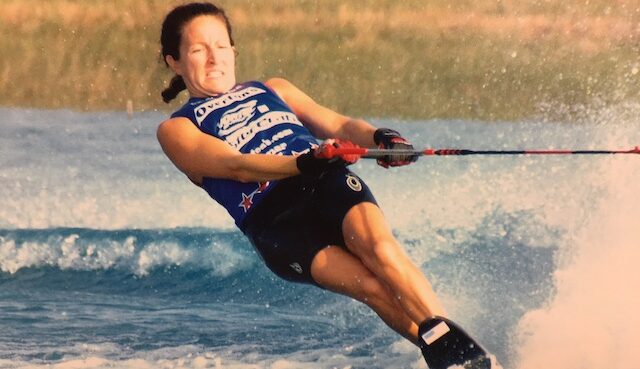

A recreational water skier since grade school, Tina Grossi recently took home gold in ski slalom in the 55- to 59-year-old division of the amateur national championship.

As the top seed in her age division for water ski slalom at the amateur national championships last year, Tina Grossi was the last one on the water, making her acutely aware of how well her competitors had performed.

“Top seed can be both a blessing and a curse. It was a relief when the ski ride was over,” says the 57-year-old Californian, who aced her performance in the women’s 55- to 59-year-old division, earning a gold medal at the 80th Goode U.S. Water Ski National Championships. She boasts two more amateur national gold medals and 14 regional titles in water ski slalom.

Grossi started recreational water skiing at age 7 on summer vacations with her family, who owned a boat. She began tournament water skiing when she joined the team at California State University, Northridge, in her first semester, and she has never looked back.

Tournament water skiing has three events: slalom, trick and jump. In slalom, the winner gets through the course with the fastest speed and the shortest tow rope length.

Slalom skiers are pulled by a boat that runs on a straight line through the center of a course that’s 850 feet long and 75 feet wide. Competitors must go around six turn buoys between the entrance and exit gates. The standard water ski ropes are 75 feet long and are then shortened by increments: the shorter the rope, the more skill it takes.

Under American Water Ski Association regulations, the maximum boat speed for women is 34 miles per hour, but skiers end up traveling faster as they swing their bodies from one side of the course to the other to get around the buoys.

Grossi first entered sanctioned tournaments in 1985 and has qualified for amateur nationals every year she has competed since 1988. In 1998, she qualified for the open division — the pro division — where she competed for 11 nonconsecutive years, earning a fifth-place medal.

One of her proudest moments was in 1998, when she first completed the “35 off,” a 40-foot rope path, during a tournament. “That’s pretty much a goal that any serious slalom skier tries to achieve,” she says.

Slalom water skiing requires balance, coordination and correct technique, as well as focus and the confidence to perform under pressure, she says. “It’s that strong mind, that mental toughness that will allow you to just attack basically, right out of the shoot.”

Grossi has suffered bruised ribs and an especially ill-timed ankle injury in 2004, when she was scheduled to compete in two pro tournaments and the amateur nationals. “That was a real bummer, because I was basically in my prime,” she says.

Grossi, a member of the Canyon Lake Water Ski Club, practices on weekends from May to October, driving 80 miles one way to the closest water ski lake. The vast majority of water ski lakes are private, and access requires owning a home on the property in addition to a boat. Grossi has neither, so she has relied on the support and generosity of friends who have invited her to water ski as their guest over the years. “It’s super expensive to have all these things. I work for a living, so I’m a weekend warrior,” she says, laughing.

During tournaments, boats and drivers are supplied by the organizers. Competitors in the same division get the same driver and boat, whose speed is controlled by GPS, rather than manually as in the old days.

Unfortunately, water skiing is a dying sport, Grossi bemoans.

The reasons are many: the six-digit price tag for boats, the high cost of homeownership on private lakes and the dearth of public lakes with tournament courses. Also, people nowadays prefer wakeboarding and wake surfing, which are physically less demanding. “Between the expenses and the difficulty, we don’t have the younger competitors coming up through the ranks anymore,” she says.

Entering her 39th year as a tournament water skier, Grossi says she deeply appreciates the sport’s healthy lifestyle and the lifelong friendships it has sparked. “As long as it’s physically possible for me, if I’m still having fun, I don’t plan to quit.”

According to Guinness World Records, the oldest female water skier was 90-year-old Edith Murphy of Canada, so there’s still lots of time.

The above appears in the May 2023 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian