Renowned throughout the world for her inspirational missionary work, St. Frances Cabrini had a special place in her heart for the Windy City.

St. Frances Xavier Cabrini is revered in Catholic circles for her holiness and fervent devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and she is known throughout the world for establishing dozens of hospitals, schools and orphanages in 16 countries. Although her work spanned two continents, Mother Cabrini had a special connection to Chicago, tirelessly serving the immigrant Italian community there for decades and eventually passing away in a hospital she helped to create. A U.S. citizen since 1909, she was the first American to be canonized, but she never lost her italianità. That’s not surprising, since she didn’t leave her native Italy until she was 38 years old.

Cabrini traced her roots to SantˊAngel Lodigiano, a small town in the province of Lombardy, about 20 miles from Milan. Born Francesca Saverio Cabrini on July 15, 1850, she was affectionately nicknamed Cecchina, or little chickpea, because she was so small. She worked on a farm and was educated at home by her older sister.

Despite being sickly from the time of her premature birth, Cabrini studied hard and became a teacher. She developed a lifelong fear of water at the age of 7 when she fell into the Venera River and almost drowned during a visit with relatives. Overcoming that obstacle, too, she made more than 20 transoceanic voyages during her far-flung undertakings.

From an early age, Francesca Cabrini was fascinated by missionaries, especially St. Francis Xavier — from whom she would take her religious name — who wrote about his experiences while spreading the Word of God in the Far East. These stories inspired Cabrini to pursue a vocation as a missionary to China, but she was rejected by existing religious communities because of her poor health. Cabrini was undaunted, and her ardor was eventually recognized by a local bishop, who encouraged her to start her own religious community.

At the age of 30, she did exactly that, naming her community the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. This came at a time when missionaries were almost exclusively male. The rules that Cabrini wrote for her new sisterhood emphasized charity above all else, followed closely by obedience and prayer. Perhaps her best-known motto came from Philippians, 4:13: “I can do all things in Him who strengthens me.”

When Cabrini met with Pope Leo XIII in 1889, he told her to go “not to the East, but to the West,” specifically to New York to tend to the countless Italian immigrants there.

While Cabrini has often been honored, few titles are more appropriate than the one bestowed upon her by the American Committee on Italian Migration, which in 1952 named her the Italian Immigrant of the Century.

Cabrini began her own experiences as an immigrant at age 39 in 1889, when she departed for New York aboard the Bourgogne on the first of many trips across the Atlantic. During the voyage, she and six companion sisters traveled in second class while offering comfort and aid to the less fortunate aboard the ship, among whom were 1,500 other Italians. Those most in need traveled in third class, which the sisters described as “no better than a stable.” Their taxing journey took 12 days.

When Cabrini landed in New York, her prospects for success seemed as slender as she was. A frail woman with neither money nor powerful connections, she possessed only a modest command of the English language. What’s more, it turned out that the house promised to Cabrini and her sisters in New York was a “pious exaggeration.” (In other words, it didn’t exist.) Instead, they found a place to live in the heart of the Italian ghetto. Despite the odds, it wasn’t long before Cabrini established an orphanage and a school.

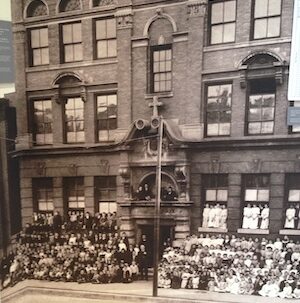

Circumstances then sent Cabrini down a path filled with twists and turns that eventually led her to Chicago. There, she founded and then taught at the Assumption School for Italian immigrant children. Originally located at 317 W. Erie St., it opened in 1899 with 500 students. Upon Cabrini’s insistence, this school, like many others she and her sisters ran, was free of charge.

The needs of her fellow Italians in Chicago grew along with their population, which rose from 5,700 in 1890 to 16,000 in 1900 and 45,000 in 1910. Like so many other immigrants, they lived in vastly overcrowded housing and labored for meager wages. Uncharacteristic of the times, Cabrini encouraged her sisters to teach young women the industrial arts so they could support themselves.

At the time, there were very few government or philanthropic agencies that advocated and cared for Chicago’s Italian immigrant community. Cabrini’s first impulse was to establish an orphanage, but the newly appointed archbishop, James Quigley, asked for a hospital instead. He had one in mind that was for sale.

After inspecting it, Cabrini decided to look for something better. Soon, she found the six-story North Shore Hotel in Lincoln Park, which was also for sale but at a much higher price. Since Cabrini had only $1,000, she turned to Archbishop Quigley for a decision. He selected the property Cabrini favored, which left her with the challenge of raising the significant sum of $25,000. She succeeded.

Cabrini had organizational skills to match her talent for fundraising. Further, she developed a sharp business sense. For example, in purchasing the site for the hospital, Cabrini suspected the sellers were being dishonest in stating the property’s measurements. One morning at daybreak, Cabrini and her sisters tied shoestrings together to create a makeshift tape measure. Sure enough, they discovered mistakes. Faced with the facts, the sellers made the corrections and adjusted the price.

There were more challenges ahead in the creation of the hospital. The contractors who were hired to do the remodeling stole materials, ran up a huge debt and demanded payment to continue the work. Cabrini filed a lawsuit and succeeded in getting the contract canceled. Then, she took on the task of supervising the work, hiring unemployed laborers and enlisting the help of her sisters to complete the renovation. In 1905, Columbus Hospital opened.

Cabrini took great pride not just in renovating the building but also in offering quality health care. To that end, she sought professional staff and the best and latest equipment. Columbus Hospital emerged as a preeminent health care institution in Chicago, remaining so for nearly a century.

A report sent to Rome by the sisters in March 1913 provides insights into Cabrini’s philosophy. It noted that Columbus Hospital annually cared for 1,400 patients, “accepting not only Italians, but Slavs, Poles, Germans and Spaniards.” The report also noted that the sisters who taught in the hospital’s school of nursing provided spiritual guidance as well as medical instruction, allowing the nurses to “offer the comforts of religion as well as the care of the body.”

Cabrini next turned her attention to the health care needs of the teeming Italian enclave on the city’s Near West Side. Securing an appropriate building and making the necessary alterations, the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus opened the Columbus Extension Hospital in 1911, offering free care to the Italian community of the Taylor Street neighborhood. Later renamed St. Cabrini Hospital, it remained open until 2001.

In 1917, Cabrini purchased a 102-acre farm in northwest suburban Park Ridge, near Northwest Highway and Dee Road. Anticipating wartime shortages, she planned to supply fresh milk, eggs, and chickens to her hospitals and other institutions. She also hoped to use the property as a possible site for a school, orphanage or hospital.

Cabrini’s impact on the Italian community extended well beyond bricks and mortar. She would walk the streets of the Italian areas, consoling families and delivering a message of faith in God. She and her sisters taught catechism at area parishes with large Italian populations. Among them were St. Philip Benizi, which was opened in Little Sicily on the city’s Near North Side in 1904.

The children in those catechism classes referred to their teachers simply as “le sisters,” while Cabrini’s fellow sisters regularly called her “La Madre.” Many in the Italian community addressed her simply as “Madre Cabrini.”

As the decades went by, Cabrini’s influence spread across North, Central and South America. She and her sisters established 67 missions in U.S. cities like New Orleans and Seattle, as well as in Central and South American countries like Nicaragua, Brazil and Argentina.

Despite her far-flung efforts, Chicago remained Cabrini’s spiritual and physical home. She passed away in her beloved Columbus Hospital on Dec. 22, 1917. Beatified in 1938 and declared a saint in 1946, she was formally proclaimed “Patroness of Immigrants” in 1950. Her feast day is Nov. 13.

Cabrini’s strong links to the city are confirmed by her inclusion in the book “Chicago and the American Century, The 100 Most Significant Chicagoans of the Twentieth Century” by Richard F. Ciccone.

On the occasion of her beatification, Chicago Archbishop Cardinal George Mundelein underscored the Chicago bond, saying, “I knew Mother Cabrini very well. I was the last one to whom she spoke outside the nuns of her own community. I celebrated the Pontifical Mass at her funeral (in the chapel of Columbus Hospital).”

On the day of her canonization in Rome, a special candle with her picture was presented to Pope Pius XII by Monsignor George Casey of Chicago, who helped advocate the cause for her canonization. On WGN Radio, Chicago’s archbishop, Samuel Stritch, said, “Today, we pray to her and beg her to be the special patron of Chicago. She loved Chicago. She served Chicago’s best interests. She is a benefactress of Chicago.”

The Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus continued Cabrini’s work in the city long after her death, opening the Frank Cuneo Memorial Hospital in the Uptown neighborhood in 1957.

Cabrini was so well known locally that at one point she became the unofficial patron saint of parking spaces, with Windy City residents chanting, “Mother Cabrini, Mother Cabrini, please find a spot for my little machiney,” as they searched for a spot.

Cabrini has been honored in numerous ways across the country and beyond since her passing. There are statues and shrines dedicated to her at the base of the Statue of Liberty, at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., and at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. Her image can be found on an Italian postage stamp issued in 2016 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of her canonization. And she is listed in the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.

Here in Chicago, the Cabrini Townhomes were built in 1942 in the neighborhood around Division Street and Clybourn Avenue, where many immigrants from Lucca lived and worked in nearby plaster shops.

In the early 1960s, Chicago’s Little Sicily was plowed under to make way for a large, high-rise public housing complex that came to be known as Cabrini-Green. A source of affordable housing for more than 15,000 residents at its peak, it devolved into a magnet for crime, with the last of the high rises being demolished in 2011.

In the Taylor Street neighborhood, where Cabrini had such a huge impact, a short street just west of the University of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus bears her name.

In 1955, the National Shrine of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini was created to celebrate her life and accomplishments. Originally constructed as a chapel inside Columbus Hospital, it became a center of worship and prayer for patients and staff.

The shrine and hospital closed in 2002, but when the building reopened as luxury residences in 2012, a remodeled shrine also reopened to serve as a spiritual center and “a symbol of the great work and mission of a remarkable woman.”

The shrine’s main altar features a glass case containing St. Cabrini’s humerus, and above that are stunning frescoes depicting different stages of her life. The room where Cabrini died has been preserved and is currently on exhibit inside the shrine.

In October 2022, a new statue of Cabrini was unveiled in the courtyard of Holy Name Cathedral at State Street and Chicago Avenue, and a bas-relief reliquary was mounted inside the Cathedral. (Turn to page 59 for details.)

The groundbreaking nature of Cabrini’s accomplishments can’t be overemphasized. The Milan Catholic magazine pointed out that Cabrini’s title of “missionaire” (the feminine form or missionary) was a new term that didn’t exist in any dictionary at the time.

Cabrini never wavered in her commitment to social justice, despite the many challenges she faced in staring down prejudice and sexism, coping with a frequently skeptical clerical world and constantly raising money while navigating rough-and-tumble local politics. In an attempt to find the right word to encompass Cabrini’s diverse skills in the public arena, one Italian minister described her as a “statesman.”

Her achievements are sometimes attributed to her fast pace, but hers was not the sort of high-octane energy that fuels much of secular ambition. Rather, Cabrini exuded an inner calm and was known for her dignified demeanor. She once wrote: “Give me your grace, most loving Jesus, and I will run after you to the finish line, forever. Help me, Jesus, because I want to do this with burning fervor, speedily.”

While Cabrini was surrounded by people throughout her life, she found solace in solitude and was content to be alone. The story is told that she asked to be left by herself in her last hours.

Viewed from a distance, Cabrini appears quite ordinary, down to the simple veil she wore as part of her habit. Upon closer inspection, though, the veil revealed a checkerboard pattern that was quite delicate, intricate and beautiful. That veil can be seen as a metaphor for her multifaceted nature and career.

The above appears in the March 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Check out the sensitive and topical 50-minute documentary, titled “Frances Xavier Cabrini: The People’s Saint”.

Written and Directed by two-time Vatican Film Festival winner, Lucia Mauro, the documentary explores the environment and deep spirituality that shaped Mother Cabrini.

It includes enlightening interviews with author-scholar Achille Mascheroni, Sr. Joan McGlinchey, MSC, Sr. Bridget Zanin, MSC, Father Richard Fragomeni, artist Meo Carbone, architect Christopher Payne, Sr. Maria Regina Canale, MSC, youth ministers from the Archdiocese of Chicago, and new immigrants establishing strong faith communities. With a special appearance by Il Grande Coro di Roma, conducted by Fabrizio Adriano Neri and filmed live in Rome performing an original hymn composed by Enzo De Rosa exclusively for this film.

The film was chosen as an Official Selection at the 2018 Catholic Film Festival in Seoul, South Korea, and broadcast in its entirety by the Catholic Peace Broadcasting Company, Korea’s major Catholic TV Channel.

The film is available to rent on Vimeo in five languages: English, Italian, Spanish, Polish and French.