A First Lieutenant in the Army, Michael Gasparro went from training soldiers at Fort Lewis, Washington, to leading them on aerial assaults from Firebase Bastogne in South Vietnam.

The oldest of two sons, Mike Gasparro was born in Chicago to Michael and Theresa Fonzino Gasparro. His paternal grandparents emigrated from Senerchia in 1917, and his maternal grandparents also came from Italy.

Gasparro grew up in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, living in a two-flat above his paternal grandparents. Extended family gathered regularly to enjoy his grandparents’ homemade pepperoni, sausage and other foods. “My grandmother would make bread all year long, even when it was 102 degrees,” says Gasparro. “Every September, I would be carrying grapes in for my grandfather to make wine in the basement.”

Gasparro graduated from St. Peter Canisius Grade School and Foreman High School. He had completed three years at Wisconsin State University in Platteville when his deferment ended, and he was drafted into the U.S. Army in July 1969. “Because of Vietnam, nobody was really happy about being drafted, but it was just the way it was at that time,” Gasparro says. “My mother was worried about where I would end up and what would happen to me.”

During World War II, Gasparro’s father fought in the South Pacific with the Navy. All of his eligible uncles were also in the war. One uncle was in the Army during the Korean Conflict. “None of them spoke about the war, ever,” Gasparro says.

Gasparro completed basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and, with his college background, applied to Officer Candidate School, tested and was accepted. During this time, he attended an eight-week course at the Wheeled Vehicle Mechanical School, learning to repair and maintain trucks and other Army vehicles.

Gasparro completed basic training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and, with his college background, applied to Officer Candidate School, tested and was accepted. During this time, he attended an eight-week course at the Wheeled Vehicle Mechanical School, learning to repair and maintain trucks and other Army vehicles.

In January 1970, Gasparro headed to Officer Candidate School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for six months of rigorous, disciplined training. “One of their theories is you always have more to do than you can get done,” Gasparro says. “They know you’re not going to finish every task so they kind of sort people out by who does the most important things first.” He graduated on June 12, 1970, commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in Field Artillery.

Gasparro was assigned as a Training Officer at Fort Lewis, Washington. “I would go out with the trainees and Drill Sergeants and supervise the training of people going through basic training,” Gasparro says.

The soldiers endured extensive physical training and maneuvers, sometimes at night. The sessions included fitness, running a mile in a specific time and learning to shoot an M16, throw a hand grenade and quickly put a gas mask on when going into a gas chamber. Drill Sergeants supervised, and Gasparro went out with them and kept track of all the training records. “I had eight Drill Sergeants, and every cycle we would get about 200 trainees,” he says.

At the end of the eight-week sessions, the soldiers graduated, and only the officers, cooks and maintenance people remained on base. During this two-week period, the barracks were cleaned and repairs were made. “It was like a semi-leave,” Gasparro says. “You would have to go in, but you would have a lot of free time because there were no trainees.” Then, the cycle would begin all over again. “I was there for about a year, so in a period of that year, I probably trained over 1,200 trainees,” he says.

Gasparro enjoyed the job and stayed physically fit. “Every eight weeks, I would go through basic training because somebody had to run with the trainees, do pushups with them — kind of do the same physical activity and go to the rifle range,” he says.

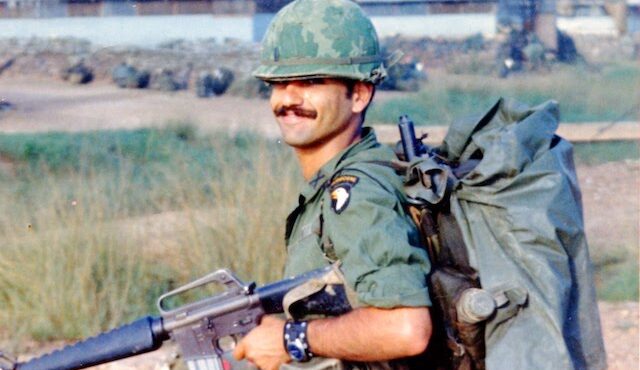

In July 1971, Gasparro received orders to go to Vietnam. He deployed to Phu Bai, assigned to the 101st Airborne as a Lieutenant in Field Artillery. Due to the shortage of officers during the Vietnam War, Gasparro was assigned to be a Forward Observer. “So even though I was an Artillery Officer,” he says, “I ended up going with an Infantry Company.”

Taking part in “aerial assaults,” soldiers boarded helicopters and were dropped into a specific area. Advancing through the “triple canopy jungle,” with layer upon layer of trees covering the area, Gasparro used topographical maps to lead an infantry squad searching for enemy combatants. “My job would be to plot likely targets where I think somebody might be and then call coordinates to those targets in to a field artillery battery, normally six 105 Howitzers,” he says, “and if we did engage somebody, to call back to the artillery battery and have them fire rounds into a target that I determined was where the enemy was hiding.”

Gasparro describes advancing in the jungle. “You just hear something going through the trees. The trees will be moving and you can hear the bullets going by, but you don’t know where they’re coming from,” he says. “One of the best things is to have somebody shoot at you and miss. For an infantry soldier on the ground in the jungle, when somebody’s dropping artillery, it’s like bombs; there is nothing a soldier on the ground with a rifle can do to stop the rounds from coming in.”

Normally, the soldiers stayed out in the jungle for three days — longer if bad weather prevented the helicopters from picking them up and returning them to base camp.

Two days after returning from one mission, Gasparro embarked on another aerial assault, always rotating with a different Infantry Company. He was stationed at Firebase Bastogne, named after the WWII battle. “Most of the Firebases, your living quarters consisted of ammunition boxes or sandbags,” he says.

Spending nights in the jungle required “a whole kind of procedure.” Mechanical ambushes and trip wires were set up in addition to rotating guard duty. “How can you feel when you’re sleeping between two M16s?” asks Gasparro. “You never really get to relax, and you never really fall into a deep sleep.”

Gasparro was stationed at Firebase Bastogne for six months, until the 101st Airborne began withdrawing troops. First Lieutenant Gasparro returned to Chicago, was relieved from active duty in January 1972 and resigned in July 1975. He married Nancy Piasecki in December 1972 and earned a bachelor of science degree in marketing from the Illinois Institute of Technology. Gasparro retired from a successful career in industrial sales with Honeywell Industrial Controls. Now widowed, he has two sons and three grandchildren.

Reflecting on his time in the Army, Gasparro says, “It really is something that shaped me for the rest of my life and has really given me an appreciation for being alive.” He adds, “It has been said that for every one person carrying a rifle, it takes 10 people to support him. That’s true. [The average American] doesn’t realize how hard it is to support a military because people who are fighting have to have everything that they need and be assured that they’re never going to run out.”

The above appears in the September 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian