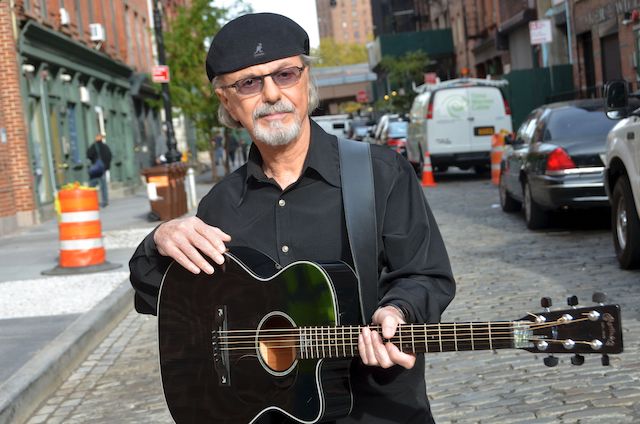

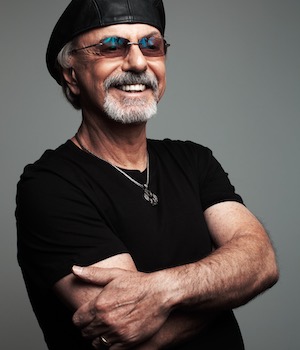

One of the last great performers from the golden age of rock ’n’ roll, Dion DiMucci has recaptured the spotlight by embracing his musical roots.

Dion DiMucci is a living legend known worldwide for hits that span decades and generations, like “Teenager in Love,” “Runaround Sue,” “The Wanderer” and “Abraham, Martin and John.” One of the last great performers from the golden age of rock ’n’ roll, DiMucci is still playing and recording at age 82. On his most recent release, “Stomping Ground,” the rock hall of famer is joined by Bruce Springsteen, Joe Bonamassa, Peter Frampton, Mark Knopfler, Billy Gibbons, Eric Clapton and many more. Speaking with DiMucci, you soon realize why so many of these renowned artists are willing to bestow their talents in tribute to this man, who is not only an oracle of pop music, but also of life itself.

DiMucci, known to legions of fans simply as Dion, was born in the Bronx, New York, in 1939.

“My parents were second-generation Italian,” he says from his winter home in Florida. “My grandparents came here in 1906 and 1909. As a child, I spent a lot of time with my grandfather. He used to take me to Manhattan, and on the way there, we would go by the Statue of Liberty. We would stop, and he would tell stories of how he arrived in America and what the statue represented to him. He also used to say there should also be one on the West Coast to welcome the immigrants who came in from there.”

DiMucci grew up in the Little Italy section of the Bronx and experienced firsthand the positive and negative effects of living in an urban, ethnic enclave.

“It was a rough neighborhood. Guys were always fighting. There were gangs. Jake La Motta used to walk the streets,” says DiMucci, who still has a thick New York accent. “But there was also culture nearby. My grandfather used to take me to the opera at the Windsor Theater near Fordham University, which was only a couple blocks from my house. I heard ‘La Traviata,’ ‘Pagliacci,’ Puccini arias. It was so thrilling.”

Even though he was deprived of a formal education, his grandfather was a well-informed man and impressed upon the future singer the value of lifelong learning.

“He was constantly reading books, newspapers,” DiMucci says. “And he stressed the same for me. Every morning before school, he would make me zabaglione, cracking two eggs and beating the yolks for 20 minutes. He would say, ‘Eat this. It’s brain food.”

DiMucci’s grandfather played a major role in his upbringing, not only because of the example he set, but also because of the amount of time he was able to spend with him. Opening up on a personal subject, DiMucci talked about the dramatically different relationship he had with his father.

“My father had the mind of a 13-year-old. He had no job and really couldn’t support us,” DiMucci says. “But he was an interesting man, and I treasure the time I spent with him. We used to go to the park, lie on our backs in the sun, and he would pick up a leaf and tell me what tree it was from and show me the veins in the leaf. During the summer, we would go swimming at Orchard Beach, sometimes naked, and we would always go to the Bronx River to look at the waterfall, or the Bronx Zoo. We lived a block from there, and together we saw every animal imaginable.”

DiMucci developed a love for American country music, specifically Hank Williams. By the age of 12, he learned to play all of Williams’ hits just by listening to his records. As a teenager, he started making money singing Williams’ songs in bars and even sang “Jambalaya” on Paul Whiteman’s radio show.

But it was doo-wop that propelled DiMucci to fame. He and his friends cut the classic figure of guys standing on a street corner, warming their hands around a garbage can fire and conjuring a capella harmonies out of thin air.

“It was me, Carlo Mastrangelo, Angelo D’Aleo and Fred Milano,” DiMucci says. “We were all street guys, so we called ourselves Dion and the Belmonts after our neighborhood in the Bronx.”

With hits like “Where or When,” “I Wonder Why” and “Teenager in Love,” the group was an immediate success. They began appearing and touring with many big stars, including Bobby Darin (Walden Robert Cassotto), who also grew up in the Bronx and took DiMucci under his wing. In time, DiMucci met a Texan by the name of Buddy Holly.

“We used to run into each other all the time in New York, through events like the Alan Freed show, and he began to like it there,” DiMucci says. “In fact, he married a Puerto Rican woman, Marie Elana, who lived in New York, and they got an apartment near Gramercy Park in the Village. I started to show him around. I introduced him to Manny’s Music Store, Phill’s Men’s Store, egg creams and Parmesan cheese. One day he told me, ‘You know, I’m just a hick from Texas. I had never had Parmesan cheese before. In fact, I don’t think I ever saw an Italian.’”

In February of 1959, the Belmonts were asked to tour with Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper as part of the “Winter Dance Party.” Exhausted and worn down by freezing-cold buses, Holly decided to charter a plane. DiMucci was asked to join them on the flight and related his answer on National Public Radio.

“He (Holly) said, ‘You know, it’ll be $36 (per person for the flight),’ and he hit the magic number. I grew up with my parents screaming and yelling at each other for the rent. At the time, it was $36. My mind hadn’t stretched out to that place where I could spend a whole month’s rent on a 45-minute plane flight, so I said no.”

The plane crashed, killing all on board: a tragic event Don McLean immortalized as “the day the music died” in his 1971 hit “American Pie.”

DiMucci had been a heroin addict since age 15, and the tragedy made matters worse, so he checked himself into a hospital for treatment in 1960. After emerging clean and sober, DiMucci went solo, and his career exploded. His “Runaround Sue” hit No. 1, and a year later, “The Wanderer” made it to No. 2. More hits followed, including “Donna the Prima Donna,” with a version sung in Italian. In 1962, he was on top of the world.

The next year, the “British Invasion” swept America, cooling DiMucci’s solo career. A short-lived reunion with the Belmonts didn’t catch fire, either.

“I was with Columbia, which was then run by Mitch Miller, who was kind of an old fogie, and they didn’t know what to do with me,” DiMucci says. “I was being paid $100,000 a year to sit in a room and play piano with Aretha Franklin. They wanted to make, of all things, an album of Al Jolson songs.”

In 1968, however, he released “Abraham, Martin and John.” Recorded shortly after the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., the song captured America’s overwhelming grief. Versions by Bob Dylan, Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson, Ray Charles, Harry Belafonte and Whitney Houston have enshrined the song as an emblem of an era.

During that second phase of his career, DiMucci found his way back to his musical roots, which extended far deeper than country music.

“I started to get into blues when I was 17, listening to people like Jimmy Reed, B.B. King, and the Chicago guys like Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters,” DiMucci says. “But then I got hooked up with the Belmonts and made all these records, and I sort of forgot about it.”

In 1966, after John Hammond had taken over Columbia, DiMucci recorded an album of blues standards that didn’t earn a major release. In the ensuing decades, his life and career went through many changes, including reunions with the Belmonts, a religious conversion and induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1989.

DiMucci kept playing and performing, and in 2006, he recorded “Bronx in Blue,” an album of blues standards that was nominated for a Grammy Award.

“It’s the shuffle thing; I got it in my bones,” DiMucci says. “Lord, that sound! The beat, the chord structure — it’s in my DNA.”

In recent years, DiMucci has recorded a number of blues-oriented albums, including “Blues with Friends” and the single “New York is My Home” with Paul Simon from 2015. His latest release, “Stomping Ground,” represents yet another chapter in his legendary career.

The recording opens with the searing guitar runs of Joe Bonamassa, whose label, Keeping the Blues Alive, released the project. “Dancing Girl” features Mark Knopfler’s trademark sparse licks to a rhumba-like beat. “If You Wanna’ Rock and Roll” is another straight-head blues track featuring Eric Clapton. On “There Was a Time” with Peter Frampton, DiMucci looks back on his life and youth. Although the lyrics come straight from the heart, that’s not what captures DiMucci’s imagination.

“My God!” he bellows. “Did you hear Peter Frampton playing slide? That guy killed it!”

But it is “Angel in the Alleyways” that makes this album extra special. Featuring haunting harmonies by Bruce Springsteen and Patty Scialfa, the lyrics sum up the life of a man who was born in the Bronx and carries the neighborhood with him to this day. At 82, DiMucci is a legend, an oracle and a force still to be reckoned with in rock ’n’ roll. As the notes on the album say, “Dion is like a circling star that never fades, continually generating the energy and force we need to pull ourselves up and start again.”

The above article appears in the March 2022 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian