When starting our research, most of us were eventually given guidance by experienced genealogists. At least I hope we all were. A lot of my earliest work came from interviewing living relatives, because I had to ask them for the names of their brothers and sisters, and then the dates of birth and death. I learned early on that once their sister has been dead for 30 years, it was not on the tip of their tongues what her birthday was, having not celebrated it for so long.

When they listed their siblings for me, they almost never mentioned any children who died very young. Genealogically, they did not produce offspring, but they were important in explaining the life story of their parents. Eliminating the loss of a 3-year-old from their story, while it makes the story more pleasant, also makes it much less complete.

So I quickly learned that I could not always rely on my relatives for the details that make a family tree thorough and complete. I was, and still am, very happy and grateful for all the help they have given me over the decades, but I did need to check out their details through the use of vital records.

Another thing I learned early on, and a theme I have hammered home in this column many times, is to seek out vital records written as close to the event in question as possible What does this mean? Typically, a birth certificate would be written and filed within a few days or weeks of the birth of a baby, so you should be able to trust that the date of that birth is pretty accurate. Sometimes the birth date listed on a birth certificate is off by a day or two because the midwife who assisted in the birth also assisted in twenty other births in the past couple of weeks, and could get a little confused.

Another thing I learned early on, and a theme I have hammered home in this column many times, is to seek out vital records written as close to the event in question as possible What does this mean? Typically, a birth certificate would be written and filed within a few days or weeks of the birth of a baby, so you should be able to trust that the date of that birth is pretty accurate. Sometimes the birth date listed on a birth certificate is off by a day or two because the midwife who assisted in the birth also assisted in twenty other births in the past couple of weeks, and could get a little confused.

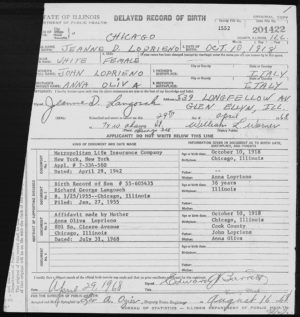

One other way a birth certificate could be inaccurate is that it is a “Delayed” birth certificate. This is a document filed years or decades after the birth by someone whose parents failed to file a birth certificate at the time of the birth. As recently as 1915, birth certificates were not required in Cook County, and even after 1916, some immigrant families did not know the law and did not file either. Some original birth certificates have no given name on them, and years later, a delayed birth certificate would be submitted to get the name on it, and clear up any other inaccuracies such as the parents’ names or ages.

Now you could tell me that the birth date can be found on the death certificate as well. This is usually true. It is also the least accurate place to look for a birth date, because the death occurred (hopefully) many years after the birth, and people’s memories (like my relatives, or even mine) can get foggy. When you enter a birth date in your tree, record your source. The source could be “Zi Zi Rena interview 1986” or “Death certificate 1954” or “Birth certificate from Potenza, 1883”. You can tell from looking at the source that the most accurate would be Potenza, and second place would be a toss-up between the death certificate and Zi Zi Rena.

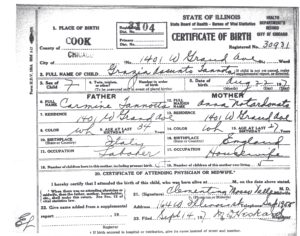

Let’s focus on Chicago and Cook County birth certificates today, and let’s see what type of data is available on them. There are very few births available from the 1870s after the fire, and hardly any from before the fire. Most birth certificates for people born in Chicago before 1871 were filed after the fire, which made them the first “Delayed” birth certificates.

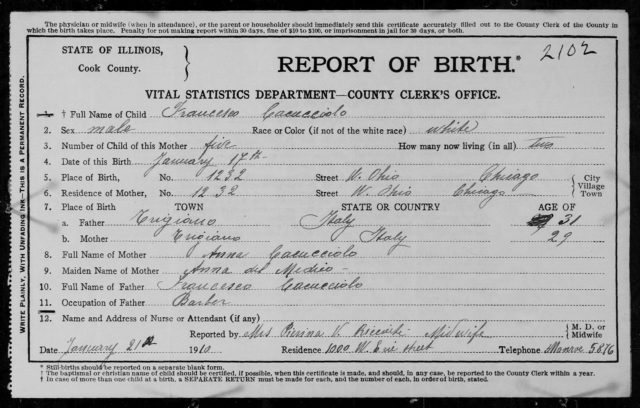

The 1870s asked for the most basic data one would expect from a birth certificate: Name, Sex, Race/Color, Number of child of this mother, date and place of birth, residence of the mother if the birth was not at home, father and mother’s name, age, nationality and place of birth, and the father’s occupation. Moms must have all been stay-at-home at the time! Then there is a date of the certificate, names of the people who attended the birth and the doctor or midwife who ran the show, as it were.

The 1870s asked for the most basic data one would expect from a birth certificate: Name, Sex, Race/Color, Number of child of this mother, date and place of birth, residence of the mother if the birth was not at home, father and mother’s name, age, nationality and place of birth, and the father’s occupation. Moms must have all been stay-at-home at the time! Then there is a date of the certificate, names of the people who attended the birth and the doctor or midwife who ran the show, as it were.

Let’s talk about a few of these. The “number of child of this mother” can be very handy in determining that there might be other missing children who you have not found yet, especially ones who died young. The nationality can say “Italian” and the father or mother could be born in Chicago, which is why the nationality and place of birth are separate entries. Around 1910 they eliminated the nationality and simply asked the birth city and country.

The same form was used from 1878 through 1915, and finally they changed the format, which lasted at least past 1940. New information found on this format is “Twins, Triplets or other?” and “Number in order of birth” which was meant only for multiple births. In the 1916 format, the mother finally had an occupation, along with dad. They also now asked “number of children born to this mother” and “number of children of this mother now living”. This is an important clue to figure out if a child died and you don’t know about it. In the 1920s, a question was added “what treatment was given the child’s eyes at birth”. A lot of them say “silver nitrate” but there are other answers. I’ll admit to not having the medical background to know why this was important to list on the birth certificate back then.

In future columns we will discuss the data available from marriage licenses and death certificates.

Write to Dan at italianroots@comcast.net with any questions.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

During the 19th century in Italy, it was not rare that babies born in the latter part of the year had their birth registered on January 1st of the following year. My aunt was born in November, but her Italian birth certificate said January 1st. This was especially true for male births in order that they be placed in the next “class” or year for army draft purposes. As you mention, it depended when the husband or midwife, etc got around to the municipality to register the birth. My father was born on Feb. 18th but his birth certificate states Feb.20th, when his father finally thought about going to the

City Hall.