Anyone who knows me well, knows that I’m a stubborn person. Most people who don’t know me well believe I’m stubborn, too!

Every so often, I write a column to ask you to do something that I’m not that good at, partly to push myself into getting better as a genealogist.

I have been spending a lot of hours going through records I already have, in an attempt to better document my research. Why should we do this? I know where all my copies are. The papers are in piles and in boxes, and the digital images are all named IMG3431.JPG, so everything is ok…..

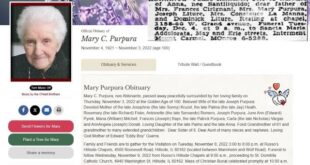

It is an unfortunate fact that one day, we will not be able to continue our research. If we have health issues, or worse, we will not be able to keep researching and we will either pass the project to another relative who will continue the work, or we post our research on Ancestry or Familysearch so others may learn from our hard work, or the project fades away.

It is a tragedy for us to spend years of our lives putting all this together, and when someone else looks at it, they can’t make sense of it, and the documents we acquired to put it together are not with the actual family tree file. So how does a total stranger, or even a close cousin, know that what we found is accurate? In order to create a level of trust in our hard work, we need to document our facts with the resources that we used.

The debate on how to document has been raging for decades. As soon as someone believes they have solved the problem once and for all, someone else decides they are right and the others are wrong. It seems simple to me. What are we trying to do when we document our work? We are showing other people the path to find a copy of the document(s) we used to conclude that a piece of information is correct. After all, we were only physically present for some events that happen in our family tree, and very few at that. For example, we can prove conclusively that we were present at the birth of our child, or we were at the hospital when Nonna passed away, so we can prove what date and in what city these events occurred. But for everything else, we can’t prove anything. We need the various records that are generated at the time of the birth, or marriage, or death, or military enlistment, or from the census taker. “I wasn’t there in 1910 when the family lived on Grand and Ogden, but an eyewitness asked for the names and ages of our family on census day.”

Part of the problem is that we are using copies of original documents, but we rarely are working with the originals themselves. We may have used microfilm copies of original documents, or we may have used a web site to view a digital copy. So if we are trying to tell other researchers where to go to find these documents, do we tell them the web site, or the microfilm number, or the building where the original documents are located, or a combination of all three?

So, WHAT do we document? If you use genealogy software like Family Tree Maker, or you keep your tree on Familysearch.org, they will tell you which pieces of information should be documented. Let’s start with the basics. Do we need to document someone’s name? Yes, we do. “But I know my grandfather’s name…” Did grandpa have the same name all of his life? Could he have been born “Francesco Addante” in 1882, and died as “Frank Dante” in 1953? Which name did he use? What years did he use it? If someone is going to look for records about Francesco/Frank Addante/Dante, which name did he use on his draft registration? On his citizenship papers? On his passenger list?

My family tree maker software asks me to document the name, birth date, birth city, death date, death city, marriage date, marriage city, and basically any other fact I try to enter for each person. “Lived at 1247 W. Grand in 1920”. “Was a Staff Sergeant in World War I from January 1918 to February 1919” “Buried at Mount Carmel Cemetery in Section 14 but was moved to Queen of Heaven Mausoleum in 1962.” All facts, and each one needs some backup.

So we see that we have multiple possible names and multiple possible sources. On top of that, we may have more than one Frank Dante in Chicago. So when we look for documents, we need to be sure it’s OUR Frank, by checking other information on the document. Once we are convinced this is our Frank and not that other Frank on the South Side, we need to tell anyone else who is looking for the same person that we’ve done our homework.

So in your genealogy software, or your on-line tree, you need to post the person’s name, and as many “a-k-a”s as you can find. There is a fine art to knowing the difference between a second spelling of someone’s name, and a badly misspelled version. For example, the census taker might spell Francesco Addante as Frencisca Adanti. It’s close, but Frank never used this spelling in his lifetime. For the vast majority of people in our family tree, we may not know which name or spelling they actually used. All we know is that each document seems to have a different spelling. So in order to make it easier for others to find the same document, it is important to record in your source the spelling of the name that was used to find it.

If you searched familysearch.org for Frank and the web site showed you “Frencisca Addonta”, your source is going to be “familysearch.org Index to Collection ‘World War I Draft Registration cards’ using the name “Frencisca Addonta”, Retrieved 17 July 2019” It looks complicated, but anyone who is looking for that draft card now knows exactly the spelling to use to retrieve that document.

Just as important is the document number in that collection. Familysearch has these collections catalogued, with individual film numbers to break down the collection into smaller pieces. Some film numbers date back to the physical microfilm days, and some are digital “film” numbers. Each film has between 100 and 5000 images. Each image may have a document number that was used by the city or Cook County or Triggiano Italy to find that document in their paper collections, before there were microfilms.

So it is one thing to find Frencisca Addonta, but it is just as important to reference the film number, the image number, and the document number. So, in your source, you should reference the Familysearch collection, film number, image number, document number, the name “Frencisca Addonta” and the fact that you retrieved the document from the internet. If you are at the archives and familysearch is not involved, then you need to cite your source by where you found the record, whose office controls access to that record, and the document number. “Cook County Archives, Chicago, IL, Clerk of the Circuit Court, Divorce Records microform KV915, case #1938-13245” In this example, they have their own numbering system, they call it microFORM not microfilm, and you physically had to go there to get a copy of the record. The name is not mentioned because you didn’t find it on-line. Anyone who looks at that record may interpret the spelling differently, so you don’t want to tell someone to find it under the wrong spelling.

This entire process can take a lot of the fun out of genealogy, but unless you document your facts with sources, you’re building a very large project that no one will be able to use.

If you have any questions, send me an e-mail at italianroots@comcast.net and please put “Fra Noi” in the subject line. Have fun!

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian