A trek along a medieval pilgrimage route in Italy moved Chandi Wyant from personal tragedy to spiritual triumph and an award-winning memoir.

Italy has no shortage of stunning historic roads (think Appian Way), but when it comes to pilgrimage routes, few can match the Via Francigena. It owes its existence to a little-known abbot named Sigeric who, after John XV named him Archbishop of Canterbury, forever marked the trail by writing about the 80 mansions he stayed in (and perhaps partied at) along the way.

Fast forward to 2009, when historian and world traveler Chandi Wyant tackled the path herself. Given her English lineage, the road’s terminus in Canterbury may have tugged at her unconsciously. But it was her lifelong spiritual connection to Italy and a stunning double-dose of bad news that compelled her along the path. After an emergency surgery during an Italian vacation, Wyant returned home to the States, feeble and anxious, to finalize her divorce.

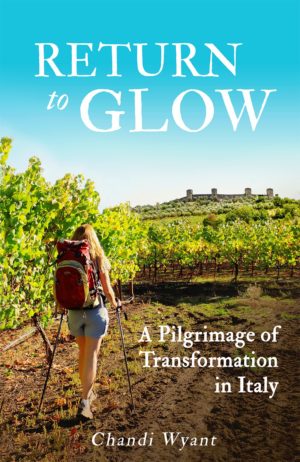

As her ex walked away, Chandi felt the pull to walk Italy. Despite strong reservations, she launched a fundraiser and took the trek — which transformed her with the force of a sunset illuminating Cinque Terre’s rugged coast. From Fidenza in the north to Rome in the south, the 264-mile, 40-day journey is chronicled beautifully in Wyant’s new book “Return to Glow: A Pilgrimage of Transformation in Italy.” (For more, click here.) Prior to its publication, the book captured third-place honors in the 2015 National Association of Memoir Writers contest.

Lou&A caught up with Wyant as she was packing boxes to move to — where else? — Italy to continue her journey of transformation.

Lou&A caught up with Wyant as she was packing boxes to move to — where else? — Italy to continue her journey of transformation.

Lou&A: So let’s start with the name “Via Francigena.” And why walk this route when you had your choice of less grueling paths worldwide?

Chandi Wyant: It means “coming from the Frankish lands.” It never really occurred to me that I would do this anywhere else. Italy represents for me my true spirit. I think it’s because I’m a passionate person stuck in an Anglo-Saxon culture. Life is too short to be boring. Having a full experience means not holding back, and allowing yourself to experience life fully and deeply. That’s the way Italians live. There’s no permission for that in Anglo-Saxon culture.

L&A: You’re also a fluent Italian speaker. How do you explain your affinity for Italian time, place and culture?

CW: The Italy connection started when I was 19 and budget backpacking in Italy. That first day I just felt more at home than I’d ever felt, which happens to a lot of people. [Laughs.] It’s not a new thing: The fatal charm of Italy.

L&A: How was that journey different from this one?

CW: The first trip, if you can believe it, cost $10 a day in the 1980s. I’d eat bits of cheese while sitting in the piazza. To get over for this pilgrimage, I had to do a crowdfunding campaign. Once again, it was a minimal budget with minimal items in the backpack. But this time, the physical aspect of it was quite hard for me and that’s because my body had not fully recovered from my illness. I was pushing myself to do this and I could not accept that I wasn’t better after six months. I didn’t have the body I had before. I thought I was the most pathetic pilgrim on the path.

L&A: So what made you pull the trigger?

CW: The life coach I call Gregg in the book became a mentor. I was battling voices in my head and in my heart — and they were not agreeing. My head said, “This is a cockamamie idea,” and my heart said, “But I’ve received this message.” Gregg was very firm in saying that it was necessary to approach life from the heart as opposed to the head. I would remind him of the practicalities and the things that needed to be done and he’d say, “Yes: You do have to attend to the details. But you have to follow you heart first.”

L&A: Too many books are written by people in mid-life crisis who take a wild road trip, have a wild time and come back claiming spiritual enlightenment. But that’s clearly not what’s going on here.

CW: It was much harder than I admitted to myself. I said to myself, “I backpacked in Nepal at 10,000 feet when I was 21: I can do this!” But there was this struggle to accept that I was in a different place physically and there were stretches of the route I simply could not do. I had to learn to be gentle with myself and take some rides. I had to develop trust that I would be taken care of. I would be on the road, flagging down a car and every time someone stopped, it was a single man. [Laughs.] So I had to learn to work with faith, with trust — and spiritual experiences started to escalate toward the second half of the trip.

L&A: So which terrain was tougher: the one by land or the one inside?

CW: I started off with a lot of demons in my head and worked on purging those as I went. They particularly seemed to dissipate after Siena. Certain things happened — and we shouldn’t give everything way — but my heart just started opening a lot more, and the closer you get to Rome, the more you can stay with nuns and monks. I had wonderful and profound experiences with the nuns I stayed with in the Lazio region. Higher up in Italy, it’s more of the hostel-type accommodations.

L&A: It’s 2017. Do you still have the glow?

CW: Yes. It’s not just a glow where I am enlightened now and this experience fixed everything. It really has put me on the path I’m meant to be on. I’m much clearer on how to connect with my heart and true spirit.

L&A: And how will you keep it?

CW: Doing a pilgrimage or a quest doesn’t fix everything. I still struggle with catching negative thoughts and turning them around. I have no goal of being enlightened. I am very average. But the pilgrimage gave me an idea of my resilience. And the experiences from the pilgrimage are in my cellular memory. They are accessible to me when I need extra strength, when I want to be more openhearted.

I also feel like I’ve developed a large amount of compassion. When you’re really in grief and your heart gets busted open, you find a lot more compassion. I’ve noticed much more understanding since that time, and when I start struggling with things, I can remember my resilience, and how I overcame the physical and emotional pain.

The above appears in the May 2017 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian