by Rosa Morici Rappa as told to Linda Grisolia

An American citizen who died in a Soviet prison camp as a member of the Italian army during World War II, Vincenzo wrote a letter to his family that finally arrived more than 60 years later.

My father, Vincenzo Morici, was the youngest of six children. He was born in New York City on March 14, 1918, to Diego and Rosa Lo Baido Morici. His father had emigrated to Chicago from Borgetto, a small town near Palermo, got settled, and then sent for his wife and five children.

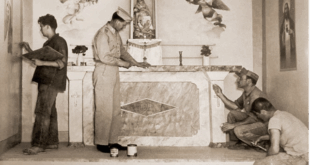

My father attended grade school in New York City and grew up in a close-knit family. As his father grew older and became sick, he wanted to return home to Italy. My father was 12 years old when he moved to Borgetto with his parents. Some of his brothers and sisters came with him, and some stayed in New York. My father took care of his parents, worked the land and maintained the household as he grew into a young man. He married my mother, Maria Rizzone, and they lived in a house next to my grandparents. In mid-1938, he was called to be in the Italian army. My grandfather was so sick at the time that he was confined to a wheelchair.

My father did not want to go into the army. Who would take care of his family? Who would take care of the two houses and land? Born in New York, he was an American citizen. He tried and tried to get out of it, talking to the officials, but they told him, “No, no, you got to go in the army. You got to go.” He left for the army in March 1939. My brother Philip was born in October 1939.

My father did not want to go into the army. Who would take care of his family? Who would take care of the two houses and land? Born in New York, he was an American citizen. He tried and tried to get out of it, talking to the officials, but they told him, “No, no, you got to go in the army. You got to go.” He left for the army in March 1939. My brother Philip was born in October 1939.

From time to time, he was given a few days off to be with his family, and I was born in September 1940. My father continued to visit periodically and write to my mother until Mussolini ordered his regiment to advance into Russia in September 1942.

We did not see or hear from him after that. Frantic and wondering where my father was, my mother and grandmother continuously wrote to the Italian government asking for help. The answer was always the same: He is lost. Everybody — relatives, cousins, people in our small town — waited for his return. Soldiers who had known my father and returned from the war looked in on us with sadness in their eyes. My grandmother gave strength to my mother, who wept by herself when nobody else was looking. Out in the field, she cried, “Where are you? Where are you?”

Years passed, and my brother and I grew up without our father, always hoping and praying he would come back. At the age of 12, Philip moved to New York to be with our aunts and uncles, who had all returned there after the war. He attended school, married and had a successful career. I married, moved to the United States with my husband and had two daughters. My mother lived with us, and we never stopped wondering what happened to my dad.

In 1991, Russia released World War II military documents that had been held in a secret archive in Moscow. Finally, after 52 years of waiting, we received a letter from the Italian government explaining what had happened to my father. His regiment entered Russia in September 1942. My father was captured at Bocuciar on Jan. 17, 1943, and taken to Camp #72 Varnavino, where he died as a prisoner of war in May 1943. He was buried in a mass burial plot with soldiers from other countries. A map showing prison camps and the approximate burial location was sent along with the letter. Until we received these documents, my father had been considered “lost.” You can just imagine how we felt to receive those papers. Sad as we were, at least now we knew what had happened.

In 2009, my grandson Pierfranco, then a lieutenant in the Italian army, was stationed in Palermo. He learned that documents from World War I and World War II were stored in the building where he worked and was curious if he might find out something about his great-grandfather Vincenzo. He was surprised when his inquiry led to a faded blue folder with MORICI VINCENZO scribbled across it.

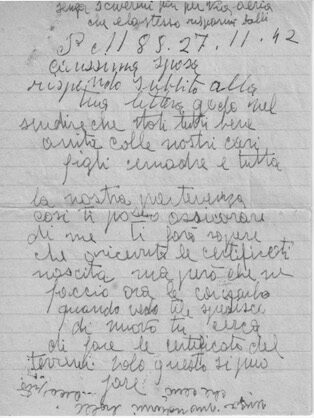

A letter Pierfranco wrote in Italian for the 2017 Festa Della Republica program describes what followed. He leafed through the documents slowly, reading every detail in order to feel close to his great-grandfather and that terrible time long ago. Suddenly, he was holding a folded sheet of notebook paper, yellowed with age, written in old calligraphy. As he began reading, he understood it was written by his great-grandfather on Nov. 27, 1942. “I started reading the letter and I felt tears coming down. The more I read, the more I cry. Più leggo, Più piango. I am proud to hold in my hands something my great-grandfather wrote 66 years ago.”

Pierfranco took the folder to his mother, and together they called my mother and me. My daughter said, “Mom, I got something to tell you!” Then, she couldn’t talk. Pierfranco picked up the phone, and together, their voices choked with emotion, little by little they explained the blue folder and the letter. I was so emotional that I couldn’t talk. My mother kept asking, “What’s the matter? What’s happening?” and she got on the phone. We were shaking for days after that, as we realized what Pierfranco had discovered and its importance. At last, we had something from my father after all these years.

Pierfranco took the folder to his mother, and together they called my mother and me. My daughter said, “Mom, I got something to tell you!” Then, she couldn’t talk. Pierfranco picked up the phone, and together, their voices choked with emotion, little by little they explained the blue folder and the letter. I was so emotional that I couldn’t talk. My mother kept asking, “What’s the matter? What’s happening?” and she got on the phone. We were shaking for days after that, as we realized what Pierfranco had discovered and its importance. At last, we had something from my father after all these years.

The blue folder was given to us, and my mother was finally able to hold the letter in her hands and read the words my father had written to her 66 years ago. In the letter, addressed in Italian to “My Dear Wife,” he responds to her last letter and is happy to hear that she, their children, mother and all their relatives are well. He is well, too. “I write in the dark, that one cannot see anything, my hands are shaking and cramped with the cold. Have courage, there is nothing we can do.”

He sends greetings to all his relatives and friends in town. He is sorry he is away and worried about the land and his horse. He asks about his children. “Let me know if Rosa walks and if the fields are seeded.” He sends hugs and kisses to his wife and children, and kisses the right hand of his mother and asks for her blessing. He ends with “Buon Natale!”

In 2009, my father was awarded the Diploma Di Onore (Diploma of Honor) and La Croce al Merito di Guerra (War Cross of Merit) by the Italian government. The recognition and honor were long overdue.

I was a baby when my father left for the war and have no memory of him, but after 66 years, I have his letter. Holding it in my hands, reading his words, I finally got to know a little bit about my father.

The above appears in the August 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian