Christopher Columbus is a hard guy to get to know. After all, he lived more than 500 years ago, and much of his story has been told by or through others. In the end, everything depends on who’s doing the telling, what they’ve decided to say or leave out, and why.

Much of the debate nowadays is dominated by polar extremes, with vehement detractors embracing an often-false narrative in order to vilify Columbus and passionate apologists frequently downplaying the darker aspects of his legacy to paint a rosier picture.

I found myself in the apologists’ camp early on in my research, but the heat I took from folks who saw things differently served as my wakeup call.

Resolving to see for myself, I dove headfirst into the source material as well as several modern interpretations. When I finally surfaced, one thing was clear: Columbus’ worth has always been in the eye of the beholder.

Many of his own contemporaries brought biases to the table that distorted their accounts, and even quintessential modern Columbus scholar Samuel Eliot Morison overlooked overwhelming evidence to the contrary once he made up his mind that the great explorer was hell-bent on enslaving the natives from the get-go.

As I sifted through these sometimes wildly divergent accounts, a more complex portrait shimmered into view. The Columbus I discovered was a tragic hero who was forced by the misdeeds of others to betray his own lofty plans while nevertheless shielding the native populations from the truly egregious abuses they suffered in his absence and after he had departed.

Another thing I discovered is that you can’t get to know Columbus via sound bites and debate points. You need to view those in the context of his strife-torn eight-year tenure as governor and beyond. So climb on board, and let the quest for the real Columbus begin.

Christopher Columbus earned rightful renown for his prowess as a navigator, and those who knew him considered him to be a man of irreproachable moral character. He was slavishly devoted to Queen Isabella, who took a chance on his risk-fraught proposal to head west in search of the Indies. As a result, he did his best to adhere to her precepts, including her command early on to treat the natives well, give them gifts and protect them from abuse.

Though he was tasked with expanding Spain’s dominion across the ocean, he took a radically different and mind-bogglingly humane approach to conquest from the moment he set foot in the Caribbean on Oct. 12, 1492.

- He gave his men strict orders to treat the natives kindly and refrain from abusing them in any way.

- He respected the natives’ property, insisting that they be traded with fairly and adequately compensated for their efforts.

- While it’s true that one of his main goals was to convert the natives to Christianity, he believed they could and should be brought freely into the fold by love, not force.

- Though he claimed the islands he landed upon for the king and queen of Spain, he considered the natives to be citizens already.

- He envisioned establishing a vast network of trade relations with the natives upon his return.

(For more on the topic of conquest, click here.)

Columbus had a clear-eyed view of the islands’ diverse tribes, praising those who were worthy and condemning those who weren’t. He hailed the Tainos as gentle, generous, intelligent and well governed, and reviled the Caribs, a predatory cluster of tribes that subjected their peace-loving neighbors to cannibalism, rape, castration, torture and slavery in a campaign of systematic depopulation.

He forged a lifelong friendship with Guacanagarí after the powerful Taino king commanded his tribesmen to rescue Columbus’ crew and supplies when the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas Eve. Overcome with gratitude, Columbus vowed that he would put an end to the threat posed by the Caribs, either by enslavement or the sword.

Columbus’ first tour of the Caribbean was an unqualified success. Showering the peaceful tribes with gifts and demonstrations of good intention, he converted wary strangers into adoring allies throughout the Taino tribes. By the time he was ready to depart, he and his men were regarded as gods, with thousands of natives coming from miles around to trade water, food, darts, cotton, parrots and gold for red caps, glass beads, brass rings and tiny falconer’s bells.

To his discredit and contrary to every other action he took during his first voyage, Columbus took two small groups of natives captive: one at the start to serve as guides and the other at the end to bring back to Spain to learn the language and serve as interpreters upon his return. Columbus’ men had to resort to violence only once during their entire stay, wounding a pair of Carib warriors while fending off an assault by a much larger force.

Columbus was so convinced by accounts and evidence of ample deposits of gold on Hispaniola and nearby islands, he set sail for Spain four months earlier than planned. Having lost the largest of his ships, he was forced to leave 39 of his men behind, instructing them to seek gold themselves and barter for it with the natives while he was gone.

On his trip back to Spain, he wrote glowingly of the Tainos and scathingly of the Caribs to the king and queen, promising the monarchs that his next voyage would yield an endless supply of slaves from the ranks of the latter, as well as plentiful gold, spices and other riches.

Following a triumphant reception in Spain, he headed back to the Caribbean with 1,200 men in 17 ships, but with far fewer provisions and supplies than he had requested due to mismanagement by those responsible for loading them up.

On board was a priest whose sole purpose was to study native traditions so he could facilitate their conversion to Christianity. Columbus also carried with him plans to create a system of commerce in which natives were dealt with as trading partners.

The size of the fleet and crew were design to ward off possible aggression by Portugal, which was also intent on colonizing the islands. Most of the ships and men returned to Spain within a few months of their arrival.

Immediately upon his return to the Caribbean, Columbus began to make good on his promise to the Tainos, visiting islands controlled by the Caribs, destroying their boats, taking several of them prisoner and freeing dozens of Tainos that were being held captive.

Triumph dissolved into tragedy, though, when Columbus returned to his settlement on Hispaniola to find that all the men he left behind had been slaughtered at the command of Caonabó, a warlike native king with dozens of lesser chiefs under his control.

With 1,200 well-armed men, Columbus could easily have enslaved or rained death upon the tribes responsible. When he determined that the lethal assault was triggered by abuses committed by his own men while he was away, he moved to another part of the island and built a new settlement.

In Columbus’ absence, his men had turned on each other and several had fled the settlement, taking as much gold as they could carry and seizing native women as consorts along the way. An unquenchable hatred had been engendered between the Spaniards and the offended tribes, which gradually spiraled out of control until it consumed the whole island.

Gold was found in abundance in the early months of Columbus’ second stay, but it was hard to access, and digging for it was put on hold. Heavy rains, diseases and dwindling supplies began to take their toll, but Columbus’ main challenges came from the men themselves.

Many of them were sons of the Spanish gentry, who had no hope of an inheritance and were looking to make a quick fortune in the New World. Faced with the rigors of building a settlement in such adverse conditions, some of them plotted mutiny, and hundreds of them returned to Spain, bearing with them a host of complaints mixed with outright lies.

In one of the many ships that returned to Spain, Columbus sent several Carib men, women and children along with a proposal to extract many more from their tribes, educate and rehabilitate them, and return them to the islands as shining examples of Spanish benevolence. The queen put Columbus’ proposal on hold pending further discussion.

In that same letter, Columbus offered detailed explanations for the lack of immediate gold production, which were met with sympathy and understanding by the monarchs. His request for regular supply runs from Spain were also well received, but they went largely unmet.

As Columbus shed hundreds of men due to illness, death and departures, tensions with the natives continued to rise. Forts replaced mere settlements, and he sent troops marching in formation into the forest on two separate occasions to scare off anticipated attacks by Caonabó and his allies.

During the second excursion, natives from a tribe under Caonabó’s sway pretended to help Columbus’ troops across a river, only to make off with the clothing they were carrying. When their chief refused to return the items, Columbus’ captain took it upon himself to make an example of them.

Without Columbus’ permission, the captain had the ears of one of the thieves cut off, and brought the offending natives and their chief back to the settlement to stand trial. Columbus made a show of threatening to execute them, wringing a promise from the chief and his allies to curtail hostilities.

While this was taking place, members of the chief’s tribe surrounded a group of Columbus’ men who were still in their territory. The natives were preparing to capture or kill them when Columbus’ men were rescued by a fellow Spaniard on horseback.

Despite massive attrition in his workforce and rapidly decaying relations with Caonabó and his allies, Columbus never once pressed a native into service against his or her will, and he continued to treat the new tribes he encountered with deference and respect for their traditions.

Reluctant to leave Hispaniola in such a tumultuous state, Columbus nevertheless heeded the king’s directive to set out in search of the mainland, giving his men strict instructions to maintain peaceful relations with the natives.

His five-month exploration of Cuba and Jamaica was filled with positive encounters with the local tribes. Having abandoned his effort to convince the queen to neutralize the Caribs through enslavement, he was intent on wiping them out upon his return. But the stress of guiding three ships through the treacherous waters of the Caribbean left him practically bedridden, and he abandoned the plan.

In that debilitated state, Columbus returned to find Hispaniola at a tipping point, with egregious abuses by his men leading to violent reprisals by the offended tribes. His dear friend and ally, Chief Guacanagarí, was caught in the crossfire. One of his wives was murdered and another kidnapped by enraged tribal leaders in retribution for his allegiance with Columbus.

To head off the major native offensive that was sure to follow, Columbus had hundreds of noncombatant natives from the retaliating tribes seized and 500 sent to Spain. After a review by theologians, the queen accepted them as a consequence of the strife with the natives and allowed them to be sold into slavery.

Columbus’ attempt to terrify the natives into submission backfired, leading to an uprising by many of the tribes on the island. With countless thousands of native warriors massed and ready to strike, Columbus quelled the assault with a force of about 200 armed men with attack dogs. Many natives who were caught in the crossfire fled to the mountains to escape.

As was customary in both native and European societies at the time, Columbus exacted a tribute from the vanquished tribes, requiring what he considered to be small quantities of gold from those who had access to it and cotton from those who did not, and meting out moderate punishments to those who didn’t meet their quotas. The natives initially agreed to the terms, but when the gold quota proved too high, Columbus halved it.

Columbus continued his assault on Caonabó and his allies until the native king was captured, after which an uneasy peace descended upon the island. But Columbus’ dream of a utopian world in which natives and Europeans worked in harmony to draw riches from the earth lay in ruin.

Instead, most of his resources were poured into building forts, patrolling the island and collecting tributes from tribes that were primed at any moment to erupt into violence. All efforts to convert the natives to Christianity were abandoned. At that point, they so hated the Spaniards that any such attempt would have been futile.

While touring the island after the capture of Caonabó, Columbus discovered widespread famine triggered by the decision of many of the chiefs to compel their tribes to tear up their own crops in a misguided attempt to starve out the settlers.

In two short years, Columbus’ letters to the king and queen had devolved from joyous celebrations of the vast potential of his endeavors to plaintive efforts to explain the lack of gold production, justify the vast expense of the enterprise and seek reassurances that he still held their favor. Reading between the lines of those letters and judging by the outcomes of his trips back to Spain, he was on firm footing with the crown.

With supplies running desperately low, Columbus left his brothers in charge of the island and returned to Spain, bringing Caonabó and a couple dozen of his tribesmen with him to stand trial. He was also intent on combating the criticisms that had flowed across the Atlantic in the previous months. Caonabó perished during the crossing. With the ships approaching Spain and the larders nearly empty, the crew proposed eating the remaining natives or throwing them overboard, but Columbus refused to permit either.

Hearing Columbus’ side of the story upon his return to Spain, the king and queen renewed their commitment to him. They authorized the release of supply ships to return to Hispaniola directly, giving Columbus additional vessels to continue his search for the continent. But his first two voyages had drained the royal treasury, simultaneously ruining his once stellar reputation and earning him bitter enemies in the court.

As a result, the launch of his supply ships was delayed a full year, and his own expedition didn’t depart until 10 months after that. Because funds were so scarce, Columbus was forced to swell the ranks of his crew with felons who were offered their freedom in exchange for a period of free labor working the gold mines.

Columbus was finally able to make landfall on the continent, but during his explorations, the supply ships were still wandering the Atlantic. Both groups of vessels arrived at Hispaniola at around the same time to find the island consumed by chaos.

With starvation and dissatisfaction running rampant among Columbus’ men, one of his administrators, Francisco Roldán, led many of them in revolt, plotting to kill Columbus’ brothers. When that failed, they seized control of a portion of the island.

Outnumbered, outflanked and facing possible death at the hands of the insurrectionists, Columbus was forced to accept a series of humiliating capitulations that included giving Roldán and his men control of plots of land and the natives who lived on them.

Before inking the deal, Columbus warned the affected chiefs, who agreed to play along in exchange for the elimination of the tributes. Forewarned, many of them were able to escape the island. The rest were roundly abused by Roldán.

Columbus sent a desperate letter to the king and queen, asking them to deliver troops to restore order to the island, but there was no immediate response. He also sent some of Roldán’s slaves back to Spain as evidence of the sorts of abuses being committed against them. A secret letter of explanation was also sent but never arrived, prompting the queen to assume the slaves were Columbus’ doing.

Columbus was finally wrestling the island under control, severely punishing the insurrectionists as well as those who abused the natives, when a dark force swept him from his position, dooming the indigenous populations to a swift extinction.

Inundated with malicious tales of Columbus’ mismanagement and cruelty, the king and queen sent court official Francisco de Bobadilla to gather findings and report back. Upon his arrival, he unceremoniously stripped Columbus of his power and property, imprisoned him without taking his testimony, gathered a host of outlandish accusations against him and sent him back to Spain in chains along with his report. Bobadilla remained on as governor.

It didn’t take long for the king and queen to sniff out the truth and exonerate Columbus. They restored his property and privileges but removed him from the governorship, authorizing him to explore the outlying islands instead.

Meanwhile, Bobadilla was giving his men license to enslave, rape and murder the natives and subject them to forced labor. Catching wind of these transgressions, the king and queen sent a team led by Nicolás de Ovando to remove Bobadilla from power, punish the offenders and restore relations with the native populations.

As awful as the abuses were under Bobadilla, the real reign of terror commenced when Ovando took control of the island. Columbus himself delivered a heartbreaking account of those atrocities and their consequences in a letter he wrote to the king during his fourth voyage.

“I am informed that since I left this island six parts out of seven of the natives are dead; all through ill-treatment and inhumanity; some by the sword, others by blows and cruel usage, others through hunger. The greater part have perished in the mountains and glens, whither they had fled, from not being able to support the labor imposed upon them.”

By the time Columbus returned from his fourth voyage, his spirits, health and reputation were shattered. The queen passed away a few weeks later, and Columbus spent the remainder of his days embroiled in legal battles aimed at forcing the king to live up to the promises he had made. Columbus died an utterly broken man a year and a half later.

To counter the critics, click here.

The above appears in the October 2022 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Mille grazie to Rafael Ortiz, author of “Christopher Columbus The Hero,” for setting me on the path to discovering the real Christopher Columbus, and to Chicago-area attorney Michael A. Benedetto for inspiring me to dig deeper.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

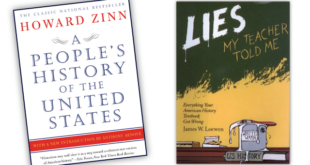

Great synopsis! I have been studying the “Columbus question” for two years. This article gives clear insight. I recommend Mary Grabar’s “Debunking Howard Zinn.” She traces political and educational movements since WWI.