A bishop in Italy during the first great wave of migration to the Americas, Giovanni Battista Scalabrini founded two religious orders and a lay society to tend to their spiritual and temporal needs.

The year is 1881, and the setting is the Milan train station. A 41-year-old Italian bishop watches as 300-400 migrants — young and old, men, women and children, from different northern provinces — wait to board a train to Genoa. They will all soon be headed to America on a steamship voyage fraught with sickness and danger.

The middle-aged prelate is overcome with sadness as he looks upon the weary, malnourished and ragged throng. Years later, Bishop Giovanni Battista Scalabrini would recall that God caused a “knot in his heart” that day. As a priest and fellow Italian, he asked himself, “What can I do to help them?” The rest of Scalabrini’s life was a purposeful quest to find answers to that question.

The third of eight children, Giovanni Battista Scalabrini was born on July 8, 1839, at Fino Mornasco, near Como. His father ran a small wine shop. Both his mother and father were known for their devotion to their faith.

In school, Scalabrini loved the classics, demonstrated an aptitude for languages and was always first in his class. At an early age, he discerned a vocation to the priesthood. In 1857, he entered the seminary in Como, and he was ordained a priest in 1863. Scalabrini had a strong desire to join the missions in the Far East, but his bishop wanted him to serve as a rector of local seminarians and teach Greek and history.

Four years after his ordination, Scalabrini helped victims of a cholera epidemic near his hometown. Some 50 died, and Scalabrini had to be quarantined. Two more times in his life he would face deadly epidemics. Each time, his commitment to serve the sick trumped the risks to his own life.

In 1870, Scalabrini was appointed as a pastor of a local church, where his religious zeal and administrative talents were noted by his superiors. A mere six years later, at age 37, he was ordained a bishop, soon after which he set out to visit all the parishes in his diocese of Piacenza, a small city in an agricultural area of the Emilia-Romagna region.

Scalabrini’s diocese was large and mountainous, with 250,000 inhabitants in 366 parishes, 200 of which could be reached only by mule or horseback. In many cases, his parish-by-parish visits were the first of their kind in 300 years, and so they were met with enthusiasm. As he traveled, Scalabrini lived “neighbor to neighbor” and shared the poverty of his people. In his 30 years as bishop of Piacenza, Scalabrini visited each parish five times.

As he spoke fearlessly about the importance of faith and morals, he earned many ardent admirers along with some vehement detractors. For instance, members of one Masonic lodge recorded in their minutes that they detested his very presence and his “trickery” as a Catholic priest.

Spurred by the need he saw for religious education, Scalabrini wrote a catechism for kindergarteners, an innovation for his time. Next, he published a magazine devoted to teaching the faith, called “The Catholic Catechist.” In 1877, he wrote a manual on catechism and held a conference on the subject, earning him a reputation as “The Apostle of Catechism.” In subsequent years, Scalabrini came to realize the importance of teaching the faithful in their own language.

As Scalabrini observed the migration of people away from his diocese, he began a lifelong study of the causes and consequences of this multidimensional phenomena. One root issue was the extreme poverty of the Italian field workers and laborers, who faced the real possibility of starvation. This harsh reality led many to the gut-wrenching decision to abandon their homeland in the hope of finding a better life in the Americas. This difficult situation was made worse by dishonest agents who took advantage of those who were desperate to leave.

Boarding the steamship to America was just the beginning of the challenges they faced, as there were no regulations to protect these voyagers. As soon as they stepped on the dock, the migrants were met by padroni or their accomplices, the manutengoli. These labor brokers, often immigrants themselves, acted as middlemen between potential workers and employers. They represented mining and railroad companies and agribusinesses, helping these enterprises find laborers for the hard work of digging earth, laying track, raising livestock and the like. While some were helpful and truthful, others were dishonest in the fees they collected and the promises they made.

Upon their arrival in America, the Italians were greeted by a strong anti-immigrant sentiment, as revealed in an 1896 speech by Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to the United States Senate. Lodge asserted that new measures were needed to thwart the growing danger that the “American race” would be “polluted” by unrestricted immigration with its “low, unskilled and ignorant foreign labor.”

On the spiritual side, Scalabrini recognized that there were far too few Italian-speaking priests for the number of immigrants who were headed toward the Americas.

Although Scalabrini acknowledged the enormity and complexity of the challenges, he repeatedly emphasized the simplicity of the solution: To enact measures that would protect migrants and treat each one as a human being deserving of respect. His resolve in this regard led him to establish a pair of religious orders and a lay society to further that cause.

In 1887, Scalabrini’s proposal for a new congregation was approved by Pope Leo XXIII. The patron saint chosen for the fledgling order was St. Charles Borromeo, the spiritual protector of Milan. Scalabrini’s new missionary order was to be known as the Missionaries of St. Charles. He chose “Humilitas” as its motto, underscoring the importance of humility in serving the poor and needy. In just one year, Scalabrini was ready to send seven priests and three lay helpers to New York.

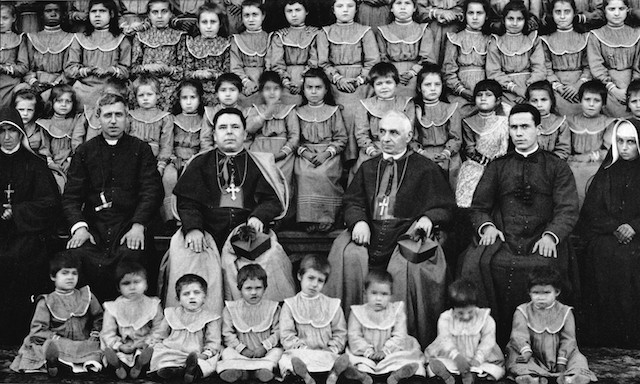

A few years later, Scalabrini realized how valuable it would be to have a congregation of sisters to assist the priests in their mission. The path was paved by Fr. Joseph Marchetti, a young missionary in Scalabrini’s congregation, who made two trips to Brazil in 1894 as a chaplain for the immigrants. After his second trip, Marchetti decided to stay in Sao Paulo and build an orphanage. He, too, immediately recognized that sisters were needed to care for and educate the children.

Marchetti soon returned to Piacenza in search of assistance. When he arrived at his hometown, he convinced his mother, her sister and two young women to accompany him to Brazil. On Oct. 25, 1895, in a solemn ceremony in Scalabrini’s chapel in Piacenza, the women’s branch, known as the Congregation of the Missionary Sisters of St. Charles Borromeo, was founded.

To bolster the work of his missionary priests and sisters, Scalabrini and Giovanni Battista Volpe-Landi, a lay supporter from Piacenza, established the Society of St. Raphael in 1889. This organization of laypeople set up committees in multiple locations, including New York and Boston, as well as the coastal cities of Italy. The aim of the society was to keep “alive in the heart of Italian immigrants, together with the family, the feeling of nationality and affection toward the mother country.”

The society assisted in practical matters: securing temporary housing, exchanging money at fair rates, buying train tickets for further travel, and informing friends or relatives of the immigrants’ arrival.

More than anyone else except the Pope, it was Scalabrini who helped convince the future St. Frances Cabrini to rally her young congregation in support of Italian immigrants in the Americas. Over the ensuing 25 years, Mother Cabrini and her Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart established 67 institutes — including hospitals, schools and orphanages — across the United States and in numerous foreign countries, including Nicaragua, Brazil and Argentina (Fra Noi, March 2023).

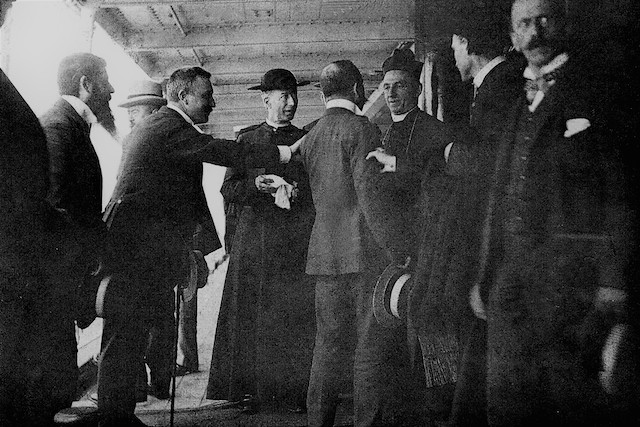

At the urging of his missionary priests in America, Scalabrini became a migrant among migrants, boarding a boat with 1,200 fellow Italians and landing in New York on Aug. 3, 1901. His goal was to study the current state of the Italian-American community and to strengthen the care and ministry delivered to his flock.

While many Americans opposed immigration, the nation’s press generally was excited to cover Scalabrini’s visit. Yet it was the assassination of President William McKinley by an anarchist in Buffalo on Sept. 6, 1901, about a month after Scalabrini’s arrival, that gave him an unexpected opportunity to gain the admiration of the media and, in turn, many American citizens.

The boost in positive press and public sentiment came in the wake of Scalabrini’s bold decision to cancel all his festive appearances and only participate in religious ceremonies while the nation was in distress over McKinley’s gunshot wounds and then in mourning after his death. While Italian immigrants across the U.S. were disappointed by Scalabrini’s decision, the country’s media were impressed. In the predominantly Irish-American city of Boston, for example, an affirming story in the Boston Globe was headlined, “Bishop Scalabrini of Italy Asks the People to Pray for the President.”

Another newspaper glowingly reported that Scalabrini was “a plain, old-fashioned appearing man … [with] merry eyes and benign countenance. One feels that he is sincere in every word and movement.”

The media saw Scalabrini’s cancellations as a mark of respect, and they portrayed Italians as people who could be religious as well as patriotic.

Soon after McKinley’s funeral, Scalabrini met with President Theodore Roosevelt in the White House. The president told the bishop he admired the tough endurance of Italian workers and the quick adaptation of Italian children in American schools. Scalabrini took this occasion to describe the brutal treatment he witnessed at Ellis Island, where a guard hit an immigrant with a huge stick. Scalabrini rhetorically asked the president, “Why do the agents have to be so cruel to workers who come in peace?”

Scalabrini returned to Italy on Nov. 14, 1901, after spending 100 days in the U.S. and traveling 7,000 miles. While in America, he saw for himself the discrimination faced by immigrants and the many difficulties engendered by differences in language, culture and religious customs.

In the late 19th century, millions of Italians immigrated to North, Central and South America to start a new life. In 1904, Scalabrini responded to the request of missionaries in Brazil and journeyed there to encourage the parishioners and strengthen their faith. The itinerant bishop sailed across the ocean with a group of 500 migrants, half of which were Italian.

During his travels to Brazil, Scalabrini witnessed the flourishing of colonies founded by Italian migrants, most of whom settled in São Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul.

After his visits to America and Brazil, Scalabrini’s focus expanded from advocacy for Italians into activism on behalf of all migrants. In his own congregation, two Polish students were trained, ordained and sent to a successful ministry among fellow Poles in Massachusetts.

While Scalabrini’s vision of an international network of assistance for immigrants did not come to fruition, the institutes he founded provided assistance at a time when it was desperately needed. For his accomplishments and zeal, Pope Pius XII dubbed him “Apostle to the Migrants.”

Scores of stories are told of Scalabrini’s devotion to his people. For example, during an exceptionally cold winter famine in 1880, many in Scalabrini’s diocese were starving to the point of death. When his resources ran out, Scalabrini raised money to feed his parishioners by pawning the precious chalice Pope Pius IX gave him and selling the two horses he rode for his pastoral visits. He also turned the first floor of the episcopal residence into a kitchen, offering 4,000 bowls of soup a day to the poor, and emptied his closets to clothe the needy.

Scalabrini’s humility was exemplified by the number of times he turned down offers to be promoted to the position of cardinal. Each time, Scalabrini said no because he felt it would prevent him from more directly serving his people. But his lack of hierarchical ambition did not equate to a lack of tenacity. One observer said that Scalabrini viewed opposition as a sign of God’s approval and that obstacles redoubled his considerable energies.

Immediately following Scalabrini’s return from Brazil to Piacenza in December 1904, he declared plans to visit his diocese for the sixth time and to organize a second national congress in catechesis. Even though Scalabrini was experiencing serious health issues, his announcement came as no surprise to his community since one of his favorite sayings was, “We shall have time to rest after death.”

Despite his resolve, these health challenges prevented him from completing his intended travels. Bishop Giovanni Battista Scalabrini died on June 1, 1905. His last words were: “Lord, I am ready. Let us go.”

During his lifetime, there were miracles attributed to Bishop Scalabrini. Those, along with his personal sanctity and indefatigable service to migrants and the poor, were the cause for his canonization. The effort bore fruit, with Pope John Paul II beatifying Bishop Scalabrini on Nov. 9, 1997, and Pope Francis canonizing him on Oct. 9, 2022.

Today, the Scalabrinians carry on their historical commitment to ministry among Hispanics, Asians, Haitians and other migrant groups. According to the order’s website, there are 1,195 Scalabrinian missionaries working in 39 countries and operating 52 houses for migrants, 13 schools and orphanages, and four hospitals.

True to the ideals of their namesake, the Scalabrinians continue to labor and serve on a grassroots level, focusing on the link between culture, language and faith while continually advocating for the needs of migrants and newcomers of all ethnicities.

Sweet home, Chicago

The religious orders founded by Giovanni Battista Scalabrini established a major presence in the Chicago area and had an enormous impact on the spiritual and cultural life of the local Italian-American community.

Opening provincial houses for the western half of North America in the near west suburbs, they built the Sacred Heart Seminary in Stone Park, Our Lady of Fatima Home in Melrose Park, and Villa Scalabrini nursing home and Casa San Carlo retirement center in Northlake.

They also established a dozen churches across the Chicago area, including Guardian Angel, Maria Addolorata, Our Lady of Mount Pompeii, St. Anthony, St. Callistus, St. Francis Xavier Cabrini, Santa Lucia, Santa Maria Incoronata and St. Michael in Chicago; Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in Melrose Park; St. Anthony in Rockford; and St. Charles Borromeo in Stone Park.

Today, most of those churches are either under diocesan control or closed, and Villa Scalabrini and Casa San Carlo are run as Casa Scalabrini Village by Ascension Living. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel and St. Charles Borromeo church are still run by the Scalabrinians, and the order leases its former seminary to Casa Italia.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian