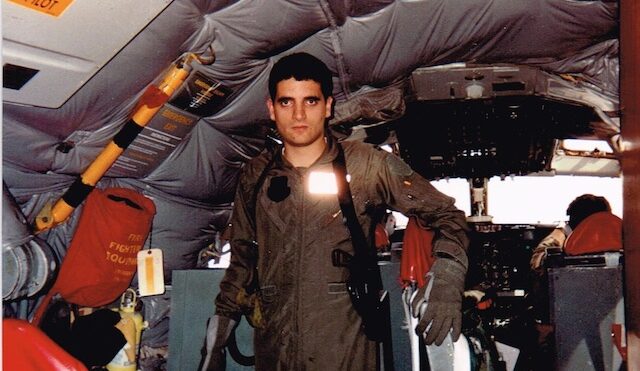

A navigator on a KC-135 Stratotanker for the Air Force, Peter Belmonte’s job was to usher aircraft toward what he called “controlled collisions” with planes that required refueling.

The middle of three children, Peter Belmonte was born in Waukegan, Illinois, to Louis and Eva Spizzirri Belmonte. His mother emigrated from Marano Marchesato in Calabria, and his father’s ancestors were from that same region.

Belmonte’s paternal grandmother lived with them, and he saw relatives from both sides of the family weekly. “Sunday was the day of choice,” Belmonte recalls. “Somebody was dropping by somewhere.” His mother made spaghetti with a sauce that cooked all day, in addition to other specialties. “When I was a kid, my mother’s lasagna was my favorite,” he adds.

Belmonte graduated from Greenwood Grade School, Jack Benny Junior High School and Waukegan East High School, the latter in 1979. He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force during his senior year under a program that allowed him to graduate and then go on active duty. Always a history buff, Belmonte became interested in military history after researching a Civil War sword he found in his grandmother’s closet. That interest, along with his fondness for playing Army as a child, inspired Belmonte to enlist.

He completed basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas; learned to be a pay clerk at Sheppard AFB, Texas; and was stationed at Grissom AFB, Indiana, as a military pay clerk. “It was a good, clean office job,” Belmonte says. While on duty, he spoke with aircrew members from KC-135 Stratotankers and thought, “Gee, this looks more interesting than being a pay clerk. I’d like to fly.” He decided to become a navigator. Belmonte took college classes while off duty, applied for and was granted an ROTC scholarship at Purdue University and was released early from active duty to pursue his degree. He graduated with a bachelor of science in mathematics and a commission as second lieutenant in the Air Force. Belmonte then returned to active duty and attended navigator school at Mather AFB, California.

He completed basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas; learned to be a pay clerk at Sheppard AFB, Texas; and was stationed at Grissom AFB, Indiana, as a military pay clerk. “It was a good, clean office job,” Belmonte says. While on duty, he spoke with aircrew members from KC-135 Stratotankers and thought, “Gee, this looks more interesting than being a pay clerk. I’d like to fly.” He decided to become a navigator. Belmonte took college classes while off duty, applied for and was granted an ROTC scholarship at Purdue University and was released early from active duty to pursue his degree. He graduated with a bachelor of science in mathematics and a commission as second lieutenant in the Air Force. Belmonte then returned to active duty and attended navigator school at Mather AFB, California.

After completing survival training at Fairchild AFB, Washington, and KC-135 training at Castle AFB, California, Belmonte was assigned to the 380th Air Refueling Squadron at Plattsburgh AFB, New York.

The KC-135 Stratotanker refuels military planes while both are in the air. As navigator, Belmonte’s duty was to sync up his tanker with the receiving aircraft. “I had to make sure the airplane was at the correct place at the correct altitude at the correct time to meet up with the plane we were going to get fuel to,” Belmonte says. “Basically, every time you do air refueling, it is literally a controlled midair collision.” The planes touch while the fuel is pumped, which changes the center of gravity as well as weights and balances. “It’s a complicated process,” Belmonte says. “Everybody’s got to pay attention.” Weather conditions and the skill of the pilots make it challenging, and there are times when two planes collide and crash. “You have to be really diligent,” he says.

Preparation began the day before a mission with a meeting of the four-man crew: pilot, co-pilot, navigator and boom operator. They had to know where they were going and how much fuel they needed. Belmonte looked at the mission requirements and used a “whiz wheel” — a small manual computer like a circular slide rule — to calculate course, distance, timing and other details. He drew a chart indicating the course they were to fly and briefed the entire crew. The next morning, they grabbed their life-support equipment, caught a crew bus to their plane, got the weather briefing for the entire route of the flight and performed their pre-flight check. All of this took about two hours. If the weather cooperated, they received clearance and took off for the refueling rendezvous. “I was the one responsible for overseeing timing,” Belmonte says. “Your main concern was to get the fuel to the aircraft so that aircraft could either recover safely or continue on their mission, drop bombs or whatever they’re going to do. There are airplanes all over the place and not a lot of talking.”

During his 20-year military career, Belmonte served as navigator, senior navigator and master navigator on the KC-135. He was also a staff officer and instructor. He taught newly commissioned lieutenants to become KC-135 navigators and served as a combat navigator flight instructor. “I was a highly experienced instructor, and I went to school to learn how to train other highly experienced navigators to become instructors,” Belmonte says. “It’s like another rung in the experience ladder.”

Belmonte deployed overseas many times on temporary duty lasting four weeks, six weeks or sometimes longer. Tanker task forces are based in various places around the world to handle the refueling of whatever military aircraft needs it. In addition to Alaska, Hawaii and Guam, these assignments took him to Asia, Europe and the Middle East. He spent time in England, Germany, Italy, Greece, Spain, the Azores and Okinawa. “Those were the days (in the ’80s and ’90s) when Europe was very highly occupied by the United States,” Belmonte says. “It was kind of fun to go with your crew to Europe, but I didn’t like to leave my family for six weeks.”

On Nov. 1, 1990, Belmonte deployed to Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Shield, flying more than 40 missions through Jan. 15, 1991. He also flew 39 combat support missions in Operation Desert Storm from Jan. 17 through the cease-fire on Feb. 28. He was based at King Khalid International Airport, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, with the 1703rd Air Refueling Wing. Desert Shield involved regular stretches of flying and time off. Desert Storm was more intense, with no typical schedule. “You’d have your mission planning, pre-flight take off, do your mission, land, post-flight, try to get maybe a bite to eat, some coffee, try to get some sleep and start over again,” Belmonte says. “You slept when you could, and you ate when you could.”

Under normal circumstances, there is constant communication during the refueling process, with air traffic controllers and with the aircraft receiving the fuel both during refueling and after the planes separate. In a combat situation, there is no talking. “We know where we are supposed to go, and after we took off from the tower, we didn’t talk to anybody,” Belmonte says.

He recalls his first combat support mission flown. It was on Jan. 17, 1991, and his tanker was rendezvousing to refuel two F-4 Gs, which had dropped ordnance on an anti-aircraft site. “I watched them come off the target, off our wing. Nobody said anything. They came up, got their gas, left and we went back. Nobody said a word,” Belmonte says. “It went very smoothly. In the background of all that, you see everything burning, smoke and flames. It was going well — for us at least.”

The King Khalid air base was under SCUD [missile] attack almost nightly from the start of the war, and at times Belmonte took off and landed amid missile fire. “We’d watch our Patriot batteries engage, launch and blast the SCUDs out of the sky,” he says. “I saw it a couple of times while I was flying in, which was a very dicey thing.” Once, just as Belmonte’s tanker was ready to take off, they got word that SCUDs were inbound. The man in the aircraft control tower said, “You’re pretty much cleared to do as you want, but I’m leaving!” The tower controller sought shelter, and Belmonte’s plane took off.

Belmonte kept a journal of his Desert Storm combat support missions, in which he named the types of planes refueled, recorded details of the rendezvous and tallied the total hours it took. “We just flew and flew and flew with no accidents,” he says, “thanking the Lord for us and nobody else getting hurt and things like that.”

An entry from Mission 24, Feb. 8, 1991, involving 12 A-10s and an EC-130, reads: “We were refueling the A-10s at low altitude and they kept coming at us. We were having a hard time squeezing in the EC-130, who was waiting patiently orbiting over Kuwait. I suspect the A-10s were getting gas and then going to kill [Iraqi] tanks. I don’t recall how many different flights came up. The EC-130 finally was able to come and get his gas. So, at least 13 satisfied customers, not including the ground troops who eventually benefitted from the diminished tank count.”

The A-10 provided close air support for friendly ground troops, attacked armored vehicles and tanks, and provided quick-action support against enemy ground forces. The EC-130 was an electronics warfare platform supporting ground troops.

Belmonte retired from the Air Force in 2003 as a major and was awarded the Air Medal for the combat support missions he flew. He has worked for the Department of Defense as a flight manager distributing flight packages to aircrew around the world and is now employed with a federal government agency that supplies aeronautical information to pilots.

He and his wife, Pamela Mai, have six children. Belmonte has a master’s degree in history and has taught as a college adjunct instructor in addition to his full-time job. He has researched and written several military history books, mostly about Italian Americans in World War I.

Reflecting on his career, Belmonte says, “Overall, it was very enjoyable for me. It was just very interesting and satisfying in unusual ways.” About being an instructor, he says, “I had to know a little bit more than the student so I had to stay a step ahead and learn. Each time, I learned more about the airplane and about the mission, about navigating.” Regarding his time flying combat support missions during Desert Storm, Belmonte says, “It’s pleasurable to help our forces do what they have to do safely, so that was a satisfying thing.”

The above appears in the January 2022 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian