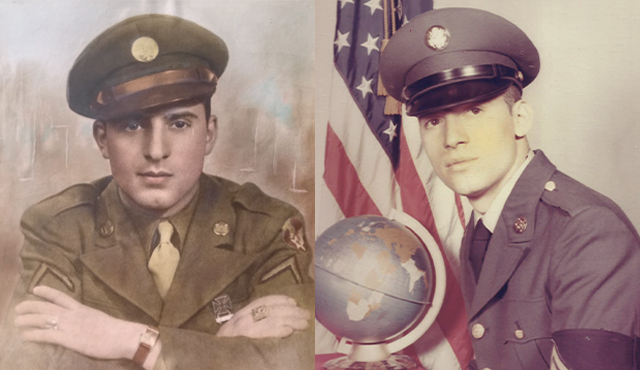

Though only 2 years old when his father, Joseph, was killed in action during World War II, Anthony Siciliano’s life was profoundly shaped by his dad’s bravery and sacrifice.

Anthony J. Siciliano was born in Chicago on Nov. 9, 1942, to Joseph and Mary (Parise). His maternal grandparents emigrated from Sicily, and his paternal grandparents from Naples and Calabria. The extended family lived in the predominantly Italian neighborhood surrounding Taylor and Halsted streets.

World War II raged on, and shortly after Siciliano was born, his father deployed to the South Pacific, where he built air strips and roads as a member of the U.S. Army’s 1896th Engineer Battalion. Siciliano remembers his grandparents pushing him in a stroller through the neighborhood. “We, of course, had the Blue Star flag in our window, and it seemed like every home had a Blue Star flag in the window. It is so vivid in my mind; I could see that right now,” he says. His father drew pictures in the letters he sent home. “There wasn’t a day gone by that they didn’t talk about my dad.”

One day, there was a knock at the door, and there stood a man in uniform holding a telegram. Joseph P. Siciliano was killed in action on Jan. 12, 1945, in Manila. Bursting into tears, his mother grabbed Anthony, and they huddled with his grandmother, sobbing. “I was old enough to know. It still chokes me up,” Siciliano says. “In thinking, talking about it, I could relive it all over again.” A letter arrived later explaining that Pfc. Joseph P. Siciliano was in a convoy, preparing to leave Manila, when it was attacked by kamikazes. He was awarded two Bronze Stars and the Purple Heart.

Siciliano and his mother were fortunate to have the love and support of grandparents and other family members as they struggled to cope with the tragedy. They always referred to his dad as “your father, the hero.” The family gathered together on Sundays to enjoy Grandma’s homemade meatballs, sausage and pasta. Ravioli was a specialty. “I remember them gently laying them out across a massive bed: a white sheet covered with all these raviolis,” Siciliano recalls.

He attended Holy Angels Grade School until his mother remarried, and the family moved to the neighborhood near Irving Park Road and Cumberland Avenue. Siciliano considers his stepfather, also a World War II veteran, a treasure in his life. “He made sure at every turn that I knew who my father was,” he says. Every Sunday, they ate dinner at his maternal grandparents’ house, then visited his paternal grandparents and often his stepfather’s parents. “My stepfather’s parents treated me like gold,” Siciliano says.

After graduating from St. Francis Borgia Grade School and Notre Dame High School, Siciliano worked as a hairstylist. He was living at home in 1963 when a former soldier his dad had served with visited them. “Somehow, by the grace of God, he tracked my mother down,” Siciliano says. From this stranger, they learned about his father’s fateful last day.

The soldiers were boarding a ship to come home when it was hit by a kamikaze plane and burst into flames. Siciliano’s father grabbed his buddy and pushed him out of harm’s way. Siciliano barely managed to swim ashore, where he died of his injuries. The man standing before them was the buddy whom Siciliano’s father protected. “He credited my father with saving his life,” Siciliano says. He and his family were thankful to hear the story. “To my mother, I think it was closure,” says Siciliano. “For me, he was my hero. Always was.”

Siciliano was drafted into the Army in 1964. His mother and stepfather offered to inquire about a deferment since his father had been killed in action. “I said, ‘No, I’m drafted, I’m going,’” Siciliano says. “It was another way to honor my father.”

He attended basic training, advanced infantry training and culinary school at Fort Knox, Kentucky. His orders took him to Selfridge Air Force Base in Michigan, where he cooked for Air Force personnel. While stationed there, Siciliano was promoted to Corporal. The mess hall was open 24/7 because pilots came in and out at all hours. “If they came in at 3 in the afternoon and wanted breakfast, it was there. If they wanted dinner, it was there,” says Siciliano.

Next, he transferred to Henry Kaserne Base outside of Munich, Germany, with a combat infantry unit in the 24th Infantry Division. “We were constantly playing war games, constantly in the field,” he says. Siciliano and the other cooks converted a 2.5-ton cargo truck, known as a deuce-and-a-half, into a kitchen. They prepared meals such as beef stew and corned beef hash with C and K rations left over from World War II and the Korean War.

Loaded up with coffee and cigarettes, Siciliano and an officer occasionally commandeered a jeep, slipped into surrounding towns, and secretly traded their rations for onions and potatoes. “Whatever we could get our hands on,” Siciliano says. “These little towns ate that up: American cigarettes!”

After his tour of duty, Specialist 5th Class Siciliano returned to America, mustered out in New Jersey and flew into O’Hare Airport. Antiwar demonstrators crowded the area. “They did not treat us well at all,” says Siciliano. “It didn’t matter (where you served), Vietnam was going on.”

A demonstrator pushed him, and Siciliano, young and short-tempered, lit into him. He looked up to see Chicago and Military Police officers approaching him. Suddenly they turned and walked away. “I got in a cab and came home,” Siciliano says. “I felt as if I were in a foreign land … this was not the America I left,” he recalls. Before, if he was in uniform eating out with his parents, somebody invariably would pick up the tab. “When I came home, it was a whole different experience,” says Siciliano.

During a successful post-service career as a hairdresser, he owned three salons and worked for a time at the corporate level with Hair Performers.

Ever an advocate for veterans and their rights, Siciliano actively participates in the American Legion. “I do it to honor the memory of my father and my stepfather, because I know they are in the trenches with me and others that share in the battle for the rights of all veterans,” he says. Siciliano is currently the Commander, House Manager and Post Agent of Post 974 in Franklin Park. He previously served as Commander of both the 9th District and 1st Division of Cook County, and Aide to the Department of Illinois Commander.

Proud to have served his country, Siciliano says, “It’s given me the ability to relate to perhaps some of the things that he (my father) experienced. But, then again, he was in the middle of a war.”

Losing his father at a young age was devastating. “Having the good fortune of knowing my father through my mother, my grandparents and even my stepdad was a bonus,” Siciliano says. “My dad, my hero! How my life would have turned out had he lived, I don’t even question it. I don’t know.”

The above appears in the July 2020 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian