Dating back some 4,000 years, the sport of falconry is still widely practiced today. With origins in the Middle East, falconry is a highly-regarded pastime, which, in some cultures, also serves as a male rite of passage.

Italian filmmaker Yuri Ancarini explores an annual falconry competition that takes place in the vast desert of Qatar in his visual masterpiece, The Challenge. Ancarini combines the spectacular desert landscape of the Arabian Peninsula with a dramatic soundtrack and candid moments to give an intimate look into the world of the falconers. Several types of predators from the raptor species of birds are used in falconry. Ancarini focuses on hunters with majestic hawks and falcons as they embark on a testosterone-filled weekend of fast cars, motorcycles, meat-feasting, big spending and competition.

The three and a half-minute static shot in the opening scene is a precursor to the patient cinematography and infinite landscapes that are to come. Shortly thereafter, a Qatari sheikh and his pet cheetah set out for the desert roads in a black Lamborghini. Another sheikh travels by plane with his birds. At first, I wasn’t sure what to think because the birds’ eyes were covered and they seemed agitated, constantly turning their heads back and forth while in flight. However, there is a decadence to the scene and thus the consolation that the birds are well-cared for. Anticipation builds as a group of motorcyclists converge on the highway with their extravagant gold-plated bikes. A scene in the desert where boys will be boys revving their engines and racing around the sand followed by a group of men feasting on a huge carcass of meat with their bare hands to one of the final scenes when the sheikhs are engaged in a bidding war for a prized falcon to the closing scene when we finally see what all the fuss is about, makes it clear that Ancarini’s protagonist of The Challenge is none other than this annual event, which celebrates the sport of falconry. The sportsmen themselves are the supporting characters.

My basic requirement of a good film is that it transport you to another world and The Challenge exceeds this requirement. Ancarini presents a compelling portrait of what one culture considers “man’s best friend.”

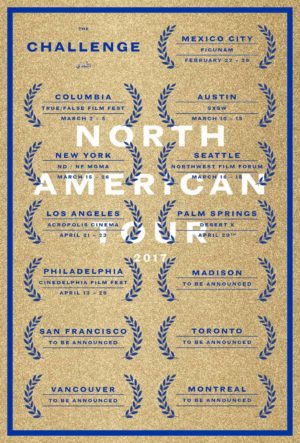

The director is in the middle of a North American tour with the film, which included a screening by the Museum of Modern Art in its annual series, New Directors/New Films. I saw the fascinating film and asked Ancarini about the ancient sport, the importance of the birds to this culture and his unique style of storytelling.

How did this annual event of Falconry come to your attention?

I discovered it out of curiosity. Qatar is a country that until five years ago was unknown to everybody, with a very poor desert, until they found gas fields. Then it became an important place for the world economy. They began to build, they invited artists and the greatest architects of the world. It was a country that I did not know and I was intrigued, since it was a protected country for a long time, and it was closed to us. As it often happens, I went there with some ideas but they didn’t work. I went back several times, and I started to better understand their habits and traditions, then I came up with the idea of The Challenge.

I have some questions about the animal aspect of this film…Could you explain to me why the falcons were turning their heads back and forth on the plane? Were they feeling anxiety from their eyes being covered? And why are they covered so much through the film… during the auction, for example?

All the animals you see are pets. There is a special love towards their animals and the falcon is a venerated creature, almost idolized. There is a very ancient manuscript, dated back to Middle Ages, that tells a story about the fact that the hawk is one of the most violent predators in the ecosystem. If you are pointed out by a Falcon, there is no hope to survive. The same story states that the hawk feels guilty because of his violent attitude and to satisfy this sense guilt, decides to be tamed and to become a companion of humans. The hawk, when he looks, attacks! With the cap, he is calm. So, in the house or in a sheltered environment or when hunting, the head is not covered. Otherwise, he wears a cap. The head movement was an unexpected surprise and it was probably due to the fact that the falcon has a kind of internal GPS in his head. So, being on a plane, he perceives the change of heights and shift. This is an important moment of the film.

How do the falconers and these people in general view the animals? On one hand, they adore them… but on the other hand, the animals seem to experience a lot of stress. I felt this during the opening scene as well as during the flight and towards the end when the falcon was being prepped to show.

The relationship they have with the hawks is almost maniacal to the point that some sheiks do not want their own hawk being watched by strangers. Falconry is an ancient practice of hunting. I tried to represent the reality, so criticizing hunting is up to the viewer. The movie wants to represent a reality and there are more interpretations that the viewer can think about.

Regarding the pigeon bating, do the sportsmen have any remorse for the pigeons? The reason why I ask is because they showed an extraordinary affection for the falcons beyond just seeing them as an object for hunting. I also noticed the gentle handling and transport of the pigeons, so I was wondering if the sportsmen feel anything, such as gratitude, towards them.

The hawk has to eat once a day at sunset and it cannot eat on the ground except when there is a particular situation as in the plane scene, but it is better if the falcon eats while flying. The pigeon is the best prey to give to a hawk. The falcon is the animal that flies the highest and the only one who can stare at the sun. This means that a man who owns a hawk is closer to God. They feel a sense of enormous gratitude for all that the hawk means symbolically. The European falconers believe that you should not touch the hawks because they are plumed animals but the sheiks love them too much and they want to live very close to them.

Falconry is a tradition that dates back many years in the Arab culture. Are the new generations of young people embracing it and keeping it alive?

Qatar, before discovering gas, had nothing except their tradition of desert life. For them, tradition is everything and in fact for me, this is not a film about falconry but on traditions in modern times. A child becoming a falconer represents the passage into adulthood.

In general terms, can you talk about your process of putting a documentary together from the moment you decide on a subject? When does the musical score come about? The music in The Challenge is quite a force.

In general terms, can you talk about your process of putting a documentary together from the moment you decide on a subject? When does the musical score come about? The music in The Challenge is quite a force.

I am the least appropriate person to answer this question because the way I work is completely wrong. I don’t have a precise script but I start with an image I have seen or an intuition. I find myself very often in surreal situations that I live intensely and I try to shoot in that moment and I try to transmit the same feeling to the viewer. While I am shooting, I start to mentally edit and I share my view with my sound engineer, who is blind and he is always with me during the construction of the film. For me the sound is the screenplay of the movie.

Yuri Ancarini has several upcoming screenings in major North American cities. Check the graphic for a location near you. Many of his works are also available on his Vimeo Channel (https://vimeo.com/user7922709). We’ll keep you updated on the availability of The Challenge. In the meantime, click here to check out the official trailer.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian