Mere months before full-scale battles raged across Vietnam, Paul Calabrese engaged in deadly skirmishes in the jungles around his base camps to ward off enemy incursion.

The oldest of four sons, Paul Calabrese was born in Chicago to Joseph and Betty (Spindler) Calabrese. They lived in a family-owned six-flat on the West Side of Chicago until moving to Oak Park when Calabrese was 6 years old.

The oldest of four sons, Paul Calabrese was born in Chicago to Joseph and Betty (Spindler) Calabrese. They lived in a family-owned six-flat on the West Side of Chicago until moving to Oak Park when Calabrese was 6 years old.

He recalls Sunday dinners and Christmas gatherings at his paternal grandparents’ home. “I remember grandma making raviolis all the time and they lived in the basement,” says Calabrese. He explains that his grandparents had a beautiful home, but family always gathered downstairs. “I never saw the upstairs furniture,” he says. “It was always covered with sheets.”

Calabrese attended Lincoln Grade School and graduated from Oak Park-River Forest High School in 1964. He attended University of Illinois for one year and, unsure of his career path, decided to work instead. Calabrese was employed at a machine shop in Cicero when he was drafted into the Marines in March 1966.

Both parents served in the Army during World War II, his mother as a secretary at the Pentagon and his father in the motor pool. They met at a USO dance in Philadelphia. “They didn’t want to see me in the service, but then again they were both service oriented,” Calabrese says. “They saw the obligation as well as I did.”

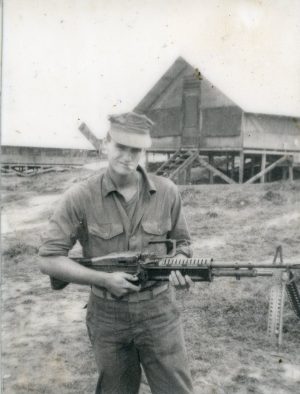

He completed boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego and infantry training at Camp Pendleton and specialized as a machine gunner. After a brief leave, he was sent overseas to Vietnam. “At the time I felt it was inevitable, the war was starting to escalate and there was a certain naiveté on my part,” says Calabrese.

Assigned to the Weapons Platoon, Echo Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, Calabrese spent the first three months of his tour at a base in Chu Lai. The area around the base had been secured during previous combat and Calabrese’s platoon patrolled daily and set up ambushes to protect it. “If there was any engagement, the Viet Cong would augment the engagement most of the time,” Calabrese says. “It was their country; it wasn’t ours.”

His unit moved on to the town of An Hoa in the Quang Nam province about 25 miles west of Da Nang. “Chu Lai had a big military airbase and the same thing with Da Nang, another big military airbase and early on we were just there to establish perimeters around the base,” says Calabrese.

He was not engaged in heavy battle, but was constantly on patrol with his platoon, always alert to snipers and land mines. “I was doing my job of sorts … you’re young, 19, 20 years old.” Calabrese says. “You’re invincible.” He recalls an old saying, “Give a soldier testosterone and a cause and that’s all that’s required.”

Calabrese witnessed soldiers maimed and killed after setting off a land mine or tripping a booby trap. “I saw a sniper take a shot at the medic that was running to take care of a guy that got shot,” says Calabrese. “So it was more like a cat-and-mouse type of thing. It wasn’t like the big battles later on.”

A road built between Da Nang and An Hoa was called “Liberty Highway.” When at the base camp, Calabrese patrolled that road daily to ensure safe passage for convoys between the two points. Minesweepers checked for land mines.

At times Calabrese and his platoon were off the main base for three or four weeks establishing perimeters in a 30-40 square mile area in the foothills of the mountain range. “One week we would be around a battalion rear area, once again patrolling there and in the villages to make sure everything was okay,” Calabrese says. He explains that all the aggressions were on the part of the enemy. “If they felt they could engage us, they would,” he says. “Otherwise our ambushes very seldom were successful. They knew where we were more than we knew where they were.”

Calabrese was in charge of a machinegun team during a patrol when the North Vietnamese Army hit with an L-shaped ambush. He and his team were on opposite sides of the road. “They got killed and I didn’t. It just happens in a minute, like a blur,” he says. “I didn’t get scratched!”

Calabrese was in charge of a machinegun team during a patrol when the North Vietnamese Army hit with an L-shaped ambush. He and his team were on opposite sides of the road. “They got killed and I didn’t. It just happens in a minute, like a blur,” he says. “I didn’t get scratched!”

His good buddy Joe was among those killed in that attack and when asked if he wanted to say goodbye to him, Calabrese said no. “I did not want to see my friend when he was killed,” he says, “It’s not like going to a funeral home.”

In a nighttime patrol, Calabrese and his platoon boarded rafts to cross a river into an unknown area and began their patrol. The soldiers were going up a hill when mortar rounds flew in. Calabrese was hit in his right forearm. He was immediately medevaced to Da Nang for preliminary surgery, stabilized and transported to Clark AF Base in the Philippines and then assigned to an AF Base in Okinawa. The shrapnel severed a tendon, which was reattached, the muscles were stretched and Calabrese underwent therapy to his arm. “It was really kind of ideal, clean sheets every night and I had three squares,” he chuckles. “It was like heaven.”

After six weeks in Okinawa, Calabrese was fit to return to his outfit. “My mother didn’t think that was the right idea,” he says. “She thought, ‘Oh okay, you got wounded over there, that’s it. You did your time over there, go home.’”

During his time in Vietnam, Calabrese corresponded regularly with his parents and received care packages. His mother sent Kool-Aid, candy and cookies, and his father sent a bottle of Jack Daniels every month!

Cpl. Calabrese’s Vietnam tour ended in November 1967 and he was stationed at Camp Pendleton until discharged in March 1968, receiving the Purple Heart for his injuries. Calabrese returned home to Oak Park and then attended Western Illinois University on the GI bill, graduating with a degree in fine arts and working in the printing industry for many years. Calabrese and his wife Linda currently own a successful catering company in River Grove. They have a family of four children and five grandchildren, and he is active in the VFW and the American Legion in River Grove.

Reflecting on his time in Vietnam, Calabrese says, “To be honest with you, the whole experience of the service in Vietnam is you are isolated. You went overseas by yourself. You join a group there and when your time is up, you just left. The group might still be there, but you came back by yourself.” He concludes, “It changed me forever and it gave me an opportunity to go to college.”

The above appears in the March 2020 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian