On Dec. 1, 1958, a fire tore through the Our Lady of Angels School on Chicago’s West Side. Ninety-two of the school’s 1,600 students perished in the conflagration along with three nuns, and many more suffered from burns and smoke inhalation or were injured when they jumped from windows to escape.

The worst school fire in American history, it devastated the largely Italian-American community and left lasting physical and emotional scars on survivors and family members of the victims. It also created bonds of friendship and support that endure to this day.

“I remember who I went to grade school with but I don’t remember who I went to high school with,” says Larry Furio, a survivor of the fire. “That sort of thing stays with you forever and it brings people closer together.”

Those bonds were renewed at a 60th anniversary Mass at 5 p.m. on Dec. 2 at Holy Family Church, 1080 W. Roosevelt Road, Chicago. The service was celebrated by the Rev. Michael Gabriel, with Furio and fellow survivor Frank Giglio reading the names of the victims after the eulogy. (847-209-8794)

OLA Fire expert Jim Gibbons presented a special program to mark the 60th anniversary at 10 a.m. on Dec. 1 at the Chicago Fire Academy, 558 W. De Koven St., Chicago. The free program was sponsored by the Fire Museum of Greater Chicago. (877-225-7491)

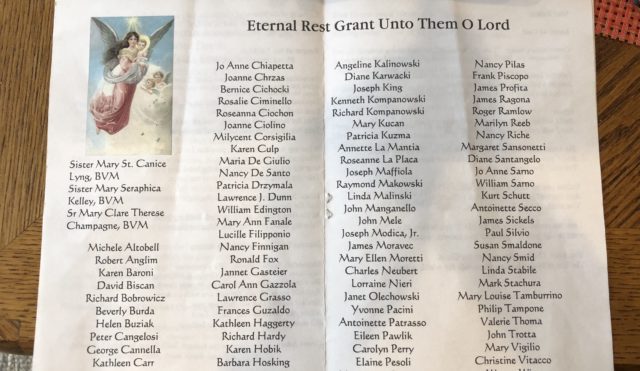

Remembering Our Angels

— Submitted by the survivors of the Our Lady of Angels fire and the friends and family members of those who lost their lives.

On Dec. 1, 2018, we will mark the 60th anniversary of the fire at Our Lady of Angels Grammar School on Chicago’s West Side. One of the deadliest fires in American history, the blaze shocked the nation. On that day, we would like to remember and honor our 92 Angels and our three BVM nuns:

Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng, BVM, Sister Mary Seraphica Kelley, BVM, Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne, BVM, Michele Altobell, Robert Anglim, Karen Baroni, David Biscan, Richard Bobrowicz, Beverly Burda, Helen Buziak, Peter Cangelosi, George Cannella, Kathleen Carr, Margaret Chambers, Aurelius Chiapetta, Jo Anne Chiapetta, Joanne Chrzas, Bernice Chichocki, Rosalie Ciminello, Roseanna Ciochon, Joanne Ciolino, Milycent Corsigilia, Karen Culp, Maria De Giulio, Nancy De Santo, Patricia Drzymala, Lawrence J. Dunn, William Edington, Mary Ann Fanale, Lucille Filipponio, Nancy Finnigan, Ronald Fox, Jannet Gasteier, Caron Ann Gazzola, Lawrence Grasso, Frances Guzaldo, Kathleen Haggerty, Richard Hardy, Karen Hobik, Barbara Hosking, Victor Jacobellis, John Jajkowski Jr., Angeline Kalinowski, Diane Karwacki, Joseph King, Kenneth Kompanowski, Richard Kompanowski, Mary Kucan, Patricia Kuzma, Annette La Mantia, Roseanne La Placa, Joseph Maffiola, Raymond Makowski, Linda Malinski, John Manganello, John Mele, Joseph Modica,Jr., James Moravec, Mary Ellen Moretti, Charles Neubert, Lorraine Nieri, Janet Olechowski, Yvonne Pacini, Antoinette Patrasso, Eileen Pawlik, Carolyn Perry, Elaine Pesoli, Mary Ellen Pettenon, Edward Pikinski, Nancy Pilas, Frank Piscopo, James Profita, James Ragona, Roger Ramlow, Marilyn Reeb, Nancy Riche, Margaret Sansonetti, Diane Santangelo, Jo Anne Sarno, William Sarno, Kurt Schutt, Antoinette Secco, James Sickels, Paul Silvio, Susan Smaldone, Nancy Smid, Linda Stabile, Mark Stachura, Mary Louise Tamburrino, Philip Tampone, Valerie Thoma, John Trotta, Mary Vigilio, Christine Vitacco, Wayne Wisz.

— Submitted by Carmen Mele, O.P.

Most summers when visiting my family in Chicago, I have lunch with a former teacher and a few Our Lady of the Angels School classmates. The table conversation includes updates and memories. Always the discussion turns to “the fire.” There is no need to introduce the topic with another adjective. We do not say, “the school fire” or the “the OLA fire.” For our generation of OLA students in the late 1950s, those two words have a unique meaning. The catastrophic fire burned down our school and killed 95 of our schoolmates and teachers. It etched a memory in our minds more distinctive and permanent than a body tattoo.

Every one of the 1,600 or so students enrolled at the school lost a family member or friend. Most of us lost multiple companions. My brother, John Joseph Mele, died in his fifth-grade classroom, which turned into a toxic smoke chamber. Our friend, George Cannella, with whom we played baseball after school, perished in the same place. Many of my friends had siblings who also died. Joseph King, the brother of Bill King, a future Boy Scout mate, likewise was a fifth grade victim. (27 students — 50 percent of the class — and also their teacher, Sr. Mary Clare Therese, lost their lives in that classroom.) Karen Hobik, the sister of my pal Wayne, died in the eighth-grade classroom, which became an incinerator.

The fire left emotional marks on its survivors. All of us were probably chased by nightmares for years. Likewise, we became anxious well into adulthood when entering closed places. No doubt the fire branded each one in a unique way as well. In our conversations at those summer luncheons, we sometimes compare notes about who feels this way or that as an effect of the fire. I cannot say that I have had regularly recurrent thoughts of it for decades. I have read, however, how some survivors remain almost traumatized.

There is a group that was no doubt more deeply affected by the fire than any other. None of its members inhaled smoke nor were they seared by flame. Yet each of them suffered the ravage of the fire in inconsolable ways. These were the women and men who lost their children. Because they did so valiantly, I would like to dedicate the rest of this article to them. By now, 60 years after the fateful day, they are with few exceptions dead. Nevertheless, they lived with more sorrow than any of us OLA students will ever bear. We may continue having frightening recollections and unfillable wishes that the blaze would have been contained or that the firemen could have rescued more children. A few of us may still suffer pangs from debilitating burns. But the 90 or so sets of parents have taken to their graves a torturing emptiness. They lost outgrowths of themselves cherished more than an arm or leg.

This is not the first time that these people have been credited for virtue. They are part of the cohort that newsman Tom Brokaw labeled “the greatest generation.” To attain this recognition, they made arduous sacrifices. They overcame the encumbrances of poverty during the Depression. They fought and defeated — whether on the frontlines or the home front — tyrannical aggression in World War II. And they proceeded to build a nation of peace and prosperity in the face of Communism’s brutal idealism. Of course, they had faults both as individuals and as a collective, but these were far outweighed by a faith that overcame egotism.

I can only tell the story of our own mother, Angela. At the time of the fire, she was a recent widow who returned to work to support us three children. She waitressed at a neighborhood restaurant a few blocks from our grandparents’ two-story where we lived. On the afternoon of the fire, I walked home after exiting a smoking classroom by means of a fire escape. I met my mother running from work. If I recall correctly, she asked where my brother and sister were. When I said I did not know, she told me to go inside as she continued to race toward school. Our sister, Mary, turned up later with a burn on her leg. She had boosted herself upon a radiator to reach a firemen’s ladder and escape her flaming classroom. Our mother came back toward evening with no word about our brother.

I can only tell the story of our own mother, Angela. At the time of the fire, she was a recent widow who returned to work to support us three children. She waitressed at a neighborhood restaurant a few blocks from our grandparents’ two-story where we lived. On the afternoon of the fire, I walked home after exiting a smoking classroom by means of a fire escape. I met my mother running from work. If I recall correctly, she asked where my brother and sister were. When I said I did not know, she told me to go inside as she continued to race toward school. Our sister, Mary, turned up later with a burn on her leg. She had boosted herself upon a radiator to reach a firemen’s ladder and escape her flaming classroom. Our mother came back toward evening with no word about our brother.

It was the longest night of our lives as it was for all the families who had lost children in the fire. Around 8, if my memory serves well, we received a call from our uncle at the county morgue. He said that he had identified our little brother, who we called “Skip.” As we had dreaded to hear, he was dead. There would be no soothing from the horrors of that pronouncement for a long time.

Our mother was embittered by the loss as perhaps all the parents of victims were. Almost 40 years later, I remember speaking with another mother who lost her son. We were talking about the celebrated archbishop of Chicago, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin. I said something complimentary, but the distraught mother corrected me. She was upset because one year Cardinal Bernardin declined to celebrate the fire’s annual memorial Mass.

Few if any of the parents, however, became vindictive. As far as I know, there were no suits demanding millions from the archdiocese. Most accepted, I believe, as our mother did the blameless explanation of faulty electrical wiring as the cause of the fire. They were not being deliberately naïve or obsequious. They just trusted the archbishop, Cardinal Albert Meyer, and OLA’s pastor, Monsignor Joseph Cussen. Not without reason people have become cynical about priests, yet no one at the time doubted the integrity of these churchmen.

The parents showed excellence in several ways beyond not allowing anger to dominate their lives. They continued raising their families in love. When we survivors wondered why we did not perish, their gentle words and embraces comforted us. They also helped rebuild the school. In less than 2 years, children again lined Iowa Street every morning preparing to enter their state-of-the-art building. Finally, they kept believing in God’s goodness. They might have left the Church and all religion, but they found strength in Jesus’ promise: “’… no one who has given up house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or lands for my sake and for the sake of the gospel … will not receive a hundred times more now in the present age: houses and brothers and sisters and mothers and children and lands, with persecutions, and eternal life in the age to come.’”

In his Letter to the Romans St. Paul, writes: “…all things work out for good for those who love God…” We might name the good that came from the grief over those dead children. The OLA fire moved the whole country to improve school conditions and enforce fire codes. There has never been a school fire since then with anywhere near its casualties. It brought the community together as never before. Everyone, it seemed, worked to rebuild the school. Most of all, it made the survivors of the fire and certainly the parents of its victims sensitive to the pain of others. We know what it is like to suffer the sudden loss of a loved one. We are familiar with having our lives drastically changed from one day to the next. Remembering the hollowness felt on those days and for years afterward, we can respond to similar pain and sorrow with compassion.

At the end of “The Bridge of San Luis Rey,” author Thornton Wilder writes some captivating words that summarize the lives of his characters. The novel tells the stories of five casualties of a fallen bridge outside Lima, Peru. The last lines apply just as well to the parents of the OLA fire dead. Wilder writes:

“We ourselves shall be loved for a while and forgotten. But the love will have been enough; all those impulses of love return to the love that made them. Even memory is not necessary for love. There is a land of the living and a land of the dead and the bridge is love, the only survival, the only meaning.”

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

So horribly sorry for your loss, how 60 years later it still hurts. That neighborhood was destroyed, from all i have read, and from what you lived. It tore the heart out of it.

I live all the way in Southern New Jersey, near Philadelphia. Yet the fire at Our Lady of the Angels School is not unknown here. I was friends with the sister of a victim in Rm. 211. A lay teacher from OLA, present at the time of the fire, taught at Paul VI hIgh school with my pastor. She couldn’t talk about the fire. At work, I met a relative of one of the fire victims. who was amazed when I asked if he had family in Chicago. I was self-conscious when I told him why. His last name was an uncommon Italian name, and I knew it from the book ‘To Sleep with the Angels’.

Just found your article. … I’m a survivor. This is one of the most endearing tribute to a group of people I believe I’ve ever read, and one of the first that I’ve read in tribute to our parents. My Dad was CPD in that district and served in WW II and Korea. My mother had 5 of her 7 children by this time and was carrying her sixth. THANK you and God bless. I’m shaking as I write this. …The memory never leaves.