A surgeon serving in Vietnam, he still vividly recalls a four-day stretch during which he and his team toiled to save the lives of a couple dozen severely wounded Marines.

A surgeon serving in Vietnam, he still vividly recalls a four-day stretch during which he and his team toiled to save the lives of a couple dozen severely wounded Marines.

Paul Rubino was born in Bitritto, a small town near Bari, Italy. When he was 12 years old, he and his mother, Domenica, immigrated to Chicago where his father, Vincenzo, had been working as a candy maker. The family settled into a third-floor apartment on Grand Avenue and May Street, above Taccogna Foods, now known as Bari Finer Foods.

The close-knit neighborhood was largely Italian, many from Bari. Everyone looked out for one another and helped each other. “When you live in a strange world, strangers become friends,” says Rubino.

Rubino entered Santa Maria Addolorata grade school in the sixth grade. “We were 25 of us, all Italians, all immigrants. We were taught how to speak English for one semester,” Rubino recalls. “Then we went into the regular class. The nuns were very devoted to making sure we learned English.”

Education was very important to Rubino’s mother, who only had a fourth grade education in Italy. His parents found a way to send him to St. Ignatius High School. “For a woman who hardly knew this country, how she made the decision to send me to St. Ignatius, I don’t know,” Rubino wonders. “These Italians, they talk to each other and they find out the best place to go.”

Many of his classmates planned on attending college to improve themselves and Rubino followed suit. “If they’re going to go to college,” he thought, “well I’m going go to college, too.”

He graduated from Loyola Medical School, interned, and spent a four-year residency in general surgery at Cook County Hospital and West Side Veteran’s Hospital. He was drafted into the Army while in the final year of his residency and obtained a deferment to complete the term.

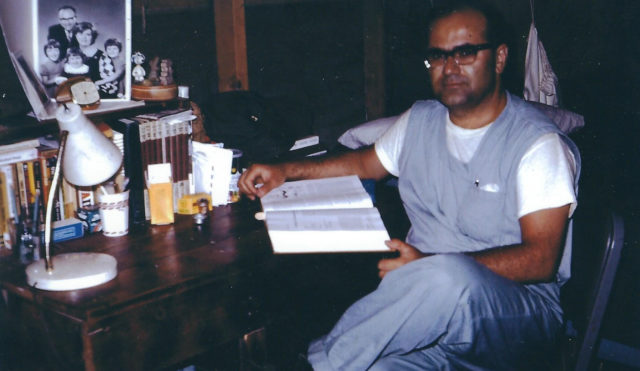

The deferment gave Rubino the opportunity to join the Navy in July 1968. He was stationed at Great Lakes Naval Base for one year, where he treated soldiers recovering from combat injuries in Vietnam. Rubino was a full-fledged surgeon by that time and received no basic military training. His captain said, “Anybody that has more stripes than you do, you salute them. If they have less stripes than you, he’s gonna salute you first, so you just return the salute.” “That’s the honest truth,” Rubino chuckles. “That was my whole training.” He explains, “Doctors are not soldiers. We get big names like lieutenant or lieutenant commander, but that’s just an honor.”

Before deploying to Vietnam in October 1969, Rubino spent one week at Camp Pendleton in California where he attended lectures on tropical diseases and learned to triage large numbers of critically wounded men. He also observed a mock war with Marines fighting each other.

Rubino was with the 1st Medical Battalion as part of the 1st Marine Division stationed at a camp a few miles outside of DaNang. Six doctors shared a hooch, a type of hut that served as their living quarters, with local women called “mama sans” who cleaned for them. The camp housed a priest and contained a chapel, 12 hooches, a separate building for the cafeteria where the doctors ate three meals a day and a hospital that was a converted Quonset hut.

The 30-bed hospital included six operating rooms with ample supplies and medical equipment. About 25 doctors representing various specialties staffed the camp. “A patient got treated very well under the circumstances,” says Rubino.

Nestled at the base of a mountain, the camp was protected from mortar fire and never got hit. As it was a guerilla war, the order was “search and destroy” and “shoot anything that moves,” a strategy determined by politicians in Washington. He heard rockets his first night there. “I was a little scared,” Rubino says, “but after a while you learn to live with it. There’s one sound as rockets come in; there’s another sound going out.”

Pagers in each hooch notified the doctors of incoming wounded, and helicopters flew in routinely with casualties. The doctor on call quickly evaluated the patient and paged the appropriate doctor depending on the condition of the patient and the type of treatment needed. Rubino’s area of expertise was abdominal injuries. The soldiers were treated with antibiotics and pain meds as doctors worked to stabilize them.

One night in December, the pagers blared that massive casualties were coming. “I’m a doctor; that’s what they sent me there for,” explains Rubino. “You are there to save human lives.” A truck carrying a couple dozen Marines had hit a landmine, catapulting 20 feet into the air and exploded into flames upon crashing to the ground. All the doctors rushed to the emergency room as helicopters arrived with the severely injured soldiers. Their triage training kicked in as they swiftly evaluated each man. “Every doctor looked to see what was going on,” Rubino recalls. “I’ll take this patient, you take that one.” Far too many went directly to the morgue.

Spines were crushed and arms and legs were shattered by the explosion. Many of the Marines lost limbs. Abdominal wounds exposed shredded organs. Soldiers struggled to breath with caved-in chests. The scene was gruesome as the doctors sprang into action, taking the worst patients first. All six operating rooms were in use at the same time. Others patients waited on carts for their turn. The doctors toiled non-stop for four days to stabilize the soldiers. “You don’t think about sleeping,” says Rubino. “You’re there to take care of the next patient.”

Once the soldiers were out of immediate danger, they were transferred to hospital ships in DaNang Harbor.

Twice a week, Rubino volunteered at a local civilian hospital in DaNang, where he performed surgery with the assistance of Vietnamese doctors and also taught medical students from Saigon. The hospitals were very primitive, with beds often being shared by two patients.

Rubino’s wife, Ann, was pregnant with their fourth child when he was in Vietnam and they wrote daily. The doctors sometimes watched movies in the evening and had pig roasts once a month. They often wondered out loud why they were in Vietnam. These young people being maimed and killed, and for what? “You start blaming the politicians for creating the war,” Rubino recalls.

Lt. Commander Rubino spent six months in Vietnam, returned to the United States in April 1970 and was stationed at Great Lakes until his two-year term was finished. Upon discharge, he joined the Family Medical Group in Joliet, working as a surgeon until retiring in 2003.

He and his wife have five children and six grandchildren. Rubino keeps in touch with many of the doctors he served with. His photo and memorabilia are on display in the Italian American Veterans Museum at Casa Italia in Stone Park.

“Helping the Marines was great for me,” Rubino says. “Yet, looking back, I honestly feel we really did not belong there. It was too bad Truman didn’t listen to Ho Chi Minh when he asked for help.”

The above appeared in the March issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian