Rejected for medical reasons and later trained as a medical corpsman, Ralph Pasqurella had his hands full during the invasion of Normandy and throughout the European campaigns in World War II.

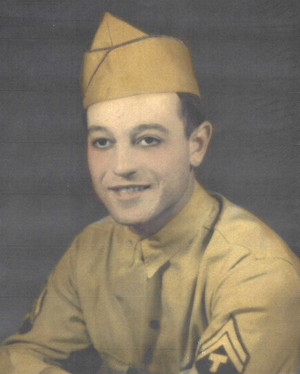

Ralph “Hack” Pasqurella was born in Melrose Park in 1917 to Gaetano and Gabriella Chiero Pasqurella, who immigrated to the U.S. as teens. His father came from Melizzano in Campania and his mother from Trivigno in Basilicata. Pasqurella’s father died during the 1918 flu epidemic while his mother was pregnant with their second child. She eventually remarried and had six more children.

Pasqurella’s maternal grandmother lived with the family and he remembered her as a hard worker, whether she was gardening in the backyard or cooking. He especially loved her macaroni. The family belonged to Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish and relatives always gathered together for the Feast Day in July. His grandmother cooked and cooked, he said, and the celebration was almost bigger than Christmas.

Pasqurella graduated from Stevenson Grade School and attended Proviso High School for two years before dropping out to work for the Civilian Conservation Corps to help his family during the Depression.

A government-run program, the CCC hired young men for environmental and infrastructure projects. Pasqurella’s first assignment was in Idaho for three months. It was his first time away from home. “I was kind of homesick; then I got over it.” He worked trimming trees in parks. “I liked it. I was a little kid, but I made it,” Pasqurella said. “We got 30 dollars a month: 25 went home and 5 you got for yourself.”

Next, he went to California for six months. “We built a road up in the mountains,” Pasqurella said. Then he returned home and worked at Richardson Company in Melrose Park. Pasqurella remembered playing football with the Melrose Park Gaels on December 7, 1941, when Pearl Harbor was attacked. “We heard it from the fans,” he said. “It was sad!” He attempted to join the Army but was declared 4-F because of a perforated eardrum. The Navy turned him down due to color blindness.

Pasqurella continued working, married Corrine “Rena” Giacamozzi, and was drafted into the Army in October 1942. Suddenly the 4-F status was no longer significant. Rena was pregnant and did not want him to leave. “She didn’t like it,” Pasqurella said. “She started to cry.” He was inducted at Camp Grant in Rockford, where he recalls being told, “You’d make a good gunner on a B-24 or B-17 but we ain’t gonna send you there. We’re gonna send you to the Medical Corps.”

Pasqurella trained for three months at an infirmary in Idaho. He then transferred to California and worked in a dispensary for six months. While he was there, Pasqurella’s wife went into labor and she and their child both died during childbirth. He had a brief leave, completed his training and deployed overseas as a medic, assigned to the Second Infantry Division, 462nd Anti-aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion.

Pasqurella trained for three months at an infirmary in Idaho. He then transferred to California and worked in a dispensary for six months. While he was there, Pasqurella’s wife went into labor and she and their child both died during childbirth. He had a brief leave, completed his training and deployed overseas as a medic, assigned to the Second Infantry Division, 462nd Anti-aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion.

After a couple of months in Scotland, Pasqurella headed to England. On the morning of June 6, he crossed the English Channel aboard a landing craft as part of the second wave of the D-Day invasion. German troops defended the beach from their fortifications as Pasqurella came ashore. “They threw everything at us but the kitchen sink!” he said.

Destroyed vehicles littered the water’s edge. Bodies lay on the beach and wounded soldiers cried for help as others scrambled for protection. “All I remember is hearing ‘Medic! Medic! Medic!’” Pasqurella said. “Two, three wounded guys at one time.”

Medics wore big red crosses on their chest, back and arms and the Germans were not supposed to shoot at them. Pasqurella tended to the wounded the best he could as bullets whizzed by him. “The first thing was control the hemorrhage if they were really bleeding,” he said. Pasqurella administered aid and stabilized soldiers with shrapnel wounds, internal bleeding, and broken and missing limbs. “We had litter-bearers,” he said. “I did the first aid and they carried the wounded back (to the first aid station).”

After establishing a beachhead, the soldiers moved inland, advancing to the battle at St. Lo. “Oh man, that was rough!” Pasqurella said. “The whole town was leveled. The only thing that was standing was the church steeple.”

Pasqurella and his battalion pushed on, taking part in the liberation of Paris. “Oh, that was something else,” he said. Soldiers slept in foxholes or wherever they could. “We medic guys slept under the Eiffel Tower,” he said. Pasqurella attended Sunday morning Mass at Notre Dame Cathedral. “Oh, that was huge,” he said. “Beautiful.”

From Paris, the Second Infantry advanced through to Belgium in December 1944 to fight the Battle of the Bulge. Leaving out the gruesome details, Pasqurella once again said “That was rough!” to describe the battle. Fighting was hard in the cold, snowy forest as the Germans brought in more troops. “They proceeded to give us a beautiful present,” Pasqurella said. “Big shells coming in!”

Battered but victorious, the Allied forces continued their thrust across Europe. By March or April of 1945, Pasqurella was in Regensburg, Germany, once again under enemy fire. “We were getting shelled and I jumped into a foxhole and who jumped into the foxhole right after me was a boy from Melrose Park,” said Pasqurella. “Honest to God! Isn’t that something?”

Pasqurella grew up with Gus Sperando, one of six brothers, and the two caddied together in Northlake. Surprised to find one another under such circumstances, the friends talked briefly while sheltering in the foxhole.

When the European war ended on May 8, 1945, Pasqurella’s unit was in Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, where they met up with Russian soldiers. “All they wanted was chocolate and cigarettes from the U.S. soldiers,” he said. “Chocolate! Chocolate! Cigarette! Cigarette!” Pasqurella and his buddies celebrated with vodka and cognac they acquired in trade from the Russians.

Pasqurella took part in five major European campaigns: Normandy, Northern France, Ardennes, Rhineland and Central Europe. “The five campaigns were a rough part of my life,” he said. During each battle, he tended to the wounded the best he could, stabilizing them before sending them to the field hospital.

He arrived in New York in August 1945. After undergoing hernia surgery, he was discharged as Technician Fourth Grade on Dec. 19, 1945, and returned home to Melrose Park. “Oh, my God, everybody was crying, especially my mother,” Pasqurella said.

Pasqurella married Cecelia Macro in 1946 and they had one daughter. He retired from the River Forest Street Department. Among his numerous awards is the Silver Star.

Ralph “Hack” Pasqurella passed away on July 13, 2010. The quotes and other information in this article come from an interview conducted and archived by the Melrose Park Library’s Veterans History Project and are used with the library’s permission. (mpplibrary.org/vhp)

The above appears in the February 2024 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian