Columbus’ voyages challenge our concept of history.

On the one hand, we have the heroic notion of Columbus sailing the ocean blue to discover a new world. On the other, we have the revisionist interpretation of Columbus as a perpetrator of genocide. In between is a full range of facts, questions and interpretations that make history the fascinating discipline it is.

First and foremost, Christopher Columbus was a man of his times. And like all of us, he was an imperfect mortal. He embodied the spirit of enterprise then emerging in Europe, but his pursuit of material gain had a devastating ripple effect on the native nations. In short, his strengths and weaknesses were those of the culture he represented.

Columbus’ unique nautical expertise made it possible for him to reach the Americas, and after his triumphant return, human history would never be the same.

The new world he helped create was a global entity where no group could for long remain isolated. It paved the way for the world we know today, which has been repeatedly made smaller by such inventions as the telegraph, internal combustion engine, telephone, radio, TV, satellites, internet and cellular devices.

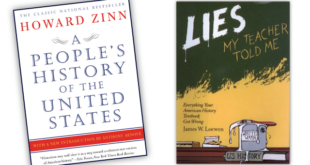

Consideration of Columbus’ image reminds us that history depends on who’s writing and reading it. With the explosion of information triggered by Columbus’ voyages, the body of history has evolved over the centuries into a dialogue between what our ancestors wanted to preserve and pass on to us and the information we now seek to make the past relevant to our times.

History doesn’t change — it’s happened, it’s gone — but our view of what’s important or irrelevant, noble or reprehensible, stylish or base, does.

And the way history is processed changes with each generation, too. The political, military and biographical approach that seemed so complete to historians of the past has shifted to a more sociological paradigm that focuses on the people — all of the people — men, women, families, workers, and class and racial groups. And that approach will no doubt give way in time to other schools of thought.

History bestows identity. Whether it be the narrative of our family, tribe, city, state, nation, race, gender or class, it supplies us with the information and inspiration we need to define ourselves as individuals and groups.

Thus, the image of Columbus at different times has been used to promote a sense of American exceptionalism and American individualism.

The 400th anniversary of his first voyage to the Americas was the occasion for a World’s Fair in Chicago. Italian immigrants to America embraced Columbus as a way of laying claim to respectful treatment in their new land. Catholic men have used his image to inspire the works of the Knights of Columbus, while Native Americans have often seen Columbus as a symbol of the maltreatment of their people.

We can, and should, disagree about our interpretations of the past. There are no easy answers. Debate will sharpen our analytical skills and help us deal with the many problems and conflicts engendered by our diverse society. Hopefully, we’ll learn to not rain on each other’s parades in the process.

The value of individual persistence and the power of technical expertise are just two of the historical lessons we can learn from Columbus. But we also can learn that positive developments often have unintended negative consequences.

Above all, we can learn that cultural isolation is impossible. The real question is how to live harmoniously with the many cultures we encounter.

Columbus’ voyages brought together two continents to create a new world — our world — along with the myriad aftereffects of that historic event.

This is the spirit in which we should approach the perennial debate.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian