Trained to fight in the deserts of North Africa during World War II, he earned the coveted Air Medal while organizing and overseeing a mission to bring desperately needed supplies to embattled troops in the jungles of the South Pacific.

Trained to fight in the deserts of North Africa during World War II, he earned the coveted Air Medal while organizing and overseeing a mission to bring desperately needed supplies to embattled troops in the jungles of the South Pacific.

Editor’s Note: The following profile was assembled from the diaries of Vincent Allegrini, interviews with his son Robert, and the official history of the 33rd Infantry Division. Allegrini’s uniform and decorations can be found at the Italian American War Veterans Museum at Casa Italia.

In late December of 1944, units of the Army’s fabled 33rd Golden Cross Division, comprised primarily of soldiers from Illinois, were engaged in a ferocious firefight with the Japanese in a dense jungle on the island of Morotai in the Netherlands East Indies. For the Americans the situation appeared desperate as an entire regiment had expended most of its ammunition in battle. Rations and medical supplies were also running low.

That’s when the 33rd Division turned to 1st Lieutenant Vincent Allegrini, a quartermaster officer from the Austin neighborhood of Chicago, to organize a mission to resupply the endangered elements of the division by air beginning on Dec. 23 and lasting into January. As the first parcels of food and ammunition began falling from the sky on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, the American troops gave thanks for a Santa Claus of a different sort. But for Allegrini, it was no sleigh ride. Determined to personally oversee the resupply effort, Allegrini’s C 47 cargo plane was flown at an altitude of only 200 feet as enemy fire exploded all around him.

The mission was a great success, with 95 percent of the supplies reaching the American troops. Soon the troubled regiment was on the move again, and by the Feast of the Epiphany on Jan. 6 the battle was over, with 870 enemy losses to only 46 of their own.

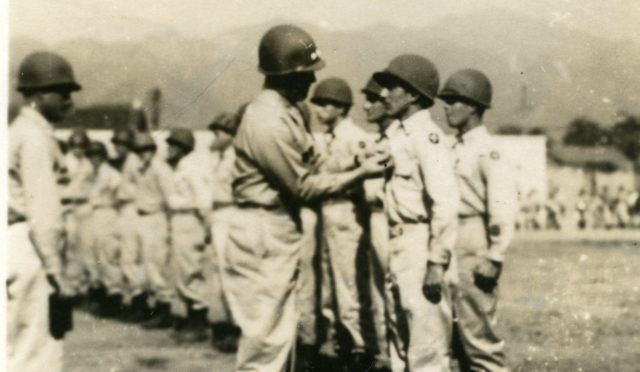

For his role in organizing the resupply mission, Allegrini was awarded the coveted Air Medal — one of only 40 conferred on the division of more than 13,000 men during the entire Second World War. His official citation from General P.W. Clarkson reads, “With disregard for his safety Lt. Allegrini ignored the hazards of low altitude flights over mountain terrain and hostile fire, performing his duty in a manner which contributed materially to the success of the campaign and reflected the highest degree of credit to himself and the military service”

As Allegrini proudly wore his medal, he contemplated the surreptitious route that took him from the comforts of Chicago to the privations of South Pacific jungles.

Just three years earlier, on the afternoon of Dec. 7, 1941, the 23-year-old Allegrini was sprawled on the floor of his living room listening to the radio and reading the Sunday newspaper when an announcer broke into the broadcast to give the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. He realized at that moment that his life would be forever changed. He had been studying finance at Northwestern University and was working as a junior accountant for the Commercial Investment Trust Corporation. But like thousands of other young Americans he knew he had to answer his country’s call to duty. As an only child, his sole concern was leaving his widowed, Italian-born mother alone. With her grudging support, he volunteered for service and reported to Camp Grant in Rockford, Ill.

From Camp Grant, he was sent to Fort Warren in Wyoming where he was accepted into Officers Candidate School. As he took up his diary again after successfully completing the schooling, he noted, “Today, I write not as an enlisted man but as an officer. Yes, on the 23rd day of December 1942 I realized my ambition … that of being an officer.”

Upon accepting his commission, Allegrini moved to join the 33rd Division at Fort Lewis near Tacoma, Wash. After several months of extensive training in the Pacific Northwest, the division was transferred to the Mojave Desert where it was trained for desert warfare. It looked like the division was destined to do battle in the North African Theater. That was just fine with Allegrini, who felt his fluency in both Italian and French — acquired from his mother who hailed from the bilingual Italian/French border region of Val D’Aosta — would be of considerable use there. But the fighting in North Africa ended before the division could make a contribution and as fate had it, the division was sent west to Hawaii to prepare to do battle against the Japanese.

For the next 10 months, the division was stationed on the Hawaiian “garden island” of Kauai. According to Allegrini’s son, Robert, his father’s time in Hawaii was the golden period of his military service. “My father loved everything about Hawaii from the climate to the culture,” said the son, who returned to Kauai with his father in 1978 to visit his old island haunts, many of which had not changed in the intervening 35 years. “I’m convinced my father would have moved to Hawaii after the war had my mother not been attached to her family in Chicago.”

But the 33rd Division soon paid for its lengthy stay in paradise when it was hurled into its first battles in the snake-filled, disease-ridden jungles of New Guinea. The division spent six months there slogging it out with the Japanese before moving on to the battles on Morotai.

During that period, Allegrini repeatedly attempted to transfer to the European theater but the Army had other plans for his linguistic skills. He was ordered to remain with his division in the Pacific and to await taking command of a contingent of Italian prisoners of war. The POWs had volunteered to serve the Allied cause after Italy’s surrender under a very successful program called “Italian Service Units.”

In the end, however, the expected Italian prisoners never materialized and for the 33rd Division, it was on to the pivotal battle to liberate the Philippines. Shortly after arriving on the island of Luzon, Allegrini’ s logistical skills again helped ensure an American victory as he established procedures that allowed his division to receive vital supplies in a minimum of time. For these efforts, Allegrini received a Bronze Star from General Clarkson, who wrote, “Lieutenant Allegrini by his untiring efforts and devotion to duty rendered outstanding service in providing a variety of subsistence items to combat and service troops.”

Allegrini completed his overseas military service as part of the occupying army in Japan, arriving there only two weeks after the Japanese surrender in September 1945 and remaining until December 1945. Ten days after his departure from Japan, his wartime exploits were recognized with a Presidential appointment to the rank of Captain in the United States Army Air Corp.

In the final entry of his diary before shipping out to the front lines in New Guinea, Allegrini wrote, “I pray that someday in the future I may read these words I have written in the peace and comfort of home all safe and sound.” Thankfully, his prayer was answered. Allegrini was discharged from active military service in March of 1946. He married in 1948 and graduated from the University of Wisconsin School of Banking in 1952. A long and successful career in banking followed. Vincent Allegrini passed away on Oct. 26, 2004, at the age of 85.

The above appeared in the March issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian