Since both my driving and language skills are severely challenged in Italy, I always hire Marcello, a driver/interpreter, when I’m researching a new novel. A few years ago, Marcello and I were speeding along the highway hugging the western bank of the Serchio River north of Lucca when we saw a mammoth stone footbridge at Borgo e Mazzano. Its beautiful humpback shape was obviously the work of many experienced craftsmen.

“Wow! What’s that?” I asked.

“The Ponte della Maddalena,” Marcello said. “But nobody calls it that. It’s Ponte del Diavolo.”

The Devil’s Bridge?

With a straight face, Marcello went on to tell the story.

Sometime in the Middle Ages, he said, a master builder was contracted to build a new bridge across the Serchio, a lovely winding river that flows through the mountainous region called the Garfagnana.

The builder’s work went slowly until he realized he could not make the villagers’ deadline. He was desperate.

Suddenly, a tall, well-dressed merchant appeared. The man said he could finish the bridge that night, under one condition: The builder had to give him the soul of the first living thing that crossed the bridge when it was completed. The builder agreed, and the next day the villagers had their beautiful bridge.

When they congratulated the builder, he told them to wait until he sought the advice of the local bishop.

“Fool the devil,” the bishop said. “Send a pig across first.”

The builder found a pig and let it cross. Furious that he had been tricked, the devil threw himself into the Serchio. Today, there are those who insist that a green shadowy figure is visible just below the surface on All Souls Day.

“The Devil’s Bridge?” I wondered.

“Well,” Marcello said, “remember this is the Garfagnana.”

I didn’t realize what that meant until I learned that this region has a well-earned reputation for strange and unexplained happenings. Stretching between the Apennines to the east/northeast and the Apuan Alps to the west, it is marked by towering mountains, some brilliantly white, others deeply forested, abandoned “ghost” villages and bubbling streams. Often, heavy mists cover the countryside.

I learned, for example, that Mount Matanna is a favorite haunt for witches. An odd-shaped rock is said to be used as a table for their magic and to sacrifice victims. It’s also said that a ghost holding a scythe guards a tremendous treasure hidden in the mountain.

And people swear about what happens in the Grotta del Vento, a system of caves and grottos at the tiny village of Fornovalasco, north of Gallicano. After passing a glass case that contains bones of an 8,000-year-old cave bear, you’re in a completely dark room. Although no one speaks, you can hear voices. Speleologists explain that the sounds are caused by drops of water, but who could ever believe speleologists?

One day, Marcello greeted me with: “Let’s go visit the ghost town.”

Why not?

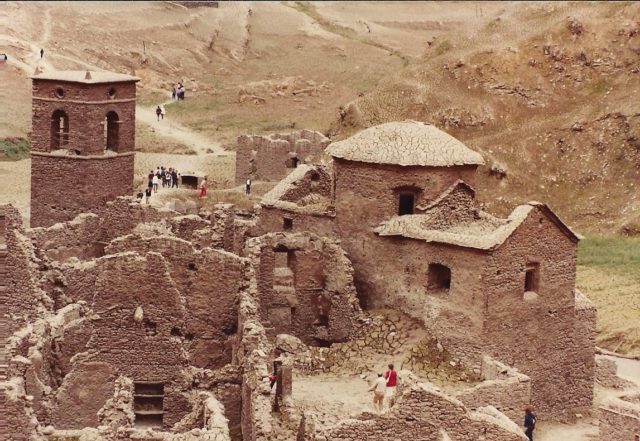

There was, he said, a town called Fabbriche di Careggine near Castelnuovo di Garfagnana. When a hydroelectric dam was built after World War II, a huge man-made lake was formed. In order to create the lake, Fabbriche di Careggine had to be flooded and its residents moved to the nearby town of Vagli Sotto.

Periodically, the lake is emptied and people can walk in the mud and see the remains: stone buildings, a church and bell tower, a bridge, a cemetery.

Some people call it Paese Fantasma, the ghost village, and they say spirits have been seen and strange events have occurred since the old village was flooded. On cold winter nights, it is said, the bells can be heard, even though they were removed long ago.

We visited the lake but only saw water. And yet. Could that faint sound we heard have been bells?

The above appears in the August 2019 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian