An ammo bearer and then M-60 gunner for the Army, Paul LaFalce is still dealing with the psychic damage wrought during endless recon missions in the jungles of Vietnam.

One of four children, Paul LaFalce was born in Poughkeepsie, New York, to Anthony and Maria Scrivani LaFalce. He grew up there surrounded by his extended family. LaFalce’s paternal grandparents emigrated from Calabria and his maternal grandparents from Abruzzo.

LaFalce remembers many good cooks in his family. “Grandma LaFalce made the best meatballs and sauce,” he says. “And Grandma Scrivani made the best homemade cheese ravioli.” The LaFalce family, which included 11 children, was featured in a 1953 Life Magazine article about three generations of Italian immigrants in America. LaFalce’s father and eight brothers, all accomplished musicians, signed with RCA records and appeared on Arthur Godfrey’s show in 1954. “I was blessed to have grown up in our big Italian-American family in the 1950s and ’60s,” he says.

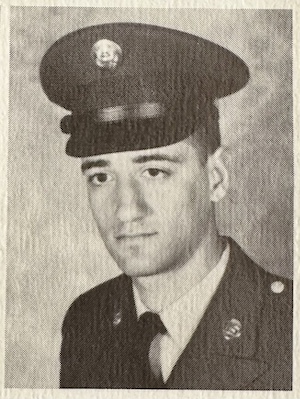

LaFalce attended Holy Trinity Catholic Grade School and Arlington High School. After graduating in 1967, he completed an airline training program and moved to Chicago to work with Eastern Airlines. LaFalce was drafted into the U.S. Army in March 1969. “I knew it was coming,” he says. “If you weren’t in college at 19, you’re going to get drafted.”

LaFalce completed basic and advanced infantry training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and received orders for Vietnam. After a brief leave in August 1969, he deployed and landed in Cam Ranh Bay. “I remember walking off the DC-8 and being shocked by the oppressive tropical heat and humidity,” LaFalce says.

LaFalce completed basic and advanced infantry training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, and received orders for Vietnam. After a brief leave in August 1969, he deployed and landed in Cam Ranh Bay. “I remember walking off the DC-8 and being shocked by the oppressive tropical heat and humidity,” LaFalce says.

Sappers, elite North Vietnamese soldiers, attacked camp that first night, bombing the hospital unit, killing eight bedridden American soldiers. “It was horrible!” LaFalce says. The soldiers took cover in above-ground bomb shelters outside the barracks. “We had no guns, nothing, no training,” he says. “We just got there and I’m just praying to God that somebody doesn’t come by and shoot us.” Air Force and Army helicopters bombed all around the camp’s perimeter. “It was a terrifying night for all of us new guys,” LaFalce says.

A few days later, LaFalce joined the Second Battalion, 35th Infantry Regiment, Fourth Infantry Division in Pleiku, in the Central Highlands. He was the ammo bearer for the M-60 machine gunner in the Reconnaissance Platoon. LaFalce later carried the M-60.

Recon conducted search-and-destroy missions in the dense, mountainous jungles. Huey helicopters picked the soldiers up at the forward firebase and dropped them in a landing zone in the jungle; the soldiers carried small arms, ammo, equipment and food, everything to survive for days on end as they conducted a combat assault. They “humped” along quietly looking for the enemy. “You can’t see,” LaFalce says, “maybe five, 10 feet away, it’s just vines, vegetation all over.”

LaFalce’s platoon patrolled in a column along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a supply route, keeping off the actual path to avoid getting ambushed. The point man broke a trail with his machete. “The vines would grab you,” LaFalce says. “Some days for a whole day we only made it 1,000 meters.”

The point man started shooting as he spotted the enemy and the soldiers dropped their rucksacks, carrying only their rifles and ammo and running to get on line. “Once all three squads got on line, all hell broke loose!” LaFalce says. “We opened up with everything we had: M16s, M60 machine guns and M79 grenade launchers.”

The platoon leader, radio operator and forward observer stayed behind calling in artillery and mortar fire support from the battalion firebase. Sometimes helicopter gunships and Air Force Phantoms provided fire support. “We knew how to fight. It was the only way to survive. Kill or be killed,” LaFalce says. “War is a horrible thing. I hated it then and hate it to this day.”

They camped out at night, in the thick of the jungle or just off a trail, setting up a perimeter and taking turns guarding. When the enemy was detected, all the soldiers were alerted. “We would blow off our claymore mines, start firing and wherever the enemy was we would get on line and chase him,” LaFalce says.

LaFalce fought in approximately 30 firefights out in the jungle, often staying out for 28 days at a time and coming in periodically to spend a night at the firebase. “It wasn’t like you’re just living in the rear, sleeping on a cot and all of a sudden you gotta go fight,” he says. “No, it was every day, up at daybreak and start humping.”

LaFalce was stationed in Vietnam for one year, nine months in the jungle and his last three months at the firebase manning a radar machine that detects motion. “I was very thankful at that point,” he says.

He shares two light-hearted memories:

LaFalce’s platoon had just returned to the firebase after 28 days fighting in the jungle. It was Christmas Eve 1969 and the men were looking forward to showers and hot food, but the colonel sent them back out to pull an ambush on the perimeter. “We were pissed!” LaFalce says. USO ditty bags, red with a cotton ball on the end, were dropped off to the soldiers on Christmas morning. LaFalce and his buddies made Santa beards with the shaving soap and placed the bags atop their heads. “We marched into the firebase shouting, ‘Ho, Ho, Ho! Merry Christmas!’ We woke everybody up,” he chuckles.

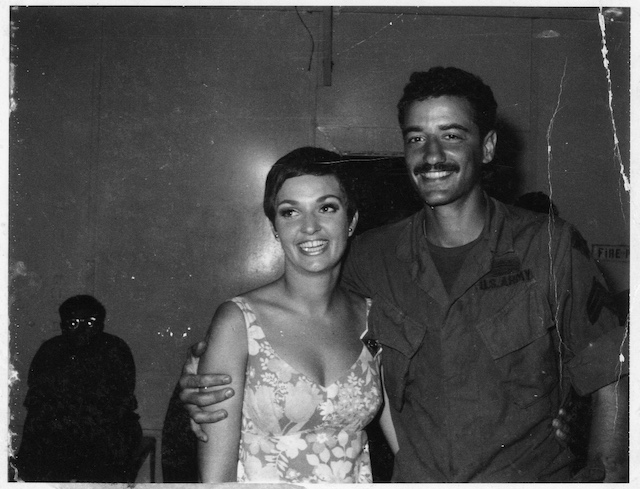

LaFalce flew into the Pleiku airbase for R & R the next day. “The Air Force fed me, gave me clean sheets and a blanket to sleep in a real bed, let me shower, shave and gave me clean fatigues,” he says. He heard about the USO show and pushed to the front of the line to meet Zelda of “Dobie Gillis” TV show fame and have his picture taken with Miss California. “What a treat that was!” he says.

LaFalce returned to the States in August 1970 as SP-4 and was stationed at Fort Carson, Colorado, until he was honorably discharged in March 1971. His most meaningful military award is the Combat Infantryman Badge. LaFalce returned to Chicago and Eastern Airlines while earning an associate’s degree in marketing from Triton College. Retired from a successful career in telecommunication sales, he and his wife, Darlene (Vanderslice), have three sons and five grandchildren.

LaFalce never talked about Vietnam when he returned. “We never knew if someone would say, ‘Thank you for your service,’ or ‘You’re a baby killer!’ ” he says. LaFalce was diagnosed with PTSD in 2004 and is grateful to the VA for treatment. The following year, he and his wife began attending annual reunions with his Recon buddies. “Thirty-five years of not speaking to my brothers in arms, we are reunited again,” he says. “This has been a remarkable healing process as we discuss our times together in combat.”

“Any war is horrible. I can’t believe how humans continue to do this to each other.” LaFalce reflects, “Thank God! He took care of me. I’m a lucky guy, I’m very lucky.”

The article above appears in the December 2024 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian