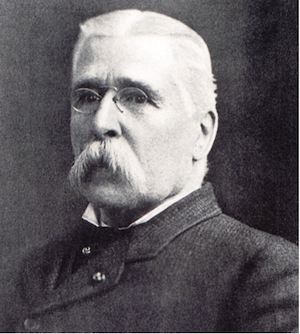

The first Italian American to earn the Medal of Honor, Luigi Palma di Cesnola was instrumental in establishing the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Cavalliere Emmanuele Pietro Paolo Maria Luigi Palma di Cesnola would never be mistaken for the “Modern Major General,” Gilbert and Sullivan’s satirical take on the overly educated officers of 19th-century England. While Cesnola didn’t know everything “vegetable, animal and mineral,” he knew enough about the martial, pedagogical and archeological to more than get by.

Cesnola led an amazing life, fighting wars on three continents, marrying an American blue blood and conducting groundbreaking archaeological digs in Cyprus. Born near Torino into a military family of lesser nobility in the Kingdom of Piedmont in 1832, he was the second son of a count and countess. Given the laws of primogeniture, which dictate the first son inherits the title, he had to make his own way in the world. After being kicked out of a Jesuit elementary school, he went to military school. As rebellion swept through Europe in 1848, young Luigi joined the fight to free Northern Italy from the shackles of Austro-Hungarian rule. (See page 39.) He fought with distinction, receiving the silver medal for bravery and was promoted to under-lieutenant at the age of 16.

After the war and his commissioning as an officer, Cesnola attended Piedmontese military academies, including the cavalry school at Pinerolo, and for several years, enjoyed the life of a young, handsome cavalry officer. Strangely, he resigned his commission and became an aide to several Italians fighting alongside the British in the Crimean War. Among those Italians was Sicilian General Enrico Fardella, who was serving with the British army in Crimea after being exiled by the Neapolitan Bourbons for his role in the Sicilian Revolt of 1848. Some writers surmise that, given Sardinia’s later involvement in the Crimean War, Cesnola may have been placed there as a prelude to Piedmont sending troops to aid the British and French and their Turkish allies in the conflict with Russia. Other writers with a more romantic turn of mind say Cesnola stopped serving the House of Savoy due to a love affair. Cesnola may have been present at the battle of Balaclava and was surely at the siege of Sevastpol. His experience with the Turks would serve him well much later in his life.

After the war and his commissioning as an officer, Cesnola attended Piedmontese military academies, including the cavalry school at Pinerolo, and for several years, enjoyed the life of a young, handsome cavalry officer. Strangely, he resigned his commission and became an aide to several Italians fighting alongside the British in the Crimean War. Among those Italians was Sicilian General Enrico Fardella, who was serving with the British army in Crimea after being exiled by the Neapolitan Bourbons for his role in the Sicilian Revolt of 1848. Some writers surmise that, given Sardinia’s later involvement in the Crimean War, Cesnola may have been placed there as a prelude to Piedmont sending troops to aid the British and French and their Turkish allies in the conflict with Russia. Other writers with a more romantic turn of mind say Cesnola stopped serving the House of Savoy due to a love affair. Cesnola may have been present at the battle of Balaclava and was surely at the siege of Sevastpol. His experience with the Turks would serve him well much later in his life.

After peace was declared in Crimea, Cesnola traveled to New York City around 1858 with a flute and not much more. He tried to make a living by teaching French and Italian and doing translations, but he barely scraped by, even after anglicizing his name to Louis. In April 1860, however, he had the great fortune to take in a new pupil by the name of Mary Jennings Reid, who was a member of the American aristocracy. One of her grandfathers was at the Battle of Lexington in 1775, and her father, Capt. Samuel Reid, was a hero of the War of 1812. (It was Reid who came up with the concept of limiting the American flag to 13 stripes, then adding stars for each new state.) In 1860, a man named Lincoln was nominated at the Republican convention in Chicago. By the time Cesnola and Reid tied the knot in June of 1861, storm clouds were gathering. The match was made to the chagrin of Mary’s friends and family, who believed she was marrying beneath her.

As war fever was everywhere and money was an issue, Mary came up with the idea of using Luigi’s vast military knowledge and experience and starting a school to train aspiring officers. With Cesnola’s pedigree and noble mien, the school quickly flourished and ended up training 700 officers for the Union war effort. Clearly, a man of his skills, talents, and political leanings toward freedom and human rights was destined to join the ranks of Lincoln’s army.

Cesnola was soon appointed colonel of the 4th New York Volunteer Cavalry and started recruiting at his and Mary’s expense. In the eyes of the young men he brought into the fold, he was a born soldier who would train and drill them even though many had yet to ride a horse!

In simplest terms, the Civil War was a battle of city boys versus country boys who grew up on horseback and were being led by beau sabres such as Jeb Stuart and Wade Hampton. Thus, in the early part of the war, the Union troops were outmatched and repeatedly defeated. Cesnola brought an aggressive and attacking approach to fighting. He also brought conflict upon himself with a slightly arrogant manner that brooked no slight to his honor. He was nevertheless doing well under Brig. General A. Duffié, himself a European emigre who had also seen service in the Crimea with the French cavalry.

Soon, Cesnola’s abilities were noticed. He was given command over five regiments (5,000 troops) under General Carl Schurz and was involved in numerous clashes in Virginia with units under the command of Lee’s brilliant cavalry commander Jeb Stuart. Through live action and constant drilling, Cesnola’s troops were becoming increasingly professional, no longer boys riding plow horses. Unfortunately, his career was sidelined for a few weeks after he was falsely accused, perhaps because of jealousy, in a matter of five pistols that were unaccounted for amid vast looting and war profiteering. The pistols were found.

The truth having won out, Cesnola was back as colonel of the 4th NY but was passed over for brigade commands in favor of his American-born counterparts, even though he had more experience and seniority in rank. As such, he was back in the saddle when his division fought the first engagement in which the Union cavalry claimed victory, sabre to sabre, against their albeit outnumbered Southern opponents at Kelly’s Ford in March 1863. Though a small action by Civil War standards, with only 3,000 men involved, it was important in that Jeb Stuart was present; the rebels were commanded by the well-regarded Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee; and, for the first time, a Virginia cavalry unit retreated in the face of a charge. A close reading of the battlefield maps produced by the American Battlefield Trust suggests it was Cesnola’s own 4th that made that successful charge.

Cesnola’s unit was then involved with General Stoneman’s first major Union cavalry raid. Taking place over four days behind enemy lines, it was designed to influence Lee’s movements before Chancellorsville. Given his recent success, Cesnola was placed in command of a brigade for what would be the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the Civil War, involving more than 20,000 men. It took place at Brandy Station, Virginia, in June 1863. The battle was a confused affair fought over nine square miles of rivers, hills, farmhouses and train tracks. Again, Cesnola was in the thick of things, even though his division was stationed at a corner of the battlefield. His brigade charged two Confederate cavalry regiments of about 600 men at Hansbrough’s Ridge, forcing them to fall back. Always leading from the front, he was said to have crossed sabers with several rebel officers in this engagement.

Cesnola’s next engagement would be his finest hour. The Battle of Aldie, about 40 miles west of Washington, D.C., was described as a “severe, savage fight between 4,000 men in 94-degree weather” in an American Battlefield Trust video. Aldie was important as a junction of two major turnpikes. The Confederate cavalry was moving north as a screen for Lee’s army, which was ultimately heading to Gettysburg. Lincoln was quite concerned as to the whereabouts of Lee’s troops and ordered his cavalry to learn what they could at all costs.

Unfortunately for Cesnola, Duffié had been demoted and replaced by divisional commander General Gregg. This reshuffling of officers resulted in a junior officer, some say a relative of Gregg’s, taking command of a brigade. Understandably angered by this perceived slight, Cesnola argued with General Gregg and, as a result, was placed under house arrest, with his sword and pistol taken away from him. His beloved 4th went into battle without him and was pushed back. Seeing his unit routed, he jumped on a horse and, with his unit’s acclamation, led them in a second charge that was successful.

Another general, witnessing this amazing feat, went over Gregg’s head and had Cesnola released from arrest just as another charge was called for. Seeing Cesnola had no weapon, the general offered him his own sword and said “bring it back with some rebel blood.” By a “gallant charge, [Cesnola] turned apparent defeat into a glorious victory for our arms,” according to a New York Times article. Unfortunately, the third charge (some say fifth) resulted in Cesnola not returning with his men. The colonel ended up “laying under his dead horse, a sabre cut three inches long on the crown of his head, a large cut in the palm of his hand and a gunshot wound in the upper part of his left arm,” Elizabeth McFadden wrote in “The Giitter and the Gold.” Cesnola was captured and sent to the Libby Prisoner of War Camp. In 1897, for his bravery during that battle, Cesnola received our nation’s highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, becoming the first Italian American to do so.

Libby Prison in Richmond was the second-most infamous prison in the Confederacy after Andersonville. It housed roughly 1,000 Union officers in cramped and unhealthy conditions. Fortunately, a fellow officer helped nurse Cesnola back to health. Numerous letters to his “dearest Mary” from her “Luigi” still exist. Besides requests for blankets and food, he asks for articles of women’s clothing, humorously telling her not to be jealous as he had no sweetheart. The items were clearly to be used as bribes for the mail censors to let her letters come through to him. Another amusing request was for flute sheet music from Verdi’s “Il Trovatore” to entertain the men. Cesnola was held captive from June 1863 to March 1864. His letters imply that other officers with more political connections were freed more rapidly.

After seeing his beloved Mary and his first-born daughter in New York, Cesnola was back in the fight in Virginia. His unit was part of General Sheridan’s cavalry, which was working with General Grant to defeat Lee. The 4th New York was in violent battles such as Cold Harbor and Trevilian Station, where Cesnola’s brigade was involved in seven assaults and repulsed with heavy losses. (There was another dashing young commander in the Union cavalry division at that time by the name of Custer). In private letters, Cesnola was critical of senior officers for the pointless loss of lives at Trevilian, the steady looting and burning of the homes of Southerners, and the mistreatment of women, which the cavaliere found horrible and attempted to prevent. His unit’s service was over in September 1864 after having fought in 47 battles of the great American struggle.

Following the war, Luigi and Mary were basically penniless. Fortunately, through friends in New York, Cesnola was able to secure the consulship of Cyprus. He became an American citizen in August 1865 and, somewhat controversially, began calling himself “general” in Cyprus to impress the Turkish authorities who controlled the island. There is much confusion over who was breveted a general during the Civil War, but this author believes Cesnola was only officially entitled to the rank of colonel. For the most part, he stopped referring to himself as count, which he occasionally did before becoming a U.S. citizen, though as a second son, he was entitled only to cavaliere.

The late 1800s were an era of amazing archaeological finds, such as the discovery that the city of Troy was an actual place, not just a story by Homer. It was in this atmosphere that Cesnola threw himself into scouring Cyprus for artifacts. Through several years of excavations and purchases, he was able to amass a significant collection. One of Cesnola’s goals was to prove that Cyprus was the link between Egypt and Greece in antiquity. Such were the significance of his finds that both the Russian and French governments considered purchasing them for their museums. Fortunately for him, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York wanted to flex its muscles versus its European counterparts. As the museum states on its website, “When the Metropolitan Museum opened at its current site in Central Park in 1880, the [Cesnola] collection was the focus of attention, heralded as a great asset to the city of New York, which was then aspiring to become a major cultural as well as business center. The richness and fame of the collection also did much to establish the Museum’s reputation as a major repository of classical antiquities and put it on a par with the foremost museums in Europe.” To substantiate his efforts, Cesnola published a tome on his work in Cyprus and the artifacts he uncovered. The archaeological field was nascent at this point, and there are criticisms that his excavations and those of other European explorers removed the cultural heritage of countries. Several men who clearly resented Cesnola’s success attempted to paint him and some of his findings as frauds but failed in the courts of both law and public opinion.

As part of his negotiations with the museum, Cesnola was named director, and in so doing, secured a place for himself and his wife in New York society. Mary became involved in “benevolent activities and helped to found an Italian Orphanage and the Christoforo Colombo Hospital in New York,” McFadden wrote. Luigi served tirelessly as the first director of the museum and was instrumental in the construction of its beautiful building along Central Park. “The Cesnola Collection remains a wonderful storehouse of ancient art and artifacts, and it is by far the most important and comprehensive collection of Cypriot material in the Western Hemisphere,” the museum website states. He worked at the museum until his death in 1904 and received praise for his dedication from the likes of J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilts. As someone with a significant amount of Italian blood, I enjoyed this line of the memorial resolution honoring Cesnola: “Somewhat restive in opposition and somewhat impetuous in speech and action but at all times devoted to his duty.”

The above appears in the August 2021 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

One comment

Pingback: Civil War hero Luigi Palma di Cesnola – Fra Noi - Fra Noi | Bible Prophecy In The Daily Headlines