Imagine you just finished huffing your way up to our floor, the sixth and topmost of our South Bronx tenement, 95 steps above the torrid sidewalk of East 148 Street, late on a summer afternoon of 1958. In the first apartment on the landing, jolly old Maria Torlona the Egg Lady, whose door is open, might well try to sell you a carton of her wares — or even a case — fairly cheap.

Next door to Maria and her cache of “farm-fresh” eggs is the residence of blue-haired Mrs. Pugliese and her tall feisty brunette daughter, Gloria. That young beauty is being courted by an amateur singer my mother dubbed “Ferruccio Tagliavini” after an overrated operatic tenor of the time. Even through their closed door, you’ll hear the pseudo-Tagliavini tipsily serenading his giggling inamorata with “La donna è mobile” or “’O sole mio.”

Chances are you won’t hear or see Ann Parry — Ann the Irishwoman — who lives in the three-room apartment on the hallway, so I’ll describe her for you. She’s a sprightly, 4-foot, 9-inch 65-year-old whose breasts sag beneath her waist. She and her gentleman friend, Fred, tall and willowy in his off-white seaman’s cap, are relaxing inside, grinning at some sitcom on a rabbit-eared portable TV. They’re smoking unfiltered cigarettes and sipping Ballantines after a long day of fishing at City Island. Their Irish eyes are smiling.

Although the door across from Ann’s apartment is ajar, I wouldn’t recommend peeking in. Marty the Mailman and Gladys are newlywed lovebirds (who actually keep a pair of lovebirds in a standup cage in their kitchen), and it might not be a good time for a visit. I had acquired the habit of wandering into their apartment, and my mother was shocked when, on asking why I was in there so often, I answered, “When their door’s open, I just go inside.”

Far from being disturbed by my intrusions, Marty and Gladys once started hugging and cooing and pecking at one another’s lips, standing in a corner of the kitchen, while I gazed at them as if watching a “grown-up” movie. After a few minutes, I got bored and left. On other occasions, if they weren’t in the kitchen when I walked in, and it was quiet in the apartment, I’d watch the birds for a while and then leave.

It may well be on our floor that you’ll catch our janitor, old bum-legged Mr. Frangipane, hard at work on this sweltering evening, flinging into the dumbwaiter the many greasy brown bags of garbage propped along the wall of the landing. That device will whisk them down to one of his teen boys, who’ll pitch them into the furnace’s gaping mouth like damned souls at the Last Judgment. From there the acrid smoke will rise through the chimney and be wafted to the eyes and nostrils of all the skimpily-clad tenants sitting down to their evening meal with the windows wide open.

If you proceed to the end of the hallway and look through the doorway on the right, you’ll see Mary Pomodoro throwing together supper while spitting out commands to her giraffey daughter Linda (“Finish your homework!”), her bucktoothed son, soon to be known as Vinnie the Firebug (“Get the hell out of the kitchen and go watch TV!”) and to several squealing brats slithering across the linoleum floor (“Shut your traps!”).

We live right across from them in No. 36, the last apartment of all. Our grizzled old bread-man is at our open door in his blue short-sleeved shirt, with his handkerchief fastened around his neck to absorb the sweat of his climb. Three times a week he trudges up to the sixth floor to bring us our round Italian-bakery loaf and collect 35 cents. My mother has just thanked him effusively and tipped him with two shots of Seagram’s Seven to help him cope with it all. He looks delighted.

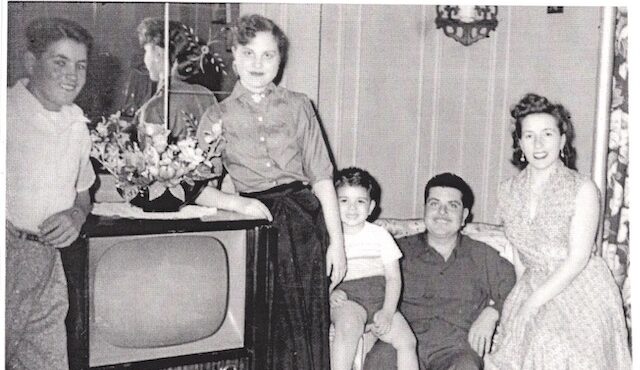

As usual, Mom seems unaffected by the heat, whereas Dad, just home from his grueling job as a construction laborer, has retreated one flight up to the tar roof to breathe some more-or-less fresh air. (It isn’t quite hot enough yet for him to sit on the fire escape outside their bedroom window.) I’m still a few months shy of 8, so I don’t mind the heat and humidity as long as I can sit on the couch and watch the Three Stooges, Superman or Abbott and Costello on our boxy Philco TV while cooling off with a brimming glass of Pepsi.

Our sole little fan is whirring in the kitchen, while Mom bustles from steaming pasta pot to sizzling frying pan and from narrow sink to midget fridge. There’s nary a sound of an air conditioner anywhere in the building.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

The author has brought back many memories to this Bronx-bred boy from the mid-’50’s. These folks he writes about were much more than stereotype New Yorkers. They represented the multi-cultured hard working class and homemakers that comprised the urban American household of the Greatest Generation’s neighborhoods.

When we lived in a fifth-floor, elevator-less apartment then in the South Bronx, my father Tony has to carry my six-year old sister up five flights of stairs daily, due to her rheumatic heart condition. Our neighbors were immigrants from various countries, and always supported one another in various ways. Mr. D’Epiro’s descriptive analysis of a child’s average day is a colorful summary of the black-and-white memories to this aging Bronxite.

Thank you Mr. D’Epiro!