s a good clue. During the process of determining whether the marriage can take place, a number of documents were drawn up. They would find the birth certificates of the bride and the groom and copy them. They would search the town marriages to make sure neither was married. (What if either one married somewhere else?) If either the groom or bride were previously married and had been widowed, a copy of the death record of the prior spouse(s) was made. If it was determined that the bride and groom were 2nd cousin or closer, they needed dispensation from their fathers and the Church to marry. If the father of the bride was living and working in the United States or elsewhere, a document of his permission would be sent from a notary where the father lived, to the city where the marriage was to take place. If the father of either the groom or the bride had died and could not grant permission for the wedding, a copy of his death certificate would be filed. If there was no dowry, a “certifcato di povera” was filed.

All of these papers for each wedding ended up in a separate record type called the “Allegati”. We will talk about how great these are next month!

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian