Hooked on science ever since his parents bought him a chemistry set at the age of 10, Dr. Louis Ignarro’s life was transformed when he discovered the remarkable impact that nitric oxide has on our overall health.

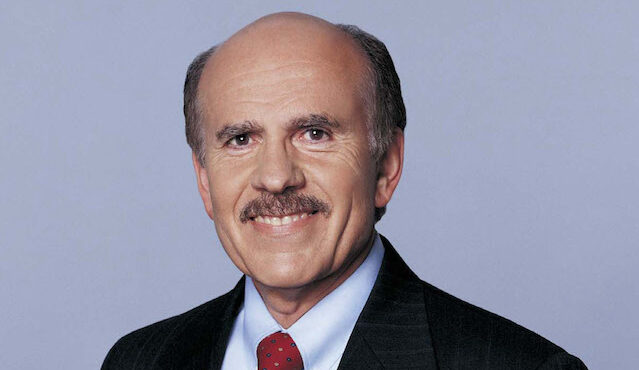

The son of uneducated Italian immigrants, Dr. Louis J. Ignarro won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1998 for a discovery that led to important advances in promoting cardiovascular health.

His memoir, “Dr. NO: The Discovery That Led to a Nobel Prize and Viagra,” was published in 2022. His second book, “The Miracle Molecule,” is expected out this year.

Now a professor emeritus at UCLA, Ignarro talks to Fra Noi about his research, how he found out he won the Nobel Prize and his advice for young scientists.

ELENA FERRARIN: You were born in 1941 in Brooklyn, New York. Tell us about your Italian roots.

LOUIS IGNARRO: My father was born in Napoli and my mother was born in Sicily, and they met in Brooklyn. My dad was a carpenter and my mom wasn’t allowed to work, so she stayed at home to raise me and my younger brother. My father had served in the Italian navy in World War I. His ship was torpedoed by a German warship in the Atlantic and the boat had to dock at New York Harbor. He was a shipbuilder in Italy, and when he saw the way they repaired the ship, he didn’t think it would make it back. So, he and his brother jumped ship and hid in the mountains in New York for about five years, until all was forgiven. The ship never made it back to Italy — it sank on the way back. My mom was one of seven siblings. Her father decided to move to California to be a farmer, but they didn’t have enough money, so they stopped in Brooklyn to save money. That’s when my parents met.

EF: What sparked your interest in science?

LI: I was always interested in science as a child. At age 10, I convinced my parents to buy me a chemistry set and I learned how to do experiments. I wanted to make firecrackers and rocket fuel, and I was able to get my friend’s older brother to go to the pharmacy to get me the chemicals I needed. I maintained my interest in chemistry throughout grade school. When my parents moved to the U.S., they were uneducated — they didn’t even go to kindergarten — and didn’t speak English. When I was a kid, my Italian was great but my English was terrible. When my first-grade teacher said, “He’s going to be handicapped unless he learns to speak and write and communicate in English,” my mom stopped speaking Italian at home. I had to struggle through three grades in elementary school, but eventually all was OK.

EF: What was your academic path?

LI: I thought I wanted to be a pharmacist, so I got a bachelor’s degree in 1962 from the Columbia University College of Pharmaceutical Sciences. But the summer before graduation, I worked in a pharmacy and I decided it was not for me. I was always a scientist at heart. I got a Ph.D. in pharmacology, which is the study of the effects of drugs on the body, from the University of Minnesota, and I did a post-doc fellowship at the National Institutes of Health. Then I took a job at Ciba-Geigy, where I worked for about five years. Then I changed course to do research and teach. In 1973, I became assistant professor of pharmacology at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans, then I moved to Los Angeles in 1985 to teach at UCLA School of Medicine.

EF: Tell us about your research that led to the Nobel Prize.

LI: The discovery was that our bodies produce nitric oxide, a very unique chemical that prevents us from getting cardiovascular disease. I was working on nitric oxide, or NO, before I discovered it was produced in the body.

EF: Your discovery led to the development of drugs such as Viagra and drugs designed for cardiovascular health and athletic performance. What are you most proud of?

LI: One of the criteria for the Nobel Prize is that the discovery has led to benefit humankind. Because of my discovery, we know that if you are deficient in NO — which you can be if you have Type 2 diabetes or you’re overweight and don’t eat balanced meals — that can cause high blood pressure, stroke and heart attacks. The fact that we can prevent that makes me so proud.

EF: Where were you when you found out you won the Nobel Prize?

LI: I had accepted an invitation to go to Nice, France, followed by Naples, Italy to give lectures. When I left Nice to go to Naples, which was only a 45-minute flight, the announcement was made. I didn’t know until the plane landed in Naples. There must have been 200 or 300 people with cameras and flashes going off. The first thing that came to my mind was that the president of Italy must be on the plane with me.

EF: How has your life changed since?

LI: My life changed completely. You suddenly become well-known among all scientists. I had so many opportunities to change my job and be president of this or vice president of that, but I wanted to stay at UCLA to continue my research. I got hundreds of invitations to give lectures all around the world and I accepted as many as I could. I traveled twice a month internationally, up until the COVID-19 pandemic. Now I have started to gradually go back to that, but I am not going to travel as much.

EF: Which destination was most memorable?

LI: Every place in Italy is memorable. Several pharmaceutical companies sponsored my research at UCLA, and one was Menarini. I became a consultant for them, and they invited me and my wife to come to Italy two or three times per year, for 15 years. We almost always went to Capri for a few days. A distant second is Paris.

EF: You have 222,000 followers on Facebook. How did you achieve that?

LI: More recent Nobel Prize winners have as many or more! I have trouble with computers so I had a professional set it up and now I post myself. I also have Instagram. On occasion I have somebody helping me promote sales of my book.

EF: You are also an avid marathoner, right?

LI: My wife, Sharon, convinced us we needed to start running, and I ran my first marathon when I was 64 years old. Then I ran 14 more over the next five years. I ran three marathons in Chicago, that was my favorite. Now I don’t run anymore, I walk slowly.

EF: What advice would you give to young people who dream of making big scientific discoveries like yours?

LI: Try to stay motivated and never give up. It’s just like playing baseball or football — never give up. You’ve got to work as hard as you can, and never let anybody tell you that you can’t do it. I also push people to do original thinking. Don’t follow what other people do — do something new. I always give a quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Do not go where the path may lead. Go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.”

The article above appears in the January 2025 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian