I am reminded every day at work that my memory isn’t what it used to be. When I was a kid, I could remember which baseball card numbers I needed to complete the set of 660 Topps cards. I didn’t need a written list. I guess they would call that a photographic memory. Now, I leave my house without remembering to comb my hair! Or I get in my car and try to start it only to discover that I left my keys on the table! There’s a term for the status of my current memory, but I can’t remember what it is!

The point is that memory, over the time of one’s life, accumulates more content, but as one gets older, the ability to retrieve those memories is much more difficult.

So what does this mean to the genealogist? It should mean a lot!

If you are like me and you are your family’s central connection to their history, you end up with a lot of tidbits of information going through your head and it is very hard to stay focused on a particular area of research.

Those of us who have spent decades accumulating a large family history need to spend more time on several areas so the memory of what we have done doesn’t fade away.

I was at Mount Carmel cemetery not long ago and I found the grave of a brother of my great-grandfather. Paolo was his name. He was born in Italy in 1895 and died of tuberculosis in Chicago in 1915. There is a marvelous porcelain photo of him on his monument. The monument itself is very hard to read, but luckily the photo has survived. It is the only photo of him. No one else has one. I snapped a few photos with my trusty cell phone. A lot of the photos on the old graves at Mount Carmel, and indeed at many other older Chicago cemeteries, have been damaged by lawn mowers, vandalism, neglect and age.

So I looked at the photo of Paolo and I had this thought: This man has been dead for over 100 years. Every single human being who ever met this man during his life is also deceased. I have no way to know what kind of a guy he was. Was he generous? Bitter? Loving? Alcoholic? Helpful? I can’t ask him, and I can’t ask anyone else, either.

When someone is famous, such as Rudolph Valentino, one can consult biographies written many years ago, where the author may have interviewed people who knew and worked with him, or worked with written sources from his short lifetime. So even though Valentino has been gone for nearly a century, we can put together a mental picture of what kind of person he was, at least to those who recorded their thoughts about him. As with my great-grand-uncle, there might not be a single living person who knew Rudolph Valentino personally who could be interviewed today.

So my non-famous relative has no books written about him and there are no interviews with his relatives who could tell us in 2022 what this young man was like, good or bad.

This is the role you, as family historian, need to fill. You need to record, preserve, and disseminate the memories of members of your family.

“Why you?” Because you already have more information about your family than anyone else, and you’ll most certainly need that information as background before you sit down to interview the people who knew the deceased. I can’t be an expert on the process of interviewing, but I can say that the ones who get paid a lot of money on television for interviewing celebrities, they all pour months of research into their subject. By the time we see Barbara Walters interview Katherine Hepburn, Walters knows every event in the Hepburn timeline and can reference that basic information as she probes deeper, to learn more.

So when you want to interview a relative, formally with written questions, or just having a conversation at the dinner table, you already have all that in your back pocket. A total stranger would have to ask all the basics, where were you born, when did your father die, etc. By the time they get to the meatier questions, everyone is tired!

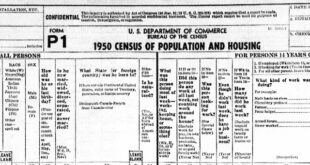

I’m not suggesting you write a 400-page book on your “Paolo” but I do suggest you gather what you can find about him. Paolo left a paper trail. His parents went to the mayor’s office in Italy to report that Paolo had been born. It turns out he was born in his grandmother’s house, and she had been a midwife. It also turns out that he had an older brother, also named Paolo, who was born a couple of years earlier, and only lived a few months. Paolo got on a ship in steerage and traveled to New York in 1912. He was 17, and had he stayed in Italy, he would have been conscripted in the army at age 18. So he was making the difficult decision to leave, presumably never to return. Had he gone back, he could have been conscripted right then and there. Then in 1915, it was reported to the Cook County office that Paolo had died of a disease that claimed about 1/7th of all the people who ever lived on Planet Earth: tuberculosis (aka consumption). The death certificate says he had the disease for over a year. Yet he died at home. Many people ended up at a sanitorium, which was a hospital specifically for TB sufferers. I presume he and his family could not afford it. The death certificate said he was buried in Proviso Township, which is what they probably said before there was a “Hillside.”

The cemetery has the final pieces of his paper trail. It has a burial card that has his name, the date of his burial, and the section, block and lot numbers. That card does not mention that there was a monument on that lot. Many thousands of people just like Paolo lie buried in the same cemetery, but with no marker at all, and certainly with no photo.

The cemetery also has a daily burial log, that shows the nine other people who were buried there on the very same day. Nine other families who mourned nine other people. The later pages of this burial log go into late 1918 and we see, on a similar day, 50 families mourning 50 other people who died in the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Sadly, Paolo left us with little else. He did not live long enough to register for the U.S. Army draft for World War I. He did not apply for American citizenship. After only a few years, some of it spent ill, he didn’t have time to accomplish much of anything.

So you can gather your thoughts on this man who you never met, and while it won’t paint a vivid picture of him, you can put some ideas down that can tell a slightly better story than his old cemetery monument.

Next month, I will talk about the family members whose stories can be told by surviving friends and relatives.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian