In her own unobtrusive way, Mom had long been preparing me for school. In a letter my grandfather wrote her from Italy when I was four and a half, he was glad to hear I spent entire days “writing.” He was referring to my filling a sheet of paper with rows of little vertical lines in imitation of the lines my mother had made on the page.

Now, a year and a half later, while she was reading her weekly letter from her father, I asked her whether it was hard to learn how to read.

“No, it’s not hard, Pierino. You’re going to learn when you start school soon.”

I doubted I could ever master that esoteric craft. The blue marks on the letter she showed me seemed an endless succession of random squiggles and indecipherable shapes. How would I ever learn to memorize them all, much less understand what they supposedly said?

“Don’t worry, you’ll learn,” she assured me. “And you’ll love it. Reading is the most beautiful thing in the world,” she said in Italian: “La lettura è la cosa più bella del mondo.”

On an early September morning of 1956, my mother and I walked the short block from our tenement to the squat, red-brick building of St. Rita’s School on 146th Street in the South Bronx. I couldn’t wait to begin populating my brand-new Composition Notebook with all those arcane signs.

Across the street from the school was a wide sidewalk fronting a line of trees and benches that functioned as the gathering place for us students in the morning and after lunch. Hordes of older kids — the boys in blue gabardine pants, white shirts, and blue SRS ties, and the girls in maroon jumpers, white blouses, and maroon berets — were already shrieking and chasing one another. Far from being a “whining schoolboy” that morning, I felt superior to several “babies” — my new classmates, no doubt — who were bawling with dread.

Meanwhile, a formidable-looking bunch of Dominican nuns and two female lay teachers had emerged from the school building and were moving toward the areas where their classes would soon be lining up. Last of all, a bespectacled and bottom-heavy old nun, Sister Eugene, our principal, hobbled out of the school with a ding-dong bell in her hand.

I had seen the drill several times before, when I happened to be there with Mom during the school’s lunchtime recess. Sister Eugene rang her bell lustily five or six times. All the kids fell silent and froze in place, stopping their speech in the middle of sentences, or even words, and locking their limbs in whatever position they had been at the first clang. Wherever I looked, kids stood on one foot or threw arrested punches at the empty air. Since I hadn’t been in motion at the time, I just stood there.

After holding us awhile in silent suspension, Sister Eugene rang the bell once to signal we should proceed to line up swiftly and silently. The girls stood in one line, with the boys right next to them, at predetermined sites for each of grades one through eight.

A tall, handsome young nun was waving the obvious first-graders toward her turf. She told us she was Sister Catherine Michael and that we should line up in size places. All of us began putting our hands up to our own and other kids’ foreheads to measure whose was higher up. As our new teacher shepherded our straggly line of tiny boys and girls toward the school, I stole a glance at my mother and caught her waving at me, flashing a triumphant smile.

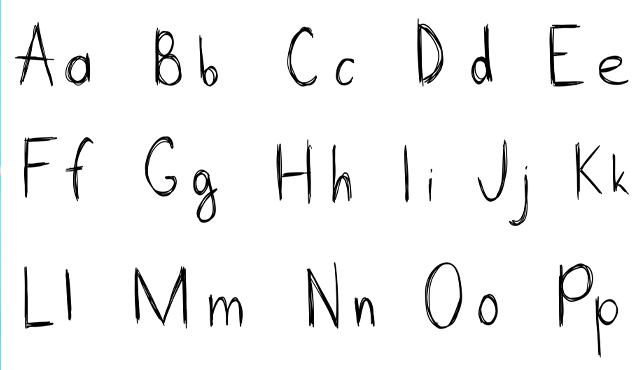

Upstairs, the first day’s lesson was on how to make a capital T. Sister Catherine Michael showed us on the blackboard how to form the letter in two easy strokes. Then she explained how to fold the first page of our notebooks so as to create four columns and told us to start making the Ts in our book on the side of the paper “by the window.”

She simply meant — for those of us who didn’t know left from right — the side of the page that was closest to the large window on our left. Accustomed to hearing mainly Italian at home, I didn’t understand her positional usage of “by,” so I drew the frame of a window around the first T that I inscribed on my page. In checking our work as she walked around the aisles, our teacher tapped on my “window” with her finger but didn’t say anything — perhaps not knowing what to say.

Although I went home for lunch, the afternoon seemed to drag, maybe because the entire time was taken up with learning how to make a capital H. Indeed, our first homework assignment was to make a whole page of them — four columns of capital Hs, each taking up two full lines in our notebooks, with a line skipped between each row.

That evening, I folded my notebook page but decided to expedite things by a clever ploy. I drew four sets of parallel lines all the way down the page and penciled in a horizontal cross-bar for each future H. Then I started erasing the superfluous pairs of short vertical lines that still joined all my letters in huge ladders of Hs. I soon panicked, though, realizing my attempted shortcut was quite obvious, since the lines I had practically engraved into the page were resistant to full erasure.

I called my mother over. “Look! The teacher’s going to see the mess I made!”

“Just rip out the page,” she said in Italian, “and start all over. And this time do it right.”

My mother was a genius. Her Gordian-knot-type solution hadn’t occurred to me at all.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian