In his tireless dedication to the downtrodden, Anthony D’Urso follows in the footsteps of his heroic parents.

New York City was no place to land alone in 1960 without a job, high school education or social safety net. Now imagine not speaking a lick of English when you stepped off the plane from Italy at the age of 21. What was a young man to do?

For Antonio D’Urso, answers came, one after another, in terms any immigrant would understand. Work hard. Learn the language. Get an education. And not just any education in D’Urso’s case, but a 16-year academic odyssey that took him all the way to a master’s degree. Then again, how could he not be so determined and brave? As a child, he took part as his father hid their Jewish neighbors from the Nazis during World War II.

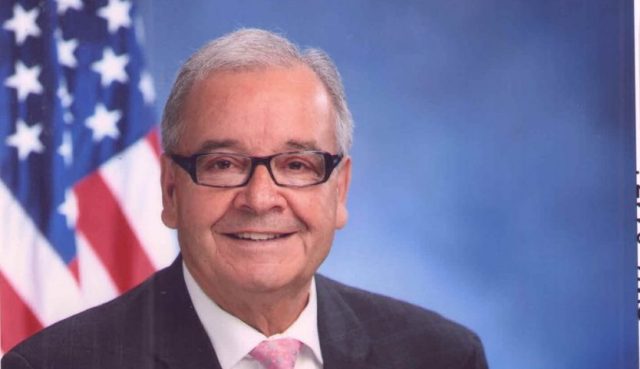

A longtime public servant in New York City’s public housing system, an elected official on local and state levels, and a volunteer in some of the world’s most destitute and dangerous places, New York Assemblyman Anthony “Tony” D’Urso embodies all a great and generous man should be. He shared stories with Lou&A about his Italian upbringing and a lifetime of variations on the theme of service.

Lou&A: Tell us about your roots in Italy.

Anthony D’Urso: I was born and raised in Formia, a town of about 36,000 halfway between Rome and Naples. It’s right on the Mediterranean Sea. The ancient Roman road, the Appian Way, goes through the town.

Lou&A: From the start of your life, you saw your parents model generosity and bravery in a historic way. Could you share that story with us?

D’Urso: It was World War II, and the Jews had to find refuge somewhere from the German soldiers. I’m very proud that my father decided to take two families — the only Jews in that area — and hide them. We shared what little food we had with 12 additional people, and we moved them at night when the Nazis were getting too close. It was a difficult, dangerous time, but we got it done.

Lou&A: Then came the recent discovery of diaries written by two of the family members. How did that happen?

D’Urso: In the summer of 2017, a friend of mine found out that there was a synagogue in Naples and coordinated an encounter with them. After 74 years, I went to Naples with my wife, and we reunited with the descendants. We were given diaries written by two survivors. It was very emotional.

Lou&A: You’ve sought recognition from Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, for your father’s role. Where does that stand now?

D’Urso: We’re getting close to it. We’d like to see him added to the list of the Righteous Among the Nations for his role in protecting Jews. But if not, we know it and our families know it, and that’s good enough for us.

Lou&A: What made you want to come to the United States at age 21, especially since you couldn’t speak English? You had just eight years of formal education to boot.

D’Urso: I was the only one in my family of six who had more than five years of schooling in Italy. I had a thirst for knowledge, and I told my father I wanted to go to even more school in Italy. He said no, so I came here because I wanted to learn more.

Lou&A: And from what I understand, you wanted that education pretty badly.

D’Urso: I came here alone. My parents didn’t want me to come to America. And yet, my father found a way to make me eligible to emigrate through a French quota. There were 400,000 Italians in line for 4,900 U.S. visas, but because the French had 49,000 visas and my father had French citizenship, that’s how I got in.

I washed dishes in the catering halls. I cleaned cesspools. I loaded trucks in a furniture factory. I worked as a carpenter and bricklayer. For 16 years, I went to school after work. I had to learn English, and I got a high school diploma, then an associate’s degree and finally my bachelor’s degree at the Pratt Institute School of Architecture. I did all that while my wife and I raised four kids.

Lou&A: But you didn’t stop there.

D’Urso: I was working for the New York City Department of Housing before I graduated. Once I got my master’s degree from Pratt, I rose through the ranks to become assistant commissioner of the Division of Architecture Engineering and Construction. I worked for the city for more than 30 years. Many parts of the city burned down during the civil rights riots, and I was in charge of designing new apartments as part of a slum clearance. We built for the homeless and low-income people: 2,000 apartments a year without any extra taxpayer money. Imagine that!

Lou&A: Before you became a state assemblyman, you also served as a councilman in North Hempstead, New York, for 14 years. Along the way, you’ve done some extraordinary charitable work. Those stories alone could fill many pages. I’d love to hear some highlights.

D’Urso: I’ve spent a lot of money from my pension — and my wife from hers — to save as many children from starvation as possible. I’ve made 10 trips to Africa, including to the biggest slum on the continent: Kibera, outside Nairobi. They have no water, no sewers, no electricity. Nothing. But we’ve provided food, clothing, shelter and a modicum of health care. It gives me great, great pleasure. The children with the swollen bellies are getting fed, and when I’m there, the children surround me with so much affection. You feel so tall and so proud.

I’ve made 17 trips to Nicaragua, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere after Haiti. I raised money to build maybe two dozen small houses there. We’ve built water projects, schools, a community center and even a little bridge. There was a small town where a river splits it, and when the heavy rains came, people couldn’t get from one side to the other.

Lou&A: Speaking of Haiti, you put yourself at risk there much like your father did.

D’Urso: I’ve made eight trips to Haiti after the earthquake in 2010 that killed 316,000 people. There was an image I could never get out of my mind — a bulldozer scooping up dead bodies and putting them in a truck. There was no reliable electricity, so we installed solar panels at an orphanage and fed and clothed them.

Lou&A: How do you connect your generosity to your upbringing?

D’Urso: My parents always preached that no matter how little you have, you share it with people who have less. Back in Italy, we used to boil beans and drink the water from the beans. There was a family in a hut that had even less than us. My mother would always share something with them. Always. How could you grow up and not be affected by that? It’s what you have to do. You just have to.

The above appears in the July 2020 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian