Mired for months in the battle to take the Italian town due south of Rome, Edward Malatesta fought his way through Italy and France before mortar fire took him out of the war.

Edward Malatesta was born on Nov. 8, 1924, the youngest of five children and the only son of Alessandro and Gulia (Ragnetti) Malatesta. His parents immigrated to the United States from Senigallia, Italy, as a young married couple, first to Philadelphia and then to the Taylor Street Little Italy in Chicago. The family settled on the Northwest Side after Malatesta was born.

He has fond memories of Sunday family dinners. “My dad usually went down in the basement and made homemade macaroni, and that’s what we had,” Malatesta says. He also loved his mother’s meat- and spinach-filled ravioli. “I used to help my mother when she made raviolis,” he says. “I remember using a fork and closing them up.”

He attended Burbank Grade School and Washburne Trade School. After graduating in 1942, he worked in the machine shop at Continental Can. He was drafted into the Army in April 1943. “At that time, all my buddies were getting drafted, and it was kind of my duty to get in.” His parents worried about their only son. “My mother didn’t like it,” Malatesta says. “She wasn’t too happy about it, but I guess every other mother was going through it.”

Malatesta was inducted at Camp Grant, Illinois, and completed 13 weeks of basic infantry training at Camp Robinson in Little Rock, Arkansas. Soon after, he boarded the Louis Pasteur, a troop ship, and took off into the Atlantic from Newport News, Virginia. “We were all alone; we zigzagged,” Malatesta says. Seven days later, he arrived in Casablanca and boarded a train to Tunisia.

Malatesta deployed from Tunisia to Naples and was assigned to a replacement depot. He was then attached to the Third Division, Heavy Weapons Company, as a machine gunner. “The first night there, German planes came over, dropping bombs,” he says. “I jumped in a hole.”

From there, Malatesta moved up to Third Division Headquarters near the foothills of Cassino. Then, the strategy changed. “I was fortunate,” he says. “In a way, it was good for me because they took me up to the front lines, and about that time, the whole division left, withdrew.”

Malatesta’s unit returned to Naples for amphibious training, and in January 1944 headed off for the invasion of Anzio on LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry). “That was an experience,” Malatesta says. As No. 1 gunner, he carried the tripod for his 30-caliber machine gun. “We walked out into the water, and it was up to your chest,” says Malatesta. “I didn’t know what to expect.”

Meeting no resistance, the troops advanced about six miles and dug in, awaiting further orders. A day or two later, they began pushing forward and moved about 10 miles from the beachhead. That’s when the Germans attacked with shells, mortars and screaming mimis. The latter were rockets, shot in clusters, that got their name from the sound they made as they tore through the air. “They shoot them all at once,” Malatesta says. “They all came in — pop, pop, pop!”

The battle raged for months. “We were under fire all the time. You just think about staying alive. That’s about it,” Malatesta says. “You wish you were a little mouse when the shells come in, like you could crawl in a little hole.” The weather was cold and wet, and if a soldier dug a foxhole too deep, he reached water. “We would get the shell casings, cardboard, and we’d line the bottom of our hole because we stayed there for a long time,” Malatesta says.

The troops rotated periodically between the front lines and their “rest area” in a wooded spot near the beach. “We just went up and back,” Malatesta says. The fighting was horrific. He remembers a direct hit on a foxhole that his buddy was sheltering in. “You couldn’t see him,” he says. “Just blown to bits!”

Malatesta recalls the Battle of Cisterna di Lottoria. A Ranger regiment advanced to overtake the town and was surrounded by German troops. “They annihilated the whole regiment,” Malatesta says. Back in Naples, his buddy had volunteered for the regiment and wanted Malatesta to join, too. “So I could have been one of them,” says Malatesta.

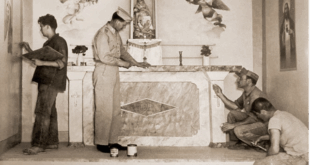

The Allies took Anzio at the end of May, and by June moved into Rome, where Malatesta spent a few days. He met up with a childhood friend, a military policeman, and they spent some time together. “Oh, it was great,” Malatesta says.

From Rome, Malatesta returned to Naples to prepare for the amphibious invasion of Southern France in August 1944. “There wasn’t too much resistance there, so we were lucky,” he says. Advancing through small towns, they ran into a big battle in Montélimar. The French blew out a bridge, and the Germans could not retreat. “We just annihilated them there,” Malatesta says. “It was a massacre.”

Malatesta’s unit advanced to St. Die des Vosges, close to the German border. “We went into this wooded area, and all of a sudden, they zeroed in on us,” he says. “We were shelled, mortared. We had no cover, just had to hit the ground, and suddenly I was hit in the arm with shrapnel!”

He was trying to get back to the command post when one of his buddies got hit around the eyes and could not see. As Malatesta went to help him, more shells came in, and he was hit in the leg. Wounded in his arm and leg, Malatesta struggled to bring his buddy back for help. The shelling continued all around them as they trudged about half a mile to the post. “I was thinking this is it,” Malatesta says.

He was taken to an evacuation hospital, stabilized, then flown to England where a doctor examined him and sent him back to the States. “Fortunately, I got a million-dollar wound,” Malatesta says. He shipped back on the Queen Mary, boarded a train in New York and, during a brief stop at Union Station in Chicago, visited with his parents before heading to Baxter General Hospital in Spokane, Washington.

Malatesta healed from his wounds and was assigned various duties, such as guarding German prisoners who worked on farms in Wisconsin and Illinois. Sergeant Malatesta was discharged in October 1945. Among his many medals are four Battle Stars and a Purple Heart.

He returned to Chicago and to Continental Can, where he worked days and attended Industrial Engineering College at night. He retired from the engineering department after 43 years. Malatesta married Melinda Catalo in 1947, and they had two daughters and six grandchildren. Now a widower, he has six great-grandchildren.

Malatesta reflects on the war. “When you’re in the infantry and you look around, they talk about this law of average thing, and you see that a lot of your buddies are gone, and you’re probably the oldest one in the group, and you figure, ‘Oh, oh, my turn is next,’ so you never know.” He concludes, “God Bless America!”

The above appears in the December 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian