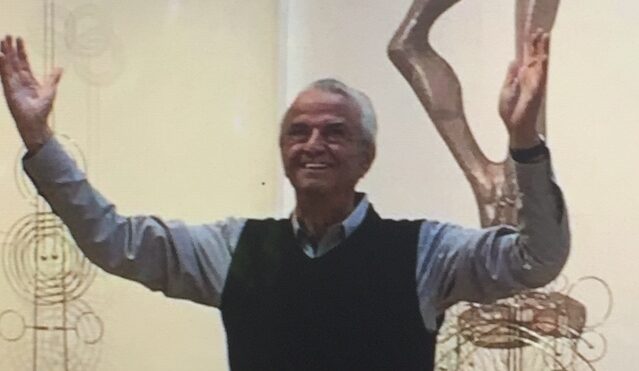

Beginning his professional life as a product designer for Sears, Joseph Burlini took a leap of faith into the world of sculpting and has never looked back.

A practicing artist for 50-plus years, Joseph Burlini has made a name for himself by creating inventive kinetic sculptures and soaring public works.

A native of Morton Grove, Burlini has a degree in industrial design from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and spent six years designing for Sears, Roebuck and Co. before pivoting to making art in a variety of metals and other materials.

Burlini’s works have been commissioned by prominent clients, including The Walt Disney Studios, The Pentagon, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, McDonald’s and the University of Chicago, as well as basketball great Michael Jordan. He taught sculpture at the Illinois Institute of Technology and is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Humanities Service Award.

His artwork was featured in early retrospectives at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago and the Art Institute of Chicago. The Koehnline Museum of Art at Oakton College in Des Plaines held a major retrospective in 2019 with works from all phases of his career.

His artwork was featured in early retrospectives at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago and the Art Institute of Chicago. The Koehnline Museum of Art at Oakton College in Des Plaines held a major retrospective in 2019 with works from all phases of his career.

Burlini talked to Fra Noi about the winding path that led him to become a sculptor, his major pieces, and the crucial support of his wife in pursuing his passion.

Elena Ferrarin: What inspired you to study industrial design and what kind of career did you envision?

Joseph Burlini: A Christian brother I had in high school encouraged me to apply at the Art Institute of Chicago because he felt I had artistic talent. I really did not know what industrial design was, but after learning a little about what it entailed, I felt this was how I could make a living. It’s ironic that I gave it up, but I had to follow my dreams.

EF: You worked at Sears, Roebuck and Co. for six years designing toys, cameras, rifles and other goods. What was that like?

JB: Working at Sears, Roebuck back in the ’60s was a dream job. I was hired as an industrial-product designer, and my work was making detailed renderings of toys, rifles, cameras, dishes, golf clubs, etc., and then going into our product model shop and carving out of wood or clay to create a prototype. Making the three-dimensional products instilled a desire in me to think about being a sculptor, where I could create whatever I wanted. I got to travel to companies that produced Sears products, such as Winchester in Connecticut, Daisy in Arkansas, Whirlpool in Michigan, Bell & Howell in Chicago, to name a few.

JB: Working at Sears, Roebuck back in the ’60s was a dream job. I was hired as an industrial-product designer, and my work was making detailed renderings of toys, rifles, cameras, dishes, golf clubs, etc., and then going into our product model shop and carving out of wood or clay to create a prototype. Making the three-dimensional products instilled a desire in me to think about being a sculptor, where I could create whatever I wanted. I got to travel to companies that produced Sears products, such as Winchester in Connecticut, Daisy in Arkansas, Whirlpool in Michigan, Bell & Howell in Chicago, to name a few.

EF: In your spare time, you began to experiment with drawing celebrity portraits and welding sculptures from steel rods. What inspired you to do that?

JB: From the three-dimensional work I was doing at Sears, I was inspired to purchase a set of welding torches from Sears. I taught myself how to weld in my parents’ garage, and began spending every moment of free time I had experimenting with creating sculptures.

EF: In 1965, you entered a sculpture in the Chicago and Vicinity show at the Art Institute of Chicago, won the John G. Curtis prize and decided to become a full-time artist. What gave you that confidence?

JB: This gave me validation that I did have some talent. This is all I needed to quit my job and pursue what I truly loved. I was working in my parents’ one-car garage and started my new career by going to art fairs to sell my work.

JB: This gave me validation that I did have some talent. This is all I needed to quit my job and pursue what I truly loved. I was working in my parents’ one-car garage and started my new career by going to art fairs to sell my work.

EF: Your wife, Sue Ellen, encouraged you to pursue your passion for art. How important has that support been throughout your career?

JB: The support of my wife when I gave up a promising career at Sears — with a steady salary, profit-sharing, paid vacations and other benefits — to work on my own with no idea of what I would make and no health insurance for a while, meant everything to me. I could not have done it without her unwavering support.

EF: You are especially well-known for your large-scale sculptures. Tell us about your evolution as an artist over the decades. What phases did your art go through, what materials did you use and what kind of experimentation did you do?

JB: Early on in my career, I was invited by the Museum of Science and Industry to have a 10-year retrospective of my work, titled “Rockets to Rainbows.” They especially were interested in my kinetic sculptures. They gave me 4,000 square feet and I filled it mostly with my whimsical machines. After that show, I entered a competition from McDonald’s to create a sculpture that reflected the image of McDonald’s. I won the competition and welded 800 pounds of bronze rods to make a 9-foot-tall sculpture of a happy family on their way to McDonald’s, which I felt represented the core of McDonald’s success. This led me to moving into a 3,000-square-foot studio in a building owned by Richard Don, of Edward Don and Company, the world’s largest restaurant supplier. He became my dearest friend and loving patron until his death. I spent most of my career at the studio in Arlington Heights, where I sculpted my dreams. After the McDonald’s competition, I received a commission from Standard Oil to create a piece in front of their building in Chicago. This was a 23-foot-long bronze titled “Reflections.” This led to multiple commissions from large companies, such as a Canadian firm who commissioned a 68-foot sculpture for the Galleria shopping center in White Plains, New York, which was my largest sculpture. From there, I went on to do a 28-foot sculpture to be placed outside the Wellness Center of Northwest Community Hospital in Arlington Heights.

EF: Were any of them especially difficult to create?

JB: The White Plains, New York, sculpture was, by far, the most difficult, because it was all welded steel and bronze and it had to stand 68 feet high, between the escalators of the shopping center. Going from household sculptures to major public sculptures just morphed without my even realizing it.

EF: Which pieces are you most proud of?

JB: Most artists will say the next piece they do will be their favorite, but my story is a little different. I did a sculpture of a horse before I quit my job at Sears and I gave it to my wife, Sue Ellen. We still have this sculpture and it represents the birth of my fine art career, which has been grounded by the love and support of my wife. I’ve been offered $50,000 for it, but money can’t buy love.

EF: Are you still making art nowadays? If so, what kind, and what inspires you?

JB: After my 50th-year retrospective at Oakton Community College in 2019, I no longer weld. I still do clays and have them cast into bronze. My most recent piece was bronze tulips. They are attached to a memorial bench in honor of our beloved daughter, Jennifer, who passed in 2023 from pancreatic cancer.

EF: What advice would you give young artists who want to pursue a full-time career, like you did?

JB: Follow your dreams! This is your life, go after what you want. It won’t be easy, but it will be authentic and meaningful — and your soul will be fed.

The above appears in the September 2024 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian