Barely out of high school, Vincent Speranza fought nonstop across Europe from the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 until the Nazis surrendered in May 1945.

One of eight children, Vincent Speranza was born in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan in 1925 to Francesco and Francesca Paratori Speranza. Francesco immigrated from Palmi, Calabria, and Francesca from Sciacca, Sicily. When Speranza was 3 years old, they moved to Staten Island, where he grew up amid a large extended family.

Every Sunday at noon, the family took turns hosting a traditional spaghetti dinner with all the trimmings. “A real Italian spaghetti dinner on Sunday was two-and-a-half, three hours,” Speranza says. He graduated from PS 22 Grade School and Port Richmond High School. Speranza remembers his family gathered around the radio, listening as President Roosevelt declared war on Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack. “My father was a tough guy, and it was the first time we saw tears in his eyes,” says Speranza. He lined up his four sons, ages 12-20 and said, “Boys, listen, this country must not fail because nowhere in the entire world can a man come here with nothing except the willingness to work and look at us today. We have a home. We have a car.” Speranza never forgot those words. “From that day on, everything or anything I’ve done is doing my little share to make sure this country does not fail,” he says.

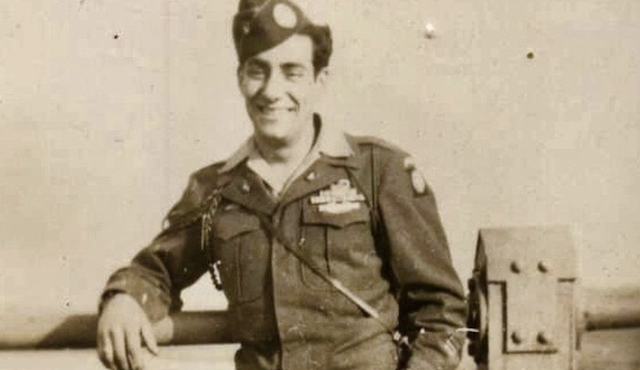

Speranza was drafted into the Army in October 1943 and completed basic and advance infantry training at Fort Benning, Georgia. “From 18-year-old innocent kids in high school, we were something else when they got through with us,” Speranza says. He was assigned to the 87th Infantry Division and trained at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, with maneuvers in Tennessee and Florida. Speranza volunteered for the Parachute Infantry and trained at Fort Benning, assigned to H Company, Third Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. “The confidence they gave us when we left there to go overseas, we were ready to take over the German army by ourselves,” Speranza says.

In November 1944, he deployed to England on the Queen Mary. “We were itching to get into the war,” says Speranza. His outfit flew to Camp Mourmelon in Northern France as replacements in the 101st Airborne Division. “When you’re a replacement, you are nothing,” Speranza says. “Until you prove yourself in combat, nobody talks to you.”

It was mid-December, Hitler was making a push to take Bastogne, a transportation hub, and Eisenhower called out to all Airborne Divisions. “My first jump was off the back of a truck,” Speranza says. “All my airborne training!”

They arrived one day before the Germans. “Just enough time to dig in and make a defense line, which was so effective for the entire eight days of the battle for Bastogne, not one Nazi boot ventured past town,” Speranza says. He was a machine gunner in a forward foxhole outside of town. The soldiers had no winter clothing, and food and ammunition were in short supply, but that did not deter them. The attitude was, “I don’t care what you guys throw at me, you’re not getting by my foxhole!” says Speranza.

The Germans were pushed back the first day. The second day, they surrounded Bastogne, bombing, strafing and shelling day and night, flattening the town. The field hospital, medical equipment and personnel were wiped out, leaving only one doctor and nurse. The doctor operated by candlelight, with no morphine, in makeshift quarters in the church, the only building with walls that were still standing. On a town run, Speranza checked on his foxhole buddy, wounded in both legs, who asked him for something to drink. “Well, hey, when your foxhole buddy wants a drink, you go find a drink,” says Speranza.

He found a working beer spigot in a bombed-out tavern. Looking around for a container and finding none, Speranza removed his field helmet, filled it and hurried back to his buddy. Of course, everyone else wanted beer, too. On his second trip, he was stopped by the medical officer, who asked, “What the hell do you think you’re doing, soldier?” to which Speranza replied, “Bringing aid and comfort to the wounded.”

Bombing continued all around the perimeter. “You jump up and do the best you can with the little ammo you had,” Speranza says. “But we beat off every attack.” Patton pushed through on Dec. 26 with reinforcements. “We broke out of Bastogne and started cleaning up the area all around there where the Germans were.” The troops began pushing Nazi forces back to Berlin.

On Jan. 6, Speranza was wounded under his eye. After recuperating in a British hospital, he rejoined the 101st as it moved toward Czechoslovakia and Austria, then Bavaria, fighting all the way. “I was always in the combat zone all the way to the end of the war,” Speranza says. His outfit served as regular ground troops, pushing the Germans out of towns.

Searching through a forest, the soldiers smelled a stench that became stronger and stronger. At the clearing stood a concentration camp. “The sight there shocked us all,” Speranza says. Bodies were piled high next to a huge hole. Prisoners crawled on their elbows toward the soldiers, kissing their boots, hugging their feet. “Don’t forget we were 19-year-old kids. You see all that, you were sick at your stomach, you were angry, you were sad,” says Speranza. “I don’t believe what I’m seeing. I don’t believe it!”

The war ended in Europe, and Speranza was preparing to invade Japan when the atomic bomb was dropped. Private Speranza was discharged in January 1946. Among his many medals are a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star and the French Legion of Honor. He returned to Staten Island and received a bachelor’s degree from Wagner College and a master’s degree from New York University. He then taught American history in New York City high schools.

Speranza married Iva Leftwich in 1948. “She turned me into a gentleman schoolteacher from a badass paratrooper,” he says. A widower, Speranza has two surviving children, nine grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Speranza is the author of “Nuts! A 101st Airborne Division Machine Gunner at Bastogne,” a book about fighting at the Battle of the Bulge.

Sixty-five years after the war, Speranza returned to Bastogne to commemorate the anniversary of the battle. While sharing lunch with two European tank officers, he told them the story of his World War II beer run. Hearing the tale, they ordered the tavern’s “Airborne Beer.” The waiter brought a bottle featuring a U.S. soldier carrying a helmet full of beer, along with a ceramic helmet from which to drink it. Up until then, everyone thought the story was only a legend. No one was more surprised than Speranza.

Reflecting on his service during the war, Speranza says, “Ten minutes after you’re in combat, you’re a changed man. Your attitude was, ‘Some of us are going to make it; some of us aren’t.’ But, meanwhile, do your job and do it right, and you might save more of your guys.”

The above appears in the February 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian