At least the story starts in familiar fashion: Christian Picciolini’s parents emigrated from Italy to the United States, where they would meet, marry, raise a family and work hard at building a successful small business. But without his parents around to attend his school functions and sports game, Picciolini turned to a heartbreaking place to find his identity: the American white supremacist skinhead movement. He wasn’t even 14 at the time.

“Hell, I had no idea who I wanted to be — aside from Rocky Balboa, of course,” says Picciolini, who has Italian lineage on both sides. (His father was born in Montesano Scalo near Salerno; his mother’s family is from Ripacandida, near Potenza.) “I was insecure, felt disaffected and marginalized, and had been bullied for several years about both my small size and my Italian heritage.”

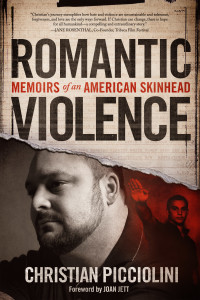

The bracing story of how Picciolini rose to a skinhead leader, and eventually broke away to become a force for peace in society, is detailed in his book “Romantic Violence: Memoirs of an American Skinhead.” In it, Picciolini exposes a shocking array of past behaviors, from attending KKK rallies to his 1992 gig playing in a white power band before 4,000 neo-Nazis in Weimar, Germany.

“By 1992, I was the regional director, leading all the northern U.S. states, for the Northern Hammer Skinheads, the world’s most violent and deadly neo-Nazi skinhead organization,” Picciolini recalls. By that time, his focus was on music and recruiting; “Our record label was selling upwards of 20,000 records from my bands.”

So what was it that motivated Picciolini to turn his life around? As he describes it, becoming a parent made him see his life from a much different perspective — though the consequences were brutal and painful.

“I was a father and married at 19 and a father again at 21; when I held my first son in my arms, I was able to find and reconnect once again with my own innocence, the one I’d lost when joining the movement at 14,” he says. “By 22, I managed to leave the movement and discard my misguided ideology, but it was too late. I had lost my wife and children. They couldn’t tolerate my hateful behavior any longer and left me before I could fully get out.”

Picciolini then spent the better part of a decade learning to ask for forgiveness — and forgive himself. And in 2010, he founded the non-profit Life After Hate “as a way to educate people and also as a support network for people who have left hate groups.” And this year, “we launched a program called ExitUSA, which is actively providing intervention services to help people leave hate groups and racism behind.”

All of this makes Picciolini a leader of a much different kind: One who shows repentant hate group members a way out, and a way to peace. “In order to really understand who you are and be happy with yourself, you must first strive to understand others and walk a mile in their shoes,” he says. “Only then will you understand the true meanings of peace and love. Only then will you find who you are meant to be. Hate is easy. Love takes work. But only one of them has a reward, while the other is certain failure: Kindness is not weakness.”

(christianpicciolini.com)

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian