After guarding the Korean DMZ for most of his tour of duty in the Army during the Vietnam War, Luco Clarizio watched over fallen soldiers returning to the States, escorting their caskets from the airport to the cemetery.

The oldest of two sons born to Dominick and Mary (Viola) Clarizio, Luco was brought into this world by his maternal grandmother in a fourth-floor walk-up on Loomis Street in Little Italy. “I was born blue, and my grandma put me in the oven,” he says. His parents were born in Chicago, and his grandparents emigrated from Calabria and Bari.

The family lived on Loomis Street for four years until his parents divorced. Clarizio and his younger brother lived briefly with the Viola family before moving in with his father, grandfather, aunt and uncle. Eventually, they bought a two-flat on the South Side of Chicago. Clarizio grew up surrounded by aunts, uncles and cousins on both sides of the family. “I had two places to go and two places to eat,” he says. “It was really nice. You didn’t go a week without seeing them. Everything was family oriented then.”

He graduated from Luke O’Toole Grade School and attended Harper High School, playing many sports. “My biggest fan, Uncle Botty, was at every game,” Clarizio says. “He was like a father to me because we all lived together.” His Aunt Antoinette also lived with them. “She made the homemade raviolis, and I used to help her,” Clarizio remembers. “She gave up a lot of her life to take care of us.”

Graduating high school in January 1966, Clarizio was offered baseball and football scholarships to several Big Ten universities. He was in the middle of college visits when he was drafted in July 1966. “Uncle Sam gave me a nice diploma,” Clarizio chuckles. “I was shocked. I expected to go to school, to tell you the truth.”

He reported for his physical downtown, where they were drafting for the Army and Marines. The men stood in line in their skivvies as they were counted off: Army, Marine, Army, Marine, etc. Clarizio was selected for the Army. “I went downtown, and I stayed downtown,” he says. “My dad had to come and get my car. I didn’t get to say goodbye to nobody.”

He reported for his physical downtown, where they were drafting for the Army and Marines. The men stood in line in their skivvies as they were counted off: Army, Marine, Army, Marine, etc. Clarizio was selected for the Army. “I went downtown, and I stayed downtown,” he says. “My dad had to come and get my car. I didn’t get to say goodbye to nobody.”

Clarizio boarded a train to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, where he completed Basic and Advanced Infantry Training. He was assigned to the Seventh Infantry Division, 13th Engineer Battalion. “We were being trained for Vietnam. Then our whole company caught spinal meningitis, and we were all hospitalized for about two weeks,” Clarizio says. By the time they recuperated, the troops had already deployed. “Everything was messed up,” he says. Clarizio’s company was reassigned to Korea. “Everybody [in the family] was happy I went to Korea,” he says, especially because his father and three uncles served during World War II, with one fighting in the Battle of the Bulge.

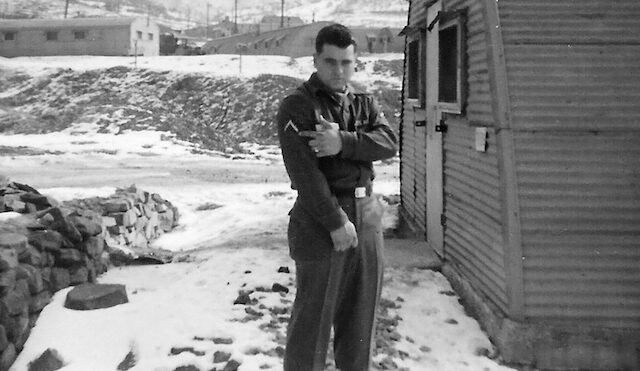

Clarizio arrived in Korea in January 1967 and was stationed at Camp Casey, near the Demilitarized Zone. In camp, he lived in barracks, but as a member of the Combat Engineers, he spent most of his time in the field. The first night, fully clothed in his sleeping bag in below-zero temperatures, he could not get warm. “I never was so cold in my life,” says Clarizio. His sergeant yelled, “Take your clothes off, dummy!” Clarizio undressed, warmed up in his sleeping bag and fell asleep. He woke up for guard duty and grabbed his clothes, which he had flung outside the sleeping bag. “Everything was frozen, and I had to put all that stuff on and get up the hill and walk the guard duty,” Clarizio says.

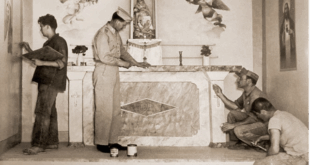

His job was building and maintaining roads, Bailey bridges and floating bridges; demolishing any obstacles that stood in the way; and keeping the trucks in tip-top shape. He also rotated on guard duty. “We had to protect our bridges, and we had to worry about infiltrators that would come across [the DMZ]. We were busy all the time,” Clarizio says. “Whatever they wanted, you did.”

The soldiers rode in the back of dump trucks with their duffel bags as they traveled from one workplace to another. Upon arrival at Camp Casey, the sergeant asked who was Italian and who was from Chicago. “There were six of us, and I didn’t know what they wanted,” he says.

They were chosen to guard the duffel bags. The South Korean people were very poor, and as the soldiers jumped on and off to shovel sand onto the roads or perform other duties, “slicky boys” jumped onto the trucks, threw the gear down and ran off with it. “They would steal anything, so you had to watch them,” Clarizio says. “We were told, ‘Anybody who comes on the truck, you throw them off.’”

Bridges were especially vulnerable, as the South Koreans would pillage them for steel parts. “They knew exactly what to take off,” says Clarizio. “If you tried to go across, it would collapse.”

Children, some carrying younger ones, watched the soldiers as they ate. “I’d say, ‘Here, take this,’ and gave them food,” he recalls. “You feel guilty even though it’s your food … little kids begging for your food,” Clarizio says. “It was a rough time for me because I wasn’t used to it at all, and to see all the [poor] people … it was a sad state.”

Clarizio became acting sergeant and was promoted during his 13 months in Korea. He returned to the States in 1968, was once again stationed at Ft. Leonard Wood and lived in the barracks with the trainees. “Everywhere they went, I went,” he says.

Clarizio volunteered to escort bodies returning from Vietnam. “I didn’t know what it would entail,” he says. Clarizio represented the Army as he met the casket at the airport and stayed with it until burial. He met with the soldiers’ families and stood at attention at the funeral home. “Whatever [the family] wanted us to do, we had to do,” Clarizio says. “If they wanted us to open it, we had to open the casket, but you’d try to talk them out of it.”

Clarizio was discharged in July 1968 and returned to Chicago. He married Mary Lou Ingram in 1969, and they have five children and seven grandchildren. Clarizio drove a truck for 30 years and was a fireman/paramedic in his community for 17 years. He also managed the ground unit for the Air Angels, a company that provides emergency air transport.

Had it not been for spinal meningitis, Clarizio would have deployed to Vietnam. Reflecting upon that, he says, “I went wherever they sent me, did the orders they gave me and tried to make the best of it that I could.” Remembering the escort duty, Clarizio says, “There were so many bodies coming home. It really upset me because I figured I should have been in Vietnam, but I don’t know. I might have been dead, too … you don’t know.”

The above appears in the July 2021 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian