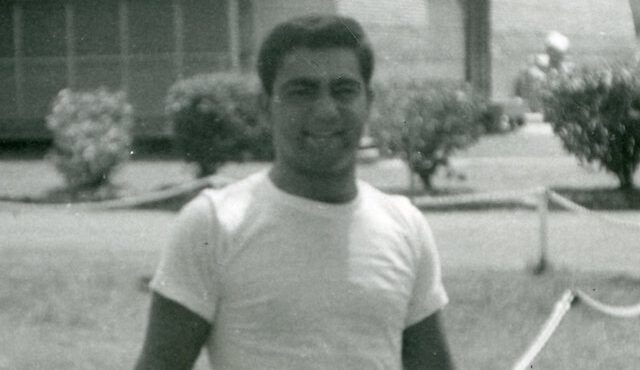

As a Navy Seabee, Anthony Pucillo helped create housing and infrastructure for installations throughout the Pacific after the Korean War.

The oldest of three sons, Anthony Pucillo was born in Chicago to Ernest and Theresa (FioRito) Pucillo. The family lived in the Jane Adams Projects on Taylor Street until Pucillo was 5 years old. “We moved around quite a bit,” he says. Both parents were born in Chicago, and his grandparents emigrated from Sicily and Calabria.

A “very good cook,” Pucillo’s mother made traditional Italian dishes in addition to fried chicken and breaded veal steak, two meals he especially liked. “My father had to have his pasta every Sunday, and he had to eat by 1 o’clock,” Pucillo says. Christmas Eve was spent with the Pucillo side of the family, and his grandmother and aunts made more than 100 ravioli by hand. “There was no machine then,” he says. “That was our favorite.” Christmas Day was celebrated with the FioRito family, sharing their special dishes. “My aunts baked a lot,” Pucillo says. He loved their scalille, a traditional Calabrese cookie dipped in honey.

Pucillo attended Tobin Grade School and Reavis High School. After graduating, he enrolled in Washburne Trade School, attending classes one day a week to learn cement finishing while working as an apprentice at construction sites. Pucillo’s grandfather, father and four uncles were all in the Cement Masons Union, but after a year or so, he was unsure of his future. At the time, many of Pucillo’s friends were joining the military. “I figured, well, let me serve my country,” he says. He enlisted in the Navy in 1955. “I wanted to be on a ship and see the world,” Pucillo says.

He attended Boot Camp at Great Lakes and after graduating, met with a counselor for placement. Pucillo mentioned he was an apprentice cement finisher and showed the counselor his union card. “So he opened up a book and started asking me questions out of it, and I gave him the answer before he could finish the question,” says Pucillo. “After eight questions, he closed the book and said, ‘You’re going to go to the Seabees.’”

The United States Navy Construction Battalions, better known as the Seabees, were special units equivalent to the Army Corps of Engineers. Sailors normally trained for six months at Port Hueneme, California, before being assigned. “But because I already had a year and a half of experience, they sent me right over to Guam,” Pucillo says. He flew from Chicago, stopping at an Air Force Base in California and Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii before arriving at his destination.

“Here I was 18 years old, never been away from home, flying overseas on Christmas Eve,” says Pucillo. Thoughts of his family flooded his mind: gathering at his grandparents’, attending Midnight Mass together. “I felt lonely, very lonely,” Pucillo says.

Once on the island, he quickly settled into a daily routine, living in a Quonset hut on the Seabee base. The hut held sleeping accommodations for 20 sailors. “Everyone had a fan at the end of their bunk to keep the mosquitoes off,” Pucillo recalls.

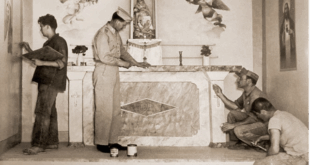

The Seabees included electricians, plumbers, cement finishers, engineers, carpenters and all other sorts of construction workers. “Everybody did their own thing,” Pucillo explains. “I happened to go to the concrete group because I was a cement finisher.” He was in MCB (Mobile Construction Battalion) 10. After breakfast, the 12-14-man crew climbed aboard a truck that drove them to the construction site, where they built houses for Navy personnel and their dependents. “We were building three-story complexes,” Pucillo says.

The first load of concrete was delivered to the work site in the early morning, and the crew got busy. Another load arrived at around noon. “We’d pour maybe two to three slabs a day, and then we’d stay there to finish it,” Pucillo says. Often working 10-hour days, they would complete their shifts only after the cement set. “When you finished, you finished,” he says. “Very seldom would we get done within an eight-hour day.” Boxed lunches were delivered to the construction site, and the mess hall stayed open late so Pucillo and his crew could eat dinner.

With evenings and weekends off, the sailors frequented a bar on base when they were off duty and traveled to another base to see movies. The small village of Agat housed a movie theater and taverns but no restaurants. “I think they had one pizza place on the island,” Pucillo says. “We’d throw picnics on the beach for ourselves.”

Every so often, Pucillo traveled to Midway, Wake and Johnson, small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. “They would fly us there, and we would build airstrips,” he says. “We would go in there for any kind of construction they needed and then go back to Guam.”

After his 18-month tour of duty, Pucillo flew to Pearl Harbor to remodel Camp Smith, a Marine air base where he worked on both a paint crew and a bricklaying crew. “I was a soldier. I did what they told me to do,” he says. “Wherever they needed me, that’s where I went.”

Third Class Petty Officer Pucillo was discharged from Pearl Harbor in 1958, after serving three years in the Navy. “Any time I traveled, I was never on a ship. I was always flown by air,” chuckles Pucillo. “Three years and never on a ship. They tell me I was very lucky. That was a special unit.”

He returned to Chicago and, because his time with the Navy Seabees counted toward his apprenticeship, was issued the full journeymen card. Only 21 years old, he became the cement finisher foreman on the Calumet Skyway. From there, he went to work on the Dan Ryan Expressway. After 10 years with private contractors, Pucillo began working for the City of Chicago. During his 33-year career with the city, he rose from cement finisher foreman to first deputy commissioner of the Chicago Department of Transportation.

Pucillo retired in 1998 and entered the private sector, first as a partner in M & Q Construction, then as a consultant. He has four children and eight grandchildren. Through the years, Pucillo has been active in numerous fundraising events for charitable causes, among them the Children at the Crossroads Foundation, which provides need-based scholarships. In recognition of those efforts, he will be honored as a 2021 Humanitarian of the Year by the Italian American Executives of Transportation in November.

The camaraderie in the Seabees led to many lasting friendships, according to Pucillo. Reflecting on his time in the Navy, he says, “It helped me widen my scope. You learn how to respect authority. That’s a lesson that doesn’t cost you $60,000 a year in tuition.”

The above appears in the May 2021 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian