Columbus’ detractors would have us believe that he was a genocidal slave trader who tyrannized natives and settlers alike and stopped at nothing to turn a profit and subjugate the islands. If you read the source material closely, though, all that dissolves into inaccuracy.

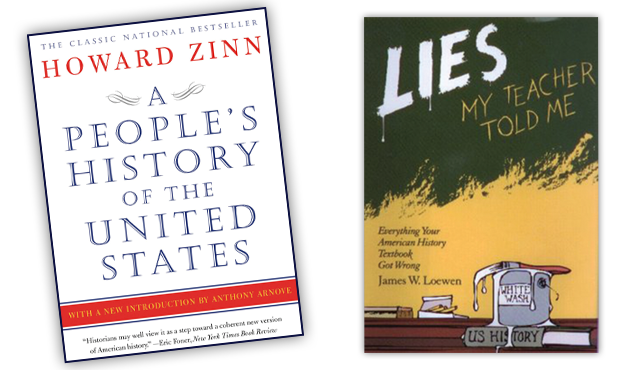

The worst offenders were Howard Zinn, author of “A People’s History of the United States,” and James W. Loewen, who penned “Lies My Teacher Told Me.” Playing fast and loose with the truth at almost every turn, they offered no real proof for many of their assertions, often serving up quotes that were taken wildly out of context.

Amplified exponentially by the internet in recent decades, their two slim chapters morphed into a tidal wave of misinformation that has swept through every level of American society.

Surprisingly, some of their misconceptions are rooted in the work of noted Columbus scholar Samuel Eliot Morison. An exhaustive researcher, Morison’s analysis of Columbus’ tenure as governor was uncharacteristically shoddy on a couple of key points.

Often, the truth of the matter can easily be unearthed simply by looking at the entire passage in which a seemingly damning snippet is nestled. On occasion, you need to get a grip on a much bigger picture, or check the validity of one account against others.

An unlikely ally in this effort is Bartolomé de las Casas, a colonist-turned-friar who arrived on the scene shortly after Columbus departed. Las Casas’ knowledge of Columbus’ actions was encyclopedic, and though he admired Columbus as a person, he often wrote scathingly about his practices.

Modern opponents of Columbus quote him liberally — and not always faithfully — when they want to bolster their points, but they manage to completely overlook the many times his writings contradict their assertions.

With the previous article in mind, let’s focus on the most outlandish of these assertions and see how they fare when exposed to the bright light of reality.

Columbus meant to subjugate the natives from the start.

To assist in his research, Morison wrote the definitive translation of the journals Columbus kept during his first voyage. The originals were lost to time, so Morison worked from a transcription by las Casas, who summarized or quoted as he saw fit.

Even in its condensed form, the surviving document contains thousands upon thousands of words, 99 percent of which speak to Columbus’ benevolent intent. For some unaccountable reason, Morison overlooked all of that, choosing to zero in on a half dozen passages that hint at a darker purpose — but only if you look at them sideways. Here are a few of them.

After Columbus met the Tainos face to face on Oct. 13, 1492, he wrote a long entry in his journal that contains the following fateful words: “They ought to be good servants and of good skill, for I see that they repeat very quickly whatever was said to them.”

Here’s Morison’s takeaway, as recorded in his footnotes: “The thought of enslaving the Indians evidently crossed the admiral’s mind at his first encounter.”

If you scroll up the passage, though, you’ll see that Columbus was actually explaining why the cannibalistic Caribs might want to enslave the peaceful Tainos before consuming them.

“They bear no arms, nor know thereof; for I showed them swords and they grasped them by the blade and cut themselves through ignorance. They have no iron. Their darts are a kind of rod without iron, and some have at the end a fish’s tooth and others, other things. I saw some who had marks of wounds on their bodies, and made signs to ask what it was, and they showed me that people of other islands which are near came there and wished to capture them, and they defended themselves. And I believed and now believe that people do come here from the mainland to take them as slaves. They ought to be good servants and of good skill, for I see that they repeat very quickly whatever was said to them.”

Bear in mind that Columbus was adamantly opposed to that sort of treatment. Paraphrasing from his journals, las Casas wrote: “The Admiral in all regions ordered all his people to take care not to annoy anyone in anything and to take nothing from them against their will, and so they paid them for all they received.”

Morison offers the following snippets from an encounter with a different Taino tribe the next day as further evidence of Columbus’ dark intent: “These people are very unskilled in arms … with 50 men they could all be subjected and made to do all that one wished.”

A fuller reading reveals that Columbus was ruling out the need to build a fort, presumably in case they encountered hostility, while trying to divine the crown’s intent.

“I kept going this morning, that I might give an account of all to Your Highnesses, and also (to see) where there might be a fortress; and I saw a piece of land which was formed like an island, although it isn’t one (and on it there are six houses) the which could in two days be made an island, although I don’t see that it would be necessary, because these people are very unskilled in arms, as Your Highnesses will see from the seven that I caused to be taken to carry them off to learn our language and return; unless Your Highnesses should order them all to be taken to Castile or held captive in the same island, for with 50 men they could all be subjected and made to do all that one wished.”

Everything Columbus did and wrote during his first stay militated against such an approach, but that wasn’t his call. The matter was settled when the queen instructed Columbus to treat the natives “well and lovingly” as he prepared to embark on his second voyage.

Morison’s misinterpretation of the above two snippets was picked up by Zinn and Lowen and has echoed through the decades since. Here’s another that didn’t gain as much traction.

In response to this snippet — “Nothing was lacking but to know the language and to give them orders, because every order that was given to them they would obey without opposition.” — Morison wrote, “Every man in the fleet from servant boy to Admiral was convinced that no Christian need do a hand’s turn of work in the Indies; and before them opened the delightful vision of growing rich by exploiting labor of docile natives.”

This was already an inane contention given Columbus’ commitment to the exact opposite, but it utterly evaporates when you glance upward in the journal.

“The Admiral gave them glass beads, brass rings and hawk’s bells, not that they demanded anything, but it seemed to him right; and more over says the Admiral, because he already considered them Christians, and for the Sovereigns, more than the people of Castile. And he says that nothing was lacking but to know the language and to give them orders because every order that was given to them they obey without opposition.”

Columbus was actually commenting on the likelihood of the natives converting to Christianity without coercion. Remember that Columbus was intent on bring the native to the faith through love, not force — and that all monarchs — European and native alike — expected unquestioning obedience.

(To prevent this article from going on forever, I’m going to switch gears here and summarize rather than address each issue chapter and verse.)

In a letter to the queen on his way back to Spain after his first stay, Columbus wrote glowingly of the treasures to be found in the Caribbean. Snopes, the website dedicated to separating fact from fiction, plucked this bit from the end of the letter as additional evidence that Columbus was bent on enslaving the natives from the start: “Their Highnesses may see that I shall give them as much gold as they may need … and slaves as many as they shall order to be shipped.”

The writer overlooks the fact that Columbus was referring only to the Caribs, who he had promised the Tainos he would vanquish, either in chains or by the sword.

Columbus exaggerated the riches of the Caribbean to convince the king and queen to fund his expedition.

Nonsense, las Casas wrote: “And what can one say about the abundance of temporal wealth in gold, silver, pearls and precious stones? To give an idea, Indian gold is what prevails on the market all over the world.”

Columbus was lulling the natives into a false sense of security during the first stay, departing on his second voyage with enslavement at the top of his to-do list.

Parroting Zinn and Loewen, anti-Columbus agitator Michael Coard wrote the following about the armada Columbus led on his second journey westward. “And during that 1493 voyage, he brought a fleet of 17 ships with 1,200 men for his malicious purpose of enslaving Red/Brown people and robbing them of their land and resources.”

According to las Casas, the expedition was as large and well manned as it was to deter a possible maritime assault by Portugal, which envied Spain’s foothold in the Caribbean. With those resources at his disposal, Columbus could easily have annihilated or enslaved the entire native population. Instead, he sent most of the men and ships home and built an entire settlement without once resorting to forced labor. Meanwhile, he continued to treat the new tribes he encountered during the first several months of his second stay with the same deference and respect that characterized his first stay.

Before returning to his settlement, Columbus toured the islands, taking innocent natives captive in an early slave roundup.

Columbus was actually raiding Carib strongholds, freeing dozens of Tainos from their clutches and keeping a promise to his allies to drag their enemies away in chains. In case you’re wondering how bad the Caribs were, this description of a home that Columbus’ men entered during the raids gives some indication. It comes from the writing of Peter Martyr, one of Columbus’ more even-handed contemporary chroniclers.

“Birds were boiling in their pots, also geese mixed with bits of human flesh, while other parts of human bodies were fixed on spits, ready for roasting. Upon searching another house the Spaniards found arm and leg bones, which the cannibals carefully preserve for pointing their arrows; for they have no iron. All other bones, after the flesh is eaten, they throw aside. The Spaniards discovered the recently decapitated head of a young man still wet with blood.”

Columbus permitted a friend (in some versions, a lieutenant) to rape a native woman.

The rape never happened. One can say that with some certainty after reading all the reports related to the incident. And the native wasn’t just a woman; she was a fierce Carib chief who had a castrated Taino boy with her when Columbus’ men ran her boatload of warriors down.

The only account in which the sexual assault occurred came from the pen of the supposed rapist, a bon vivant and friend of Columbus named Michele de Cuneo who accompanied him on part of his second voyage. According to de Cuneo, Columbus sent him out with armed members of his crew to capture the chief and her men, giving de Cuneo the ringleader as a servant for personally bringing her in.

There is no way that Columbus would have sent a pal and party boy on a mission that dangerous. Moreover, none of the several witnesses to and chroniclers of the capture reported on de Cuneo’s involvement, and they surely would have, given how odd it would have been.

No capture, no prize, no rape. The noisy assault that de Cuneo describes would certainly have come to the attention of others on board and eventually to las Casas, but it appears nowhere in his chronicles.

Because there was no gold, Columbus engaged in a massive slave roundup to generate funds.

First, regarding the gold: 1) There was plenty of it, but it was hard to access for a variety of reasons, 2) Columbus was under no pressure by the king and queen to produce quick results and 3) his stay until that point was consumed with building a settlement, exploring the other islands and dealing with a crisis with the natives that had spiraled out of control.

In the midst of all that, according to de Cuneo, Columbus sent armed men into the forest to gather 1,500 native men, women and children, shipping 500 of them to Spain in chains, doling out another 500 to his men as slaves and sending the remainder fleeing in terror across the island.

Despite de Cuneo’s dubious reliability, it can safely be said that the roundup itself occurred because several chroniclers confirmed it. None of them, however, suggested profit as a motive. Both Martyr and las Casas depict it as a military maneuver aimed at heading off an all-out assault by the natives. Las Casas even identifies the tribes targeted by Columbus as those involved in the bloody response to the abuses the settlers committed while he was off exploring.

Regarding the number and disposition of the captives: If 500 natives were given to the settlers as slaves, it was done without Columbus’ permission, and he put an end to it as soon as he found out about it. Otherwise, las Casas would have caught wind of it and screamed bloody murder.

When slave trading proved impractical because so many natives died in captivity, Columbus instituted an inhumane system of tribute in which natives across the island were required to deliver an unrealistic amount of gold every three months or face the amputation of a hand.

The second slave roundup was a military tactic aimed at averting widespread bloodshed, not a fundraising scheme. When the tactic failed and Columbus won the ensuing war with the natives, he exacted tribute from the tribes that were aligned against him.

Columbus required gold only from those who had access to it, and he halved the requirement when it proved excessive. Las Casas considered the system itself unfair, but deemed the punishment for those who didn’t meet their quotas “moderate.” The severing of hands that modern critics ballyhoo didn’t occur until well after Columbus was removed from governorship.

When the tribute system broke down, to generate revenue, Columbus instituted encomiendas, in which tracts of land and the natives living on them were given as property to colonists.

The Spanish instituted this system after Columbus’ tenure as governor. A precursor of the system was forced upon Columbus by the insurrectionists during his third stay, just as the system was forced upon the natives down the road. He eliminated the tribute system in exchange for cooperation from chiefs who were affected, and he did everything in his power to shield them from the effects of it.

Columbus provided young girls as sex slaves to his men.

That falsehood has its origins in the following quote: “A hundred castellanoes are as easily obtained for a woman as for a farm, and it is very general and there are plenty of dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to ten are now in demand.” It appears in a letter that Columbus wrote to a friend of the queen while he was being shipped to Spain in chains to stand trial. Much of the letter was devoted to condemning the misdeeds committed by the insurrectionists, including that particularly heinous one.

Columbus abused his own men.

Columbus ran a tight ship, even on land, and especially when resources were scarce, winning himself few friends among the men who served beneath him. He was particularly brutal with the insurrectionists as he tried to gain control of the island during his third stay, though las Casas characterized his measures as warranted under the circumstances.

But ordering a man hanged for stealing bread or having a woman stripped, placed on the back of a donkey and whipped for claiming to be pregnant? If the accusation is outlandish, count on it coming from the “testimonies” collected by Francisco de Bobadilla. He was the monster who sent Columbus to Spain in chains, succeeded him as governor and allowed his men to systematically abuse the natives until he was replaced by someone even more monstrous.

Columbus engaged in genocide and other high crimes against the natives.

Critics have long tried to blame Columbus for the gross abuses that took place during and after his tenure, but every single one of the acts they point to was carried out against his expressed commands and/or outside of his control. The previous article contains countless examples.

The worst of those misdeeds are splattered across the pages of Zinn’s book in an ellipses-riddled gorefest that includes stabbings, beheadings, mutilation, rapes, forced labor and wonton destruction that led to suicide, infanticide, starvation and widespread death.

In the middle of all that, Zinn slyly plunks a quote by las Casas that gives the impression Columbus turned a blind eye to those abuses. But all of them were committed either by the insurrectionists during Columbus’ third stay or by his successors after he was removed as governor.

Columbus paved the way for the calamities that followed.

While many modern detractors falsely attribute to Columbus the crimes perpetrated by his successors, more respectable historians like las Casas and Morison contend that he opened the door to them.

But the measures Columbus took to bring order to an island torn apart by his underlings bear no resemblance to the atrocities committed under the stewardships of Roldán, Bobadilla and Ovando.

It’s absurd to contend that the monsters who later decimated the native population were following Columbus’ lead, as though they were children mindlessly modeling the bad behavior of a parent. It’s much more reasonable to contend that their reign of terror would have commenced on Oct. 12, 1492, had they been in charge from the start.

While Columbus was searching Hispaniola for gold early in his second stay — when he was supposedly intent on enslaving the entire island — he paused before the hut of tribal chief to seek his blessings to pass through his village.

By stark contrast, this is what Spaniards were instructed to read aloud — in Spanish — whenever they first encountered native populations during their conquest of the rest of South and Central America.

“I implore you to recognize the Church as a lady and in the name of the Pope take the King as lord of this land and obey his mandates. If you do not do it, I will enter powerfully against you all. I will make war everywhere and every way I can. I will subject you to the yoke and obedience to the Church and his majesty. I will take your women and children and make them slaves. … The death and injuries you receive from here on will be your own fault and not that of his majesty nor of the gentleman that accompany me.”

However imperfect his stewardship was, Columbus served as a storm wall against the atrocities spawned by this mentality. Ultimately, his legacy should be viewed in that light.

That point is aptly illuminated by the following passage from Washington Irving’s “A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus.”

“His conduct as a discoverer was characterized by the grandeur of his views, and the magnanimity of his spirit. Instead of scouring the newly found countries, like a grasping adventurer eager only for immediate gain, as was too generally the case with contemporary discoverers, he sought to ascertain their soil and productions, their rivers and harbours. He was desirous of colonizing and cultivating them, of conciliating and civilizing the natives, of building cities, introducing the useful arts, subjecting everything to the control of law, order and religion, and thus of founding regular and prosperous empires. In this glorious plan, he was constantly defeated by the dissolute rabble which he was doomed to command; with whom all law was tyranny, and order restraint. They interrupted all useful works by their seditions, provoked the peaceful Indians to hostility, and after they had thus pulled misery and warfare upon their own heads, and overwhelmed Columbus with the ruins of the edifice he was building, they charged him with being the cause of the confusion. Well would it have been for Spain, had her discoverers who followed in the track of Columbus possessed his sound policy and liberal views. What dark pages would have been spared in her colonial history! The new world, in such case, would have been settled by peaceful colonists, and civilized by enlightened legislators, instead of being overrun by desperate adventurers, and desolated by avaricious conquerors.”

Setting aside the antiquated notion that the native populations needed civilizing, that portrait of Columbus is what we should be fighting with all our might to bring to the attention of a misinformed American public.

The above appears in the October 2022 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Mille grazie to Rafael Ortiz, author of “Christopher Columbus The Hero,” for setting me on the path to discovering the real Christopher Columbus, and to Chicago-area attorney Michael A. Benedetto for inspiring me to dig deeper.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian