Similar in spelling but different in meaning, false cognates can be sources of embarrassment and laughter when unleashed.

As I work on making travel reservations for a coming trip to Italy, I’m reminded of a verbal blunder I once made while corresponding with the proprietor of a bed and breakfast. After agreeing on the dates and cost, I asked how I could send the deposit. I didn’t know the word for deposit and didn’t want to take the time to look it up, so I just called it the deposito, because I was pretty sure I had heard that word before in my travels.

True, I had heard the word, but it is not used the same way in Italy. It means warehouse or storeroom. The word I needed was quite different, which I soon discovered when the proprietor wrote back with instructions on how to make the caparra, with no mention of my gaffe. Probably he had heard it from other foreigners before.

Such words are called false cognates in English and falsi amici (false friends) in Italian because they fool you into thinking you know what they mean, but they actually mean something else. Here are just a few other examples of false Italian friends:

Sensibile means sensitive, not sensible

Fame means hunger, not fame

Largo means wide, not large

Fattoria means farm, not factory

Noioso means boring, not noisy

Parenti means relatives, not parents

Preservativi means condoms, not food preservatives

Many, many times the Italian and English words truly are similar, which makes Italian easier to learn than other languages, but one can’t take anything for granted. I have seen and heard some funny stories about false friends and other language blunders that are worth relating.

Of course, the problems go both ways. I once saw a sign in Italian about how a museum was being remodeled and thus was temporarily closed. The explanation ended with “Ci dispiace per il disagio.” Agio means ease or leisure, and disagio means inconvenience, which could be translated more literally to mean a lack of ease. The sign included a complete translation below into English, and it ended with “We apologize for the disease.”

Almost every English speaker learning Italian can provide ready examples of awkward misstatements they’ve made. Dianne Hales, author of “La Bella Lingua,” recounts: “I’ve learned a lot of Italian from slips of the tongue. Once we were on a boat sailing to Sardinia, and my husband and I invited the two co-captains to join us for dinner in port. They worried about interfering with a romantic dinner, but I assured them that after so many years of marriage I feared my husband was getting bored. Except I said boring. It made for an interesting three days at sea!”

My wife once wanted to tell our hostess how much she had enjoyed a remarkable home-cooked dinner. Lucy hoped to say, “You are amazing” in Italian, and the first two words proved to be no problem — but not the word amazing. It turns out there is no exact equivalent in Italian. Still Lucy had heard something that sounded like it, so she went ahead and said, “Tu sei ammazzata!” When the host looked confused, I quickly chimed in, “Vuol dire, tu sei fantastica.” That is, “She wants to say you are fantastic.” Ammazzare means to kill, so what Lucy had actually told the hostess is “You are killed.”

Delia Simeone, who plans to obtain her Italian citizenship and move from Australia to Italy in the future, said she is “quite proficient at butchering Italian.” She once referred to her home as casino instead of casina (little house). Unfortunately, casino is slang for a house of prostitution, and her Italian friends still tease her about that.

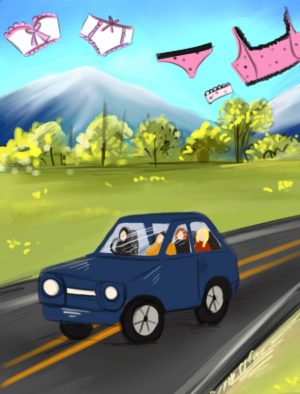

Italian American Connie Rozzo Nickell tells the story of a cousin, 12 years old at the time, who tried to impress her aunt who was visiting from Sicily. “They were traveling through the mountains in Pennsylvania,” Nickell said, “and my cousin thought she said, ‘Look at the beautiful mountains!’ But instead of montagne, she said mutandine (underwear). The aunt looked surprised, and everyone else started laughing. My cousin loves telling the story now that she’s an adult.”

Most mistakes are quickly forgotten because they are spoken, not written, and then only a few people hear them. Sometimes the mistakes are more public and permanent, however. When General Electric merged with French company Plessy Telecommunications in 1988, GE decided to call the new partnership GPT — but without consulting the French-speaking partners. GPT sounds very close to the phrase “J’ai pété,” which means, “I passed gas.” The name change lasted less than a year but is still remembered in France.

An entire article could also be written about the many, many words in Italy that have ordinary meanings but also are earthy sexual innuendos. For example, scopare means “to sweep,” but it’s also crude slang for “to have sex.” But we’ll leave the numerous other examples of this genre for some other day — or even better, some other author.

My favorite story comes from my friends Steve and Patti Gray. It involves a British missionary lady who was ordering some work done on her kitchen while she returned on leave to England. She had laid out the plans just fine, until she told the Italian carpenters that she wanted them to purchase and install a cabinet, which she referred to as a cabineto, right here. “Qui?” they asked incredulously. “You want it here? But why?”

“Because that’s where I want it,” she said. “It’s the most convenient place.”

They continued to question her, but she was insistent: “Mettete il cabineto qui.”

And so they did. There is no cabineto in Italian, but there is one that sounds very much like it, so they did what they thought she wanted. When she returned, she found a gabinetto, a toilet, installed in her kitchen.

MORE FALSE FRIENDS

Attualmente (currently), NOT Actually (in realtà)

Camera (room), NOT Camera (la macchina fotografica)

Cocomero (watermelon), NOT Cucumber (cetriolo)

Comprensivo (understanding), NOT Comprehensive (completo)

Confetti (candied almond), NOT Confetti (coriandoli)

Crudo (raw), NOT Crude (volgare)

Educato (polite), NOT Educated (istruito or colto)

Educazione (good manners), NOT Education (istruzione)

Eventuale (any), NOT Eventual (finale)

Fabbrica (factory), NOT Fabric (tessuto)

Fastidio (annoying), NOT Fastidious (pignolo)

Gentile (nice), NOT Gentle (dolce or leggero)

Libreria (bookstore), NOT Library (biblioteca)

Magazzino (warehouse), NOT Magazine (rivista)

Morbido (soft), NOT Morbid (morboso)

Patente (license), NOT Patent (richiesta di brevetto)

Peperoni (sweet peppers), NOT Pepperoni, the spicy sausage (salame piccante)

Pretendere (to expect), NOT To pretend (fare finta)

Rumore (sound), NOT Rumor (voce)

Simpatico (nice), NOT Sympathetic (comprensivo)

Stravagante (eccentric), NOT Extravagant (sprecone)

Illustrations by Banashree Das

The above appears in the August 2019 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian