Let’s discuss how this all works. Most records are hand-written. Problem number one. So for them to be indexed on-line, someone has to read them and type them in. This, of course, is called “indexing.” I know they are working on computer technology to try to read handwriting and convert it into computer text, but let’s presume that such technology is a long way from perfection, especially when reading handwriting from a century or two ago.

So who is indexing the billions of records so we can search them so easily? We could probably end all unemployment if people could be paid to index records, but then your genealogy web sites would be prohibitively expensive to pay for all that labor. What this means is that the people doing the indexing are almost always unpaid volunteers.

There is nothing wrong with volunteer indexing. The fact that people give of their free time is a wonderful thing. However, the results are not always the best, and this really isn’t a reflection on the volunteers or their experience. Frankly, who would index genealogy records unless they are involved in genealogy research, especially if they’re not paid for their time? So we can assume that most indexing volunteers have enough connection to genealogy research, that they know how important it is to be as accurate as possible.

So if the volunteers care about their work, why is so much of it so inaccurate? There are many reasons. There are people out there who index any records that are available to work on. We call them “power-indexers” and I am not among them, but I’m darn glad they’re out there! They have the time and discipline to spend an hour every day just indexing records. But it is not always easy to find a “project” to index records from a town or language one is very familiar with. So the power-indexer will grab any old records that are queued up ready to be indexed. The only problem is that the power-indexer may not know anything about the town they are indexing. Also, the person writing the records in the town may have very different handwriting than another person who wrote records for the very same town.

One other important aspect of volunteer indexing is that they ask two different indexers to index the very same records. The system is that if both indexers see the same thing in the handwriting, then it is a double-check against one person who may read it incorrectly. Sad to say, frequently two people read the same handwriting and come up with the same incorrect result.

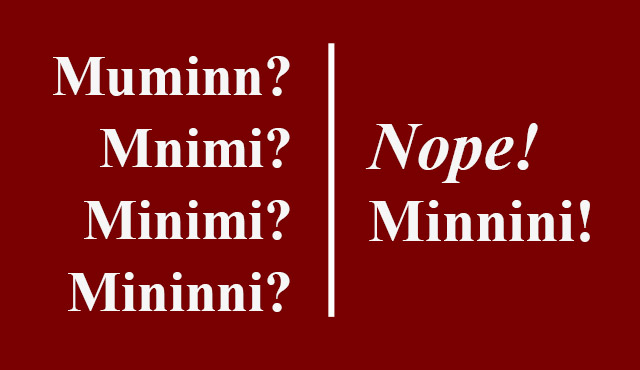

When working with Italian records in particular, the same surnames keep popping up because people did not move from town to town very often. So it would seem to be important that people should be familiar with the town they are indexing, so they can guess correctly what the spelling should be. I have a surname in Triggiano which is “Mininni”. A handwritten version of “Mininni” is probably ok with the upper-case “M” at the beginning, but the rest of the handwritten name is a mess.

When someone hand-writes the lower-case “i” and the lower case “n”s the pen goes up and down repeatedly. None of these letters has a rounded component. The lower-case “b”, “d”, “o”, “a”, “p”, “g” and “c” all have a part of the letter wider than the up-and-down motion to write “t”,”u”,”i”,””f”,”l”,”v”, and especially “n” and “m”. The up-and-down-strokes of the pen run together and look like one great big scribble. Plus the dots on the page are not always dots. They could be phantom dots on the page from the age of the page, or dots on the computer image, so you can’t always tell where the dot is in order to tell and “i” from an “n”. Or the dot may be hard to see, so you can’t be sure if there is an “i” in the name or not, and that will definitely make the indexed result incorrect.

A researcher such as myself who is familiar with the surnames of Triggiano would easily know that the “M” with the scribbles is “Mininni”. An indexer probably is looking for consonants and vowels in the right order, for an Italian surname. If these were Polish or Russian records, there might be a lot more consonants together in a surname, but Italian names are usually a consonant or two, then a vowel, then another consonant or two etc. So if you see an “M” and a squiggle, and you need to figure out a name, how would you do it? Well, there are not many consonants that could follow an “M” in Italy. In Ireland, or Scotland, you might have “Mc”. In Poland or other Slavic countries, you might have “Mr” or “My” or “Ml”. But in the Motherland, the “M” should be followed by a vowel. Fortunately, “a”, “e” and “o” are wider than a regular letter and would be hard to be handwritten with straight up and down. That leaves “I” and “u”. The “u” in particular looks too much like the “n” and they run together. If you can’t see the dot, you might presume it is not an “i” which only leaves “u”. And if you don’t know anything about Italian surnames, you might conclude that the name starts with two or three consonants in a row. (It might have different consonant combinations in the far north, where the names might have a German or Swiss origin.)

I’m not trying to make you into handwriting experts with all this technical analysis. For one thing, I am not such an expert. All I have is a lot of credits at the School of Genealogy Hard Knocks! The point is to explain why some indexed names are so completely wrong, and your search will never find Mininni when the two indexers both saw “Muminn” or “Mnimi”. Most genealogy web sites will not find your search if the indexed record is so far off.

Next month, I will teach some work-arounds to help you find these hard-to-find records.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian