A bus driver with his father’s sightseeing company before World War II, Donald Ferrone played a key role in a unit charged with transferring materiel from England to Germany after the war.

Donald Ferrone was born in Oak Park, Illinois, to Henry and Filomena Trimarco Ferrone, who were from the Little Italy on Taylor Street. He had one younger brother, Francis. Ferrone’s paternal grandparents emigrated from Salerno, Italy, and his maternal grandparents from Naples. The family lived in West Chicago before moving to Oak Park, across the street from Ferrone’s maternal grandparents. Ferrone proudly notes that his grandfather, Anthony Trimarco, immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 14, worked for the city of Chicago and was later elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1910 and 1912.

Ferrone grew up within a very large family: His father was one of six children, and his mother was the oldest of 14. “It was a ritual on Sunday that every afternoon there’d be about 15-18 of us having dinner at Grandma’s house, and around 5 or 5:30, we’d all gather and listen to Jack Benny (on the radio),” he says.

Ferrone graduated from St. Catherine Siena Grade School and was attending St. Phillip High School when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Suddenly, four of his uncles living across the street were fighting for their country. “We wondered what was going to happen,” Ferrone remembers.

Influenced by his uncles and father, who fought in World War I, Ferrone joined the United States Army Air Force Reserves in high school, hoping to become a pilot. His father was drafted into the Army in 1917, was attached to the highly acclaimed 42nd Rainbow Division and fought in the horrific Champagne Battle in France from July 14-15, 1918, a turning point in the war. Thousands of soldiers were killed, and Henry was one of thousands more wounded. The soup bowl-shaped helmet he wore saved his life when a bullet hit the metal and bounced off the thick rubber binding. “Otherwise, the bullet would have gone into his head,” Ferrone says. His father never talked about the war or about being wounded. When Ferrone was around 10 years old, an uncle told him what had happened. The family attended annual reunions of the Rainbow Division, and the men never mentioned the war. “They used to talk about all these funny things,” Ferrone says.

Ferrone graduated from St. Phillip in 1944 and attended Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, to become a pilot. There was a surplus of pilots, however, so he was transferred to Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas. Ten days into training, Ferrone and about 35 men contracted spinal meningitis, fell seriously ill and were quarantined for more than a month. He doesn’t remember much about that terrible time. “All I know is I was kind of paralyzed for a while,” Ferrone says. “I couldn’t move my legs.”

Ferrone graduated from St. Phillip in 1944 and attended Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, to become a pilot. There was a surplus of pilots, however, so he was transferred to Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas. Ten days into training, Ferrone and about 35 men contracted spinal meningitis, fell seriously ill and were quarantined for more than a month. He doesn’t remember much about that terrible time. “All I know is I was kind of paralyzed for a while,” Ferrone says. “I couldn’t move my legs.”

According to Ferrone, his parents were told that if they wanted to see their son alive, they had to get there fast, so they came. “But they could only see me through glass because of the quarantine.” Deathly ill, Ferrone was anointed with last rites and remembers the priest. “He was a major, and his name was Major,” Ferrone says.

Half of the sick men died, but Ferrone recovered and transferred to Keesler Field, Mississippi, for ground crew training with mechanicals. “I was just happy I was able to move around and get out of the hospital,” Ferrone says. He completed the two-month course and returned to Texas for additional training at Randolph Field. He does not know where his previous unit was deployed.

In January 1946, he boarded a Liberty Ship in New Jersey for a rough nine-day crossing. “We hit a storm,” Ferrone says. “I thought that Liberty Ship was going to break in half.” They landed in Le Havre, boarded a troop train to Paris, then went on to Munich. Ferrone spent several days at a closed Luftwaffe base in the forest before heading to Royal Air Force Burtonwood in Warrington, England. The base was 99% closed by the time Ferrone arrived.

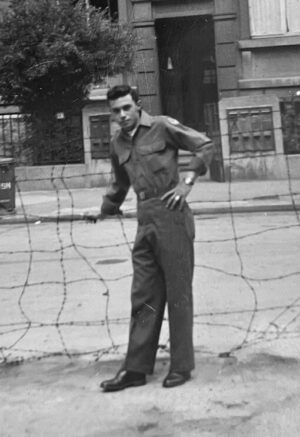

Pfc. Ferrone and the others in his unit were responsible for removing items left from the war. “We were told we got to move all this equipment that’s left over and get it to Liverpool, and then it’s getting on ships going to Army bases in Germany,” Ferrone says. The leftover equipment included airplane engines, miscellaneous engine parts, tanks, trucks, planes and parachutes. The lieutenant pointed to the parachutes and said, “Fellows, any of you getting married soon? If you are, take one of the parachutes, put it in your duffel bag and bring it home. It will make a good wedding dress.”

They loaded everything onto heavy-duty double-clutch Army trucks, but only a few men knew how to drive them. Because Ferrone had experience driving buses at his father’s company, he was put in charge of training the others and became the designated lead driver. “They’d load up the trucks, and we’d drive them to Liverpool, and they’d unload and put them on ships, and we’d come back and get another load,” Ferrone says.

His next assignment was at Wiesbaden Air Base in Germany. Ferrone was attached to the 47th Liaison Squadron, with approximately 12 L-5s, small planes used by the Army Air Force as their standard liaison aircraft. They were primarily used for short-range officer transport, courier work and artillery spotting, but also as an air ambulance or light cargo transport. As part of the ground maintenance crew, Ferrone repaired the planes as needed.

He then transferred to the Frankfort Air Base, attached to the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. At the time, the Nuremberg Trials were ongoing. “Every once in a while, we’d get a call that they were going to bring papers over, and we’d fly them to the Nuremberg Trials,” Ferrone says.

Much of Frankfort was destroyed during the war. Many buildings lay in ruins, and others were partially standing. “Every morning when we’d go down the streets, people would be coming out of the buildings,” Ferrone says. “That’s where they lived.” The Army hired the displaced persons to cook, clean, sew, etc. “The only ones that had a real comfortable life were the ones that were authorized by the Army to work for them,” says Ferrone. Payment would be made in candy bars, cigarettes, soap or whatever they might ask for. “These items were then traded for food, milk or clothing for their families,” Ferrone says.

Cpl. Ferrone returned to Chicago in November 1946, was discharged and drove for his father’s business, the Chicago Sightseeing Company, eventually retiring as CEO and president. He and his wife, Kay Hooper, have two children and three grandchildren. Ferrone also has a son from a previous marriage.

Ferrone is reluctant to talk about his military service, saying he had an easy time compared to what his father and others who fought in the world wars experienced. “In Europe, it was very pleasant because there was nothing going on,” Ferrone says. “You didn’t have to worry about getting hurt. The shooting was over, and you could see the relief on their faces.”

The above appears in the October 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian