Originally trained by the Army as a typist, Patrick Mauro insisted on becoming a paratrooper and ended up guarding the border between West and East Germany during the Cold War.

The fourth of six children, Patrick Mauro was born and raised in Blue Island, Illinois, to Peter and Caroline Jones Mauro. He grew up in a town that was mostly German and Italian. Mauro’s paternal grandfather emigrated from Carovilli, Italy, to Ladd, Illinois, his father’s birthplace. Mauro’s extended family lived in the Taylor Street Italian enclave, and they visited each other regularly. He remembers sharing delicious homemade meals at family gatherings. “The ravioli always sticks out as a favorite,” Mauro says.

He attended Garfield Grade School and Thornton Township High School. In July 1961, a month after graduating from high school, a 17-year-old Mauro joined the Army. “My mom signed the papers,” he says. Two of Mauro’s uncles fought in World War II, and his father had worked in a plant that manufactured military materiel. As a young child, Mauro played war games with toy soldiers on the living room floor, his mother read him stories about the Civil War and he enjoyed watching war movies. “So it was always there,” Mauro says. “The military, the Army, especially, was always in the background.” His parents told him, “If you want to do it, it’s up to you. We’re not going to tell you what to do.”

Mauro arrived at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, in the heat and humidity of July, and they put him to work right away. “They had us picking up cigarette butts,” Mauro says. “I thought, God, what did I do?” He soon settled into basic training, his first time away from home. “I was bound and determined to do it, and I never complained to my parents once,” Mauro recalls.

He completed eight weeks of basic infantry training followed by eight weeks of advanced training as a typing clerk. Next, he traveled to Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, to become a personnel clerk. He finished the course in December 1961 and transferred to Fort Ord, California, where he was assigned as company clerk to a helicopter repair unit in Battalion Headquarters.

When Mauro enlisted, he informed the recruiter he wanted to be a paratrooper, but tests indicated he would do well as a clerk. Mauro was told he could always volunteer for the airborne. As company clerk, he heard that advisors and helicopters were going to Vietnam. “I thought I could volunteer for the airborne and maybe go to Vietnam, too,” Mauro says.

When Mauro enlisted, he informed the recruiter he wanted to be a paratrooper, but tests indicated he would do well as a clerk. Mauro was told he could always volunteer for the airborne. As company clerk, he heard that advisors and helicopters were going to Vietnam. “I thought I could volunteer for the airborne and maybe go to Vietnam, too,” Mauro says.

He hand-delivered his application to the post commander’s office on base. All communications from the Department of the Army in Washington were done by teletype machines. One day, he saw his own orders come through for a transfer. “All your life, you remember vivid things; this sticks in my memory,” Mauro says. “It was unbelievable.”

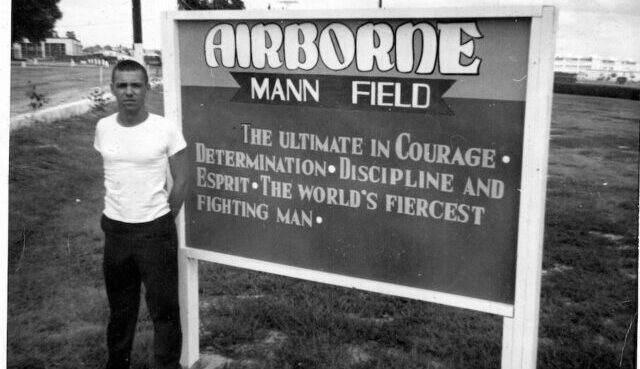

Mauro was granted two weeks leave before reporting to Airborne School in August. “In July, 10 days after I left to go back to Blue Island on leave, the unit I was in went to Vietnam,” he says. Staying behind, Mauro completed Airborne School and flew to Mannheim, Germany, where he was stationed at Coleman Barracks in Battalion Headquarters, once again as a clerk. Mauro told his company commander, “I want to be in an airborne troop. I don’t want to be in headquarters filing papers and filling out forms and all that.” A couple of months later, he transferred as a paratrooper to the Airborne Troop, 3rd Reconnaissance Squadron, 8th Cavalry, 1st Airborne Brigade, 8th Infantry Division.

Mauro arrived in Mannheim in October 1962, at the height of the Cold War, and remained there until July 1964. Two pivotal events that occurred in the years before he arrived were the Cuban Missile Crisis and the building of the Berlin Wall. “So that was in the background constantly,” Mauro says. He was part of the NATO deployment, a check against any perceived Soviet threats.

Part of an airborne scout outfit, Mauro was either on the ground or airborne, and maneuvers were done with either armored or airborne equipment. “Every two months, I was jumping for training in the airborne in Germany,” says Mauro.

The border between West Germany and East Germany was called the Fulda Gap, guarded day and night by troops rotating in 12-hour shifts. Mauro would travel from Mannheim to the Fulda Gap base camp with his unit of 150 soldiers. From there, three or four of them, carrying radios and M14s, would ride to the border in an armored personnel carrier. “We were overlooking the border, the towers, the barbed wires,” Mauro says. “It was heavily fortified.” One man was positioned in the bunker, about 100 yards away from the border, sometimes in frigid temperatures. “Nobody wanted to be in the bunker. It was five below, and you’re thinking to yourself, ‘How did I get into this?’” Mauro says.

Rumbling through rural towns with tanks and armored vehicles, Mauro saw farmers hard at work. “It was shockingly old school. You didn’t see a lot of farm equipment. You saw a lot of manual labor,” he says. “People just looked like they were downtrodden.” Mauro continues, “The atmosphere because of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, that atmosphere made you realize that you’re in the boondocks.”

Seventeen years after World War II, heavily damaged buildings and destruction from artillery and heavy guns were still evident. “You had to feel like [the war] was yesterday,” Mauro says. “You would see helmets, shells, remnants of weapons. It wasn’t everywhere, but you’d find them when you were out in the boondocks.”

At Checkpoint Charlie in West Berlin, everything was repaired and modern. Mauro looked into East Berlin and saw rubble and bombed-out buildings. “It was heavily damaged,” he says. “It was an education.”

On a perfectly starlit night, dressed in full combat gear including his M-14 rifle, Mauro took the final jump of his Army career, his only night jump. “Exiting the plane, I felt like I was in a bowl surrounded by moving stars,” he says. “Of course, the stars were not moving. I was just tumbling as usual from the prop blast and the ‘long’ few seconds it takes for the parachute to fully deploy. For me, that was really exciting and memorable.”

Mauro completed his tour in Germany and boarded a troop ship to New York on July 2, 1964. During the eight-day trip, he was responsible for guarding prisoners headed to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Sgt. E5 Mauro was discharged on July 10 and returned to Blue Island. He earned a bachelor of science in finance from the University of Illinois and enjoys a successful career as an investment adviser. Mauro and his wife, Mary Ellen Haney, have two children and two grandchildren.

Reflecting on his time in the Army, he says, “You grew up! When you’re 17, you’re just a kid. You’re a teeny bopper, and it stopped immediately.” While stationed in Germany, he never experienced any hostility from the civilians, noting that, “Basically, the Germans knew that we were the bulwark against the Soviet Union.”

The above appears in the May 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian