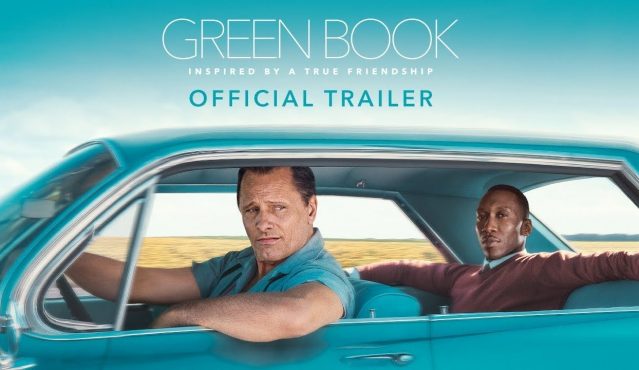

I can’t recall the last time a film was as simultaneously popular and polarizing as “Green Book.”

The story about the unlikely friendship that blossoms between a casually racist Italian-American bouncer and an elitist African-American concert pianist during a road trip through the South in 1962 was a fan favorite, earning $322 million at the worldwide box office. It also cleaned up during awards season, netting Oscars as well as Golden Globes for best picture, supporting actor and original screenplay.

But the cinematic rendition of the real-life sojourn taken by Frank “Tony Lip” Vallelonga and Don Shirley attracted as much controversy as it did acclaim. Some critics pigeonholed it as a white savior film and others as the exact opposite. Shirley’s family decried his portrayal as a “symphony of lies,” and on the facing page of this issue, activist Bill Dal Cerro takes the film to task for its shopworn depiction of Italian Americans as either buffoons or gangsters.

My take on the film is rooted in the assurances offered by Vallelonga’s son, Nick, who co-wrote the script based on extensive conversations with his father and Shirley, who remained friends until they passed away within months of each other in 2013.

“I wanted the feelings to come from the truth because the story is so amazing that the truth is enough,” he told Time magazine. “I felt that we could not make up a scene in this movie.”

If we’re to take him at his word, much of the criticism evaporates and we’re free to judge the movie by other standards.

When it comes to the film’s portrayal of Italian Americans, I wholeheartedly agree with Bill that our community’s proud legacy of civil rights activism has been largely ignored by Hollywood. But I don’t think that negates the importance of telling the “Green Book” story, and I don’t think the story reflects poorly on us at all.

Yes, Vallelonga and his family are portrayed as racists at the start of the film, but by the standards of the era, they’re easily the least racist whites in America. While blacks across the South were being routinely beaten for drinking from the wrong fountain, the worst crime the Vallelongas commit is sending a handful of male relatives over to “watch the baseball game” while watching over Tony Lip’s wife when a pair of African-American plumbers show up to work on the sink.

Yes, Vallelonga operates on the fringes of the mob, but when they offer to pay him handsomely to do their dirty work, he chooses the path far less travelled, honoring his commitment to escort a black musician for far less money on a risk-fraught odyssey.

Yes, Vallelonga is portrayed as undereducated and unrefined, but he has loads of street smarts and he’s completely comfortable in his own skin, never once bowing to the expectations of polite society.

And yes, Vallelonga is quick to anger, preferring to resolve conflicts with his fists rather than his words, but he’s also big-hearted, straight-shooting, laugh-out-loud, fiercely loyal and deeply principled, emerging as the moral center of the film.

When emissaries from New York arrive halfway through the tour to tempt him back home with the promise of more money, he stands by Shirley, also refusing the musician’s counteroffer of a raise and promotion because that wasn’t the original deal.

After Shirley has a particularly rough night, Vallelonga opts to share a room with him in a fleabag segregated hotel rather than abandoning his new friend to his sorrows.

And in a rousing climactic scene, he delivers an impassioned working-class manifesto that strips Shirley of his privileged veneer and reveals the tortured soul within.

The two arrive in New York at the end of the film on Christmas Eve, seeming to go their separate ways. At a festive dinner with his family, Vallelonga puts his foot down at the first hint of racism and everyone at the table immediately falls into line. And when Shirley unexpectedly shows up, the entire family welcomes him with open arms.

Now THAT’S Italian. And that’s why I loved “Green Book,” whatever its flaws may be.

The above appears in the November 2019 issue of the print version of Fra Noi. Our gorgeous, monthly magazine contains a veritable feast of news and views, profiles and features, entertainment and culture. To subscribe, click here.

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian

Fra Noi Embrace Your Inner Italian